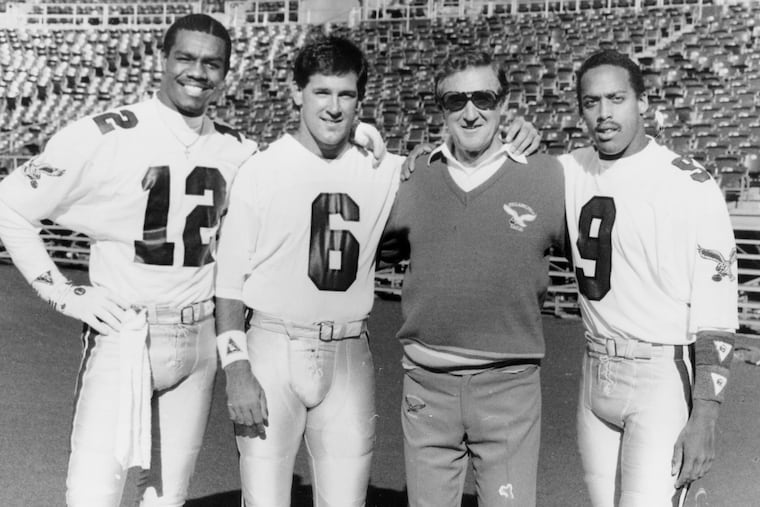

Doug Scovil was the guru who developed Randall Cunningham. His influence was even greater on another Eagles QB.

Doug Scovil treated rookie Don McPherson like a QB, not just an athlete. It stuck with McPherson his whole life. Scovil died of a heart attack before an Eagles game in 1989.

One in an occasional series. The Eagles will wear throwback kelly green uniforms for the second time this season in Sunday’s game against the Bills. These are some essential stories from the Birds’ kelly green era.

Before the Eagles selected him in the sixth round of the 1988 NFL draft, Don McPherson dared to send a letter to every team in the league, a letter with a demand: Don’t pick me unless you plan to play me at quarterback. McPherson had just led Syracuse to an unbeaten season, finished second in the Heisman Trophy voting, and won the Maxwell Award as the college football player of the year. But he knew that the reflexive racism throughout the NFL threatened to pigeonhole him. Chances were good that he’d end up with a coach who would move him to wide receiver or running back or another position that Black players were considered properly equipped to play.

McPherson would have been forgiven for fearing, before meeting him, that Doug Scovil might fit that stereotype of a close-minded authoritarian. Buddy Ryan had hired Scovil in 1986 as the Eagles’ quarterbacks coach, charging him with shaping Randall Cunningham — gifted, raw, and often immature — into a polished passer. Now McPherson would be under Scovil’s tutelage, too. How rigid would Scovil be in his instruction? McPherson likely would be the Eagles’ third-string quarterback, behind Cunningham and Matt Cavanaugh, and he had fallen so far in the draft in part because his official height, 6-foot-1, marked him as too short to be any good in the NFL. Would Scovil even think him worth his time?

McPherson’s concerns were an insignificant subplot then for the Eagles and those who followed them. Cunningham was the franchise quarterback and Scovil’s primary pupil. Their tight relationship and Cunningham’s improvement over his first three years as a full-time starter were a source of hope that the Eagles could get back to the Super Bowl for the first time since 1981 and, this time, win it. That dream faded to a distant afterthought once Scovil died at 62 of a heart attack at Veterans Stadium in December 1989, 24 hours before the Eagles hosted the Dallas Cowboys there.

» READ MORE: Before ‘Black Hawk Down,’ Mark Bowden covered the Eagles like no one else

The shock and sadness of the tragedy stretched beyond Scovil’s family, beyond the horrible reality that his wife, Enid, had lost her husband and their three children had lost their father. It stretched to the Eagles’ coaches and players, who liked the good-natured, avuncular quarterback guru. It stretched to Cunningham, who regarded Scovil as a father figure. And it stretches still to McPherson, who has since forged a career as an author and speaker and whose voice started to crack when he was asked about Scovil in a recent phone interview.

