Can states go bankrupt? Here’s how Puerto Rico did, with a Penn Law prof’s guidance.

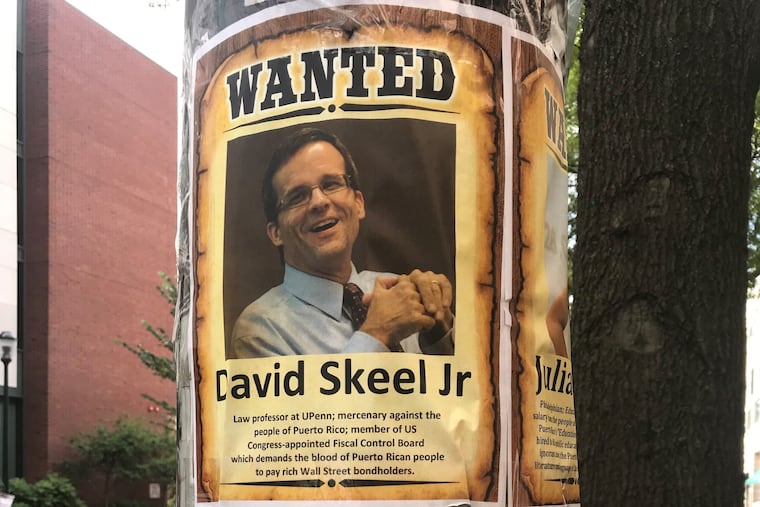

Penn Law's David S. Skeel tells how he made bondholders and patriots mad at him while heading the board that made the "largest public debt restructuring in American history."

When squabbling politicians fail to provide effective public services, and spend all the people’s money, it can be tempting to wish a giant hand would reach down and make everything right.

That’s what Congress has tried to do over the past six years in Puerto Rico, a state-sized U.S. colony with twice the population of Philadelphia. A Penn law school bankruptcy professor, David S. Skeel, headed the effort for most of its existence, climaxing in January with the plan’s approval by federal Judge Laura Taylor Swain.

Under U.S. law, individuals, businesses, and even cities can go bankrupt, but states and colonies cannot. So what’s happened in Puerto Rico is a blueprint for what could happen as aging U.S. states, such as New Jersey and Pennsylvania, continue to spend money they don’t have.

In 2015, Puerto Rico owed Wall Street investors $72 billion, which then-Gov. Alejandro García Padilla said the island could not pay. It also faced a pension deficit of over $50 billion — almost as large as Pennsylvania’s, for a population less than one-fourth its size.

So Congress in 2016 approved the oversight board, known locally as la Junta, comprising a small group of businessmen, financiers, and scholars. It was appointed by President Barack Obama and his successors to restructure Puerto Rico’s debt, taxes, and spending after elected leaders couldn’t agree on a working plan. Natalie Jaresko, the American-born former Ukraine finance minister, is its paid executive director.

The board demanded cuts and delays for Puerto Rico’s debts it said should never have been approved under the island’s laws. It pushed for asset sales to raise cash, spending cuts to avoid going broke, and sought to replace unfunded pensions with private-sector-style savings plans.

Its members were aggressively criticized by leftists and labor leaders who saw these “traitors” as selling out the fatherland and by Wall Street “vulture” investors who demanded full repayment even on high-risk bonds they had bought at deep discounts.

The plan’s approval followed long delays for ruinous hurricanes and the pandemic. The board said the plan “reduces the debt by 80% and saved Puerto Rico more than $50 billion” in long-term payments, adding that Puerto Rico can now move on “from financial instability and insolvency to a future of opportunity and growth.”

Skeel’s books include Debt’s Dominion, which argues U.S. bankruptcy laws helped speed the nation to prosperity. He says his work is informed by his faith as an evangelical Christian. His Wall Street Journal essay last year cited biblical precedent for reducing Puerto Rico’s debt while ensuring one pays the debts one can.

Skeel recently answered questions about the plan. This interview is edited for clarity and brevity.

The U.S. Bankruptcy Code lets cities reorganize, but not states. Is this a one-of-a-kind deal or a model states might follow?

This is the largest public debt restructuring in American history. When we are at the point where folks are talking seriously about bankruptcy for states, this will be the touchstone.

I’ve been a big advocate of bankruptcy for states. This has been sobering. It took a long time. This has given me a better sense of how complicated the balance sheet is for a public entity that has a very complicated set of constituencies for whom it is providing goods and services.

And now I’m pretty optimistic. I think it’s a great deal for Puerto Rico and a completely fair deal for the creditors. Puerto Rico’s population is rising again [to an estimated 3.3 million in 2021, from 3.2 million in 2019].

What did the judge finally approve?

We settled the general obligation bonds, the biggest part of the debt, at 85 cents to 90 cents [payback to investors for every dollar borrowed]. The rates are fixed [so the Fed’s interest rate hikes will have limited effect].

We converted the Employee Retirement System [to a private-sector-style savings plan, without the taxpayer guarantees]. We froze the pension [for people still working]. Those vested will get that money.

Retirees and beneficiaries have no cuts at all, Gov. [Pedro] Pierluisi insisted on that. There was a freeze on pension cost-of-living increases.

There were $3 billion in pension bonds. They will get a lower payout than the investors wanted. They litigated with us, and we won.

Pension managers had used that borrowed money to buy private equity investments that did poorly?

I hope there’s never another time they borrow. The pension bondholders get 20 cents on the dollar.

But you still have that $50 billion legacy pension deficit. How are you going to pay that?

We set up a pension trust to set aside money. The government is required to pay in at least $175 million a year.

The unions resisted the pension freeze; the last three governors urged them to fight you on that, no?

We made a deal with the American Federation of Teachers, but the locals voted down the plan. It went to court. [On April 26, the First Circuit Court of Appeals ruled for the board.]

What keeps future governments, with all the pressure they face, from again spending more than they collect?

One cool thing in the plan is a 10-year debt management policy. There are limits on how much they can borrow, and limits on interest rates, and it has to be used for capital improvements [not new hires or other operating costs].

What did you most insist on?

The thing that mattered to me most was how much debt responsibility Puerto Rico would have going forward. We drew a line in the sand at $1.15 billion a year. I said we are not going higher than that.

And it turned out there was more cash than some of us had expected because Puerto Rico hadn’t been paying debt for five years, and the tax money and the federal disaster money started accumulating.

And we added a “contingent value instrument” (CVI) keyed to sales tax revenues. In Puerto Rico, the sales tax is high, about 11%. Almost half of that is set aside to pay creditors. But if they collect more sales tax than we projected, some [of the increase] will go to pay more debt.

There is very limited debt going forward, compared to what it was. The bondholders get a good payback. The clawback [for bond insurers] is not as good.

What about PREPA, the power company?

PREPA has not been settled yet. We’re doing that. The government has brought in a private transmission and distribution operator [LUMA Energy, owned by Quanta Services of Houston and Canada-based ATCO]. They had outages after they came in last summer and complaints. Things are getting better.

Will the island switch away from expensive imported fuel?

They have put out a request-for-proposals [to replace] the existing generation operations and to bring renewables online. There is a governmental policy to be 100% renewables by 2035.