In Philly galleries, three must-see shows for December

Matthias Schaller's photos of artists' palettes, Kukuli Velarde's frank feminism, and a crowd-sourced show at Penn

When German photographer Matthias Schaller paid a visit to Cy Twombly’s studio in Gaeta, Italy, in 2007, he noted the resemblance of one of the painter’s palettes to his paintings.

Schaller has a detective’s instinct for the meanings of things left behind and the feelings they arouse. He had documented empty studios of photographers and architects, unoccupied work spaces of cardinals at the Vatican, and early astronaut suits.

And in that Twombly palette, he recognized his next project.

He was soon shooting a Who’s Who of artists’ palettes. Now, 27 of those large-format color photographs are on view at the Berman Museum.

That exhibition, “Die Meisterstuck” (The Masterpiece), is an impressive effort even by Berman standards. The series, then nascent, made its debut in 2010 at the Kunstmuseum Picasso in Muenster, Germany. Five years later, 20 of the photographs were displayed during the Venice Biennale.

Almost all of the palettes are the classic flat, wooden kind, and Schaller photographed them vertically, thumb hole at top.

All belonged to prominent painters of the 19th and 20th centuries and were found by Schaller in museums, foundations, and private collections.

At first glance, I was disappointed that the palettes were not more like their respective artists’ paintings.

The only ones immediately identifiable were Van Gogh’s, with its thick, heavy strokes of green, yellow, and orange paint; Miro’s, with cheerful blobs of red, yellow, blue, and white; Chagall’s, like a mini version of one of his paintings; and Twombly’s, with its energetic strokes and smears.

A longer, closer look was rewarding, though. Morandi’s atmospheric blur of a palette — a complete anomaly in this group — matches the pale backgrounds in his tabletop still lifes.

Eugene Delacroix’s palette, another outlier, is daubed with premixed colors arranged in rows. It reveals him developing his color scheme for a particular painting. (He went through numerous palettes and liked to show them off to visitors).

The crusty bits of yellow and white confined to a corner of Renoir’s palette suggest he had an inner Twombly itching to break loose, as do some anxious zigzag strokes in the center. In fact, a number of palettes seem to reveal avant-garde urges not realized in paintings.

I’m still curious about the palettes that seemed least likely to belong to their artists -- Kahlo, Gauguin, Manet, Monet, Matisse, and de Chirico, among others.

Was it simply a matter of thriftiness and using palettes longer than the others did? Or were these painters so absorbed in their visions that the palette was peripheral?

I’d guess the latter.

Through Dec. 19 at the Berman Museum, Ursinus College, 610 E. Main St., Collegeville, 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays through Sundays, 610-409-3500 or ursinus.edu.

Frank feminism at Taller Puertorriqueño

Kukuli Velarde, a Peruvian-born Philadelphia artist, is known primarily for her feminist ceramic reinterpretations of pre-Columbian sculptures.

The recipient of a Pew Fellowship and a Guggenheim Fellowship, she is now having her first Philadelphia solo show of paintings, at Taller Puertorriqueno.

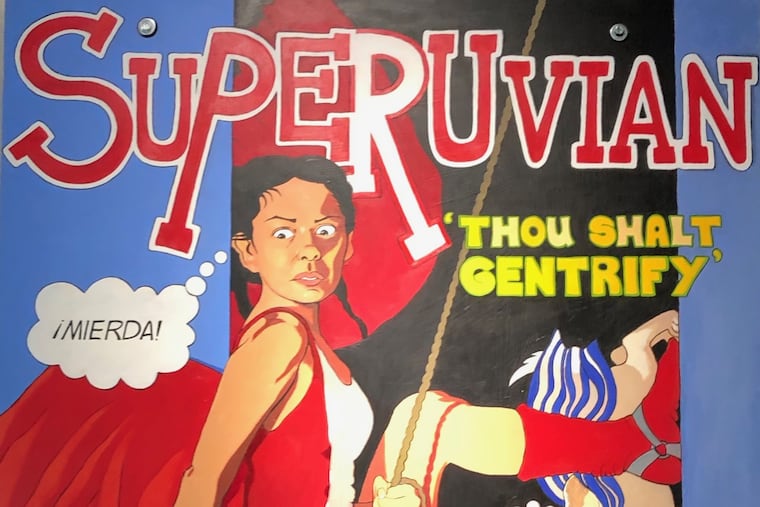

“The Complicit Eye” features paintings from 2005 to the present, all of which depict Velarde as the central character in narratives critiquing stereotypical women’s roles. There’s the pin-up girl, the comic book superhero, the goddess, the everyday sex object.

Velarde’s large paintings on aluminum borrow the scale and look of 16th-century Latin American religious paintings, and of the Mexican murals by the all-male roster of Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros, and others.

Interestingly, though her works depict Velarde in mostly degrading situations, you sense she’s in control of her destiny.

My first thought on seeing these paintings was that Velarde was channeling Kahlo, but her paintings aren’t uncomfortably personal or narcissistic. They’re disturbing and outspoken.

Through April 30, , at Taller Puertorriqueño, 2600 N. Fifth St., 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Mondays through Saturdays. 215-426-3311 or tallerpr.org.

Crowdsourced show at Penn

Last spring, Heather Gibson Moqtaderi, an assistant director and associate curator at the University of Pennsylvania’s Arthur Ross Gallery, asked members of Philadelphia’s art community to vote online for their favorite works in the university’s art collection.

Now, the chosen works are on display in the gallery’s “Citizen Salon” exhibition, accompanied by observations from some of the choosers. It’s a curious display of great works and forgettable ones. (Full disclosure: I voted for a Hobson Pittman painting that made the cut.)

The stars are paintings, including March Avery’s Karla & Nicholas (much in her father, Milton Avery’s, style), Humbert Howard’s Folk Festival Gathering, and Henry Inman’s Rydal Mount, accompanied by a comment from Kathleen Foster, the Philadelphia Museum of Art curator of American art.

Pittman’s painting Music Room at Strawberry Mansion is perfectly described by Jim Hartman, a local art collector and dedicated volunteer at the musuem: “Pittman mastered the ability to paint room and indoor scenes where the viewer is pretty sure an ethereal character is in the scene. The thrill of seeing a ghost in just about every one of these interior scenes has not been duplicated.”

I’m with Jim.

Through March 24 at Arthur Ross Gallery, Fisher Fine Arts Library Building, University of Pennsylvania, 220 S. 34th St., 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays, Thursdays, Fridays; 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Wednesdays, noon to 5 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays, 215-898-2083 or arthurrossgallery.org