“You actually gave me goosebumps,” he said. “He was a special guy to me. I’m getting emotional right now.”

Project Randall and the pitch count

Scovil had volleyed between college football and the NFL since the early 1960s. He and Ryan had met in 1978, when the former was the Chicago Bears’ defensive coordinator and the latter was their wide receivers coach. For Scovil, that season was the single slice of lunch meat in a football Wonder Bread sandwich: In 1976 and ‘77, then again in ‘79 and ‘80, he was the offensive coordinator and quarterbacks coach at BYU.

“You can’t find a whiter place in the country,” McPherson said.

There was no ambiguity about Scovil’s mission with the Eagles. They had drafted Cunningham in the second round in 1985, the dawn of the team’s kelly green era, and for all his arm strength and speed, he still needed someone to help him refine the ragged edges of his game: shorten his elongated, whiplike throwing motion; teach him to read defenses; help him understand when to scramble and when to hang in the pocket. From 1982 through 1984, while Cunningham was UNLV’s quarterback and punter, Scovil had been the head coach at San Diego State. The teams had faced each other three times during that period.

“He was very impressed even then with Randall’s athleticism and potential as a quarterback,” Scovil’s son, Randy, said. “He came in knowing that Randall might have been put out there too early his rookie year and wanted to give him a good foundation and the means to succeed. It was pretty clear, not long after, that they were on the same page.”

Roger Staubach at Navy, John Brodie with the 49ers, Jim McMahon at BYU: Scovil had coaxed excellence from those quarterbacks and more in his career. “He always had a great ability to connect with people from all backgrounds,” Randy said. “He seemed to have a good sense of how he could help and motivate people. He kept things low-key when possible to keep things calm and focused.”

» READ MORE: Jalen Hurts takes pride in being the next in the Eagles' legacy of Black quarterbacks

Project Randall promised to be a new and different challenge. Among the quarterbacks Scovil had tutored, only McMahon had exhibited anything close to the renegade mindset of the cocky, bleep-talking team that Ryan was building in Philadelphia. And Cunningham sometimes appeared less interested in his preparation and playbook than in the trappings of NFL stardom — the fame, the endorsements, the hobnobbing with celebrities.

“We had a lot of guys who were Buddy-type guys, and Randall was that way, too,” McPherson said. “Talked a lot. Joked a lot. Buddy brought in a lot of young, brash guys. I was one of them. I was considered Buddy’s pick. I was outspoken. We had guys like Jerome Brown, Seth Joyner. Doug was unflappable in the face of all that. He was steady. He took no mess from Randall.”

» READ MORE: Wes Hopkins punished receivers for the Eagles’ great kelly green defenses. Life returned the favor.

Cunningham evolved into the league’s most breathtaking player — the “ultimate weapon,” as a Sports Illustrated cover called him — and credited Scovil for it. “He has turned me around,” he said weeks before Scovil’s death. “My first year, I wasn’t ready to play, but working with Doug Scovil in the offseason, it’s helped me so much. Now I feel confident. Doug stays on my case and keeps my head down instead of being all proud and everything. He keeps me down to earth.” The residue of Scovil’s influence on him apparently lasted for another year: Cunningham had his best season with the Eagles in 1990 — his first season after Scovil died — throwing 30 touchdown passes and rushing for 942 yards.

While the media and public fixated on his work with Cunningham, though, Scovil spent as much time or more with McPherson. “Doug was the first coach who said, ‘Forget all that stuff. Forget everything that people said about you. Forget the hype of who you were as a college quarterback,’ ” McPherson said. “The knock on me, that I was too short, Doug told me, ‘Look, I coached Steve Young. I coached Jim McMahon. You’re just as tall as both of those guys. Put all that stuff out of your head, and let’s just focus on being a better quarterback.’ ”

One day early in his rookie season, McPherson was quarterbacking the scout-team offense at practice. He had a card that listed all the plays he was supposed to run, and, by rote, he was calling and carrying out each one in sequence. After one play, Scovil pulled him aside.

“Why would you throw that ball?” Scovil asked.

