Under Trump, science isn’t dead. Feds’ new focus includes AI, quantum computing.

Despite early skepticism from critics, the Trump administration has announced a series of measures that are expected to strengthen science and research.

President Donald Trump’s famous skepticism toward the Paris Agreement air pollution reduction deal and “green energy” subsidies, and his penchant for putting fossil-fuel executives in charge of environmental policy, left liberals fearing that his administration would prove “unprecedented in its violations of scientific integrity.”

Those fears were fed by a 2017 CBS News story that the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy had been gutted to just 35 people, down from more than 100 under President Barack Obama.

Worries among serious scientists receded a bit after Trump nominated meteorologist Kelvin Droegemeier to run the office last year. Staffing is back up to 60, where it was under President George W. Bush, according to office veterans who spoke on condition of anonymity.

And, as under prior presidents, Trump appointees have made their mark on policy.

In February, Trump signed an executive order to launch the American AI Initiative to prioritize government science spending toward artificial intelligence, speed AI development through new reliability and safety standards, and somehow balance “open markets” to import AI tech — while securing our own against foreign spies.

Trump science staffers say they have identified $5 billion in defense and nondefense AI spending this year — up from $1 billion under Obama, according to a 2015 inventory.

The AI push was followed in May by a more preliminary “National Quantum Initiative Act.” The new law offered federal grants to develop a handful of academic R&D centers into so-far-hazy new computing technologies to develop machines using principles from quantum mechanics, instead of the familiar binary electronic computers.

The first $31 million in the new federal quantum R&D research funding was assigned in September, including a total of $1.5 million split between two scholar teams led by Lee Bassett and Liang Feng at the University of Pennsylvania.

White House science leaders say they are also reviewing the next initiatives in 5G fast internet, self-driving cars, commercial drones, and civilian supersonic aircraft.

Besides those science targets, the office under Droegemeier is trying to address the perception that too much is spent on research that is of marginal practical value, and concerns that valuable U.S. insights and innovations are routinely stolen and used by government industries in China and other countries. His office is also making sure that women, foreign-born students, and other groups don’t face unnecessary added burdens because of who they are, and reducing administrative complexity in an environment where paperwork requirements already eat up nearly half of academic researchers’ work time.

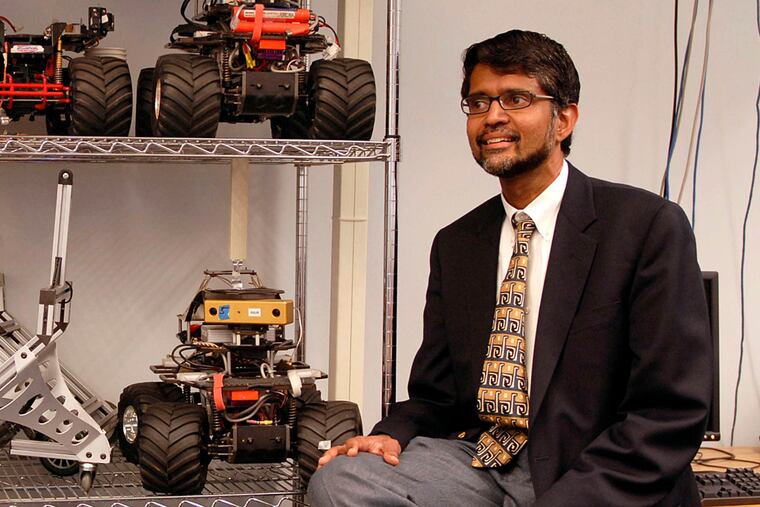

Vijay Kumar, dean of engineering at Penn, worked at the Office of Science and Technology Policy in 2012-14 and considered the time valuable in connecting to National Institutes of Health, Pentagon, and other federal research funding leaders — very useful for a future engineering school dean.

“The mission is very broadly speaking about two things: promoting science and technology, to enable better policy-making, and promoting policy, to enable better science and technology,” Kumar told me in a recent interview.

Kumar praised the office’s AI initiative.

“This administration is focused on jobs for Americans today. The administration believes the threat is real, that other countries are going to beat us. They see AI as transformational, that every job going forward will be transformed by AI,” he said.

Kumar would like to see similar efforts brought to bear on long-term science infrastructure — including immigration initiatives to ensure the future supply of scientists and engineers, a set of problems he said was studied but not sufficiently addressed by the Obama administration.

Are you running out of U.S.-born students at Penn Engineering, I asked Kumar. He said interest is high from both U.S. and foreign students — so high that adding undergraduate computer classes is like building highways in the suburbs: “When we double the classes, we also double the waiting lists.”

But recruiters report that foreign students, an important supply for most engineering schools, are starting to wonder if they are still welcome here and if they will be able to pursue opportunities in the United States after graduating, Kumar added.

“Steve Jobs’ father was Syrian; Sergey Brin [cofounder of Google] came from a Russian family; the CEO of Alphabet [Google’s parent company], Sundar Pichai, is an Indian immigrant. Would they get visas today?”

So Penn has made computer-based programs online and universal — such as its master’s of computer information technology, popular among tech company employees.

“We take 70 students in the campus program,” Kumar said. “But we now have about 450 enrolled online and expect 300 more in January. This is a tenfold increase in our capacity.” How is he marketing, to find so many students? “We haven’t marketed to anyone yet. The reputation of the institution, the quality of the instruction, speaks for itself. But we will be more strategic.” He hopes Washington will also.