“Well,” McPherson said, “it’s what’s on the card.”

“You think if Joe Montana saw that coverage,” Scovil said, “he would throw the ball there?”

“No, I guess you’re right.”

“So if you see that coverage, don’t throw what’s on the card. That’s not what Montana’s going to do. That’s not what Dan Marino’s going to do. They’re going to throw it where the defense dictates.”

The following year, during a training camp workout, Scovil told McPherson, You’re not throwing the ball tomorrow. You don’t throw one pass all day. If it’s a pass play, drop the ball in the dirt. Then he explained why: Ryan’s two-a-day practice schedule, in Scovil’s mind, wasn’t giving McPherson enough time to rest his arm. Ryan couldn’t understand it. This kid’s trying to make the team again, and you’re telling him not to throw the ball? But Scovil stood firm. He had McPherson on a pitch count to protect him from an injury or a poor performance.

That gesture, and Scovil’s reason for it, stuck with McPherson. It made him understand how little instruction in the fundamentals and intricacies of the position he’d actually received in high school and college. All his career, he had been treated like an athlete at best and a commodity at worst, not like a quarterback.

“That’s the part that made me feel really special,” he said. “In the madness of practice, in the madness of training camp, I had this really calm, deliberate coach who was helping me get better. I’d never had that before.”

» READ MORE: Ranking the 50 greatest Eagles players of all time

The most hated game

A native of northern California, Scovil was easygoing, with an impish smile and gray-blond hair that covered his ears. Away from the field, he’d talk chardonnay and pinot — “He was a wine guy,” McPherson said — and it was common for him, after practices and on off-days, to exercise with the Eagles’ players in the team’s training facility. Just after noon on Saturday, Dec. 9, 1989, he was pedaling on a stationary bike in the cardio room.

In the weight room next door was David Little, a backup tight end. Little was particularly diligent about working out; he felt he had to stay in peak physical shape to retain his roster spot. “I always seemed to be the last one out,” he said by phone, “and Doug seemed to be there, too.” Every day, he’d turn off the lights in the weight room; check in with David Price, the Eagles’ assistant trainer; then say goodbye to Scovil.

True to his routine, Little walked into the cardio room to see Scovil. He found him lying on the floor. He called out to Price: “Dude! Come over here! Hurry up!” Price checked Scovil for a pulse and started CPR on him while Little called 9-1-1. Scovil was pronounced dead at 1:04 p.m.

Little is 62, the same age that Scovil was when he died, and he himself suffered a massive heart attack last summer. “My thoughts went directly to Doug,” he said. “I think about it all the time.”

So does McPherson. The day following Scovil’s death remains among the most infamous in Eagles history. They beat the Cowboys at the Vet, 20-10, but their fans dumped beer and chucked ice and snow at Dallas coach Jimmy Johnson and his players. In the 600 level, Ed Rendell, formerly the city’s district attorney, less than two years away from being elected mayor, bet a fan $20 that the fan couldn’t throw a snowball far enough to reach the field. The guy nearly hit the back judge.

The Eagles played the game with black tape stripped across the wings on their helmets, to honor Scovil. Instead of standing on the sideline with his teammates, McPherson spent that game in the coaching booth, in Scovil’s seat, wearing Scovil’s headset, communicating with offensive coordinator Ted Plumb.

“I don’t know that I’ve ever hated a game more than that one,” he said. “I felt lost, just lost without him. It was one of the first times in my life as a football player that I felt like I had no idea what I was doing.

“He was the closest person to me in my life at that point who had died. I was his last protégé. I was his last project. I was with him almost every day for a year and a half before his passing. In some small way, it made me feel a little more special that I was his last guy. He meant a lot to me. He really did.”

Just before he hung up the phone, McPherson started to rummage through his office desk. A few seconds passed. “I have it in my hand now,” he said. Then he revealed what he had been looking for. He was holding a palm that had been bent and shaped into a cross. Everyone who had attended Doug Scovil’s funeral, nearly 34 years ago now, had received one. Don McPherson had kept his.