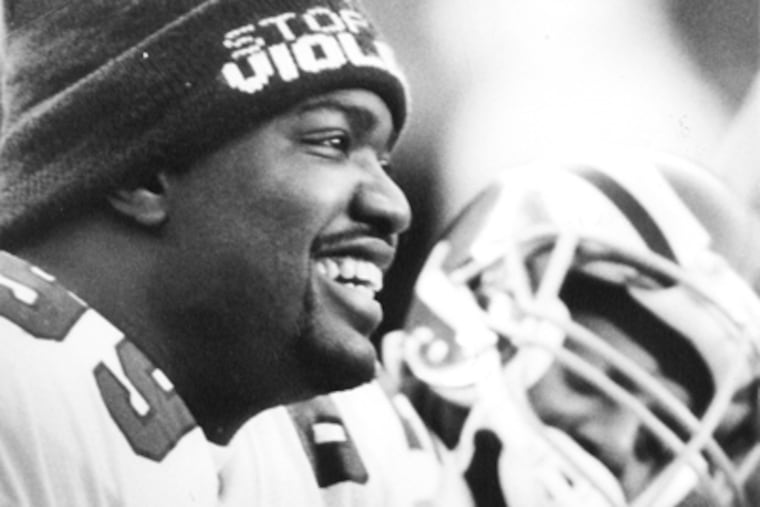

Jerome Brown has been gone for 30 years, but his joy endures for this former Inquirer Eagles writer

Everybody had a Jerome Brown story. Here's my favorite that showed how he always tried to make football fun.

Suddenly and inexplicably enraged, Jerome Brown sprang from his seat, wrapped his thick arms around me and lugged me like a rolled-up rug to the other side of the Eagles’ locker room. I thought for a second there that I’d wind up in a trash can, legs up.

I’d made the mistake of being the first reporter to approach Brown at lunchtime and ask a question. I don’t remember what I asked, but I am sure it was just an icebreaker. Brown, a very large man hunched in a very tiny stall, looked up at me. No, wait. He glowered at me.

» READ MORE: The 50 greatest Eagles players of all time

Then he detonated. “... damn it!” he shrieked. He picked up a stool with an Eagles logo, and chucked it across the room, bouncing it end over end. Then, in one swift motion, he effortlessly picked me up, as if I were a tackling dummy.

As sportswriters and his puzzled teammates looked on, Brown hauled me to the entrance to the showers … but then, just as adeptly, gracefully set me back down on my feet and kept his arms around me until he knew I had my balance.

He looked at me, winked, then whispered, “You know I have to give you a hard time.”

We laughed. Then we joined the reporters at his locker, and we asked all the questions we wanted. This was in 1991, way back in the days when confrontations between athletes and reporters sometimes got physical, often not in a nice way.

But this was Jerome Brown. It was an act, an antic, something for a laugh, something to break up the routine. Brown made football fun, the way it should be. Everybody had a Jerome Brown story.

Larger than life, Brown was charming, hilarious, and profane — a treat to talk to, even about X’s and O’s. He was a magnificent football player, and I am certain that he would have made the Pro Football Hall of Fame had he not died in an auto accident in June 1992 at age 27.

» READ MORE: How we covered Jerome Brown’s tragic death, 30 years ago

He’d just had his finest NFL season. The 1991 Eagles lost quarterback Randall Cunningham to a season-ending knee injury in the opener, but the defense, coordinated by the late genius Leon H. “Bud” Carson, all but carried the hobbled Eagles into the playoffs.

That season, the Eagles had the NFL’s best defense against both the run and the pass, an NFL first in 16 years. Their front four — the ends Reggie White and Clyde Simmons, the tackles Mike Pitts and Brown, Mike Golic filling in — was dominant, menacing, and merciless.

These Eagles were a delight because none of them were the same. White, a licensed minister, was pious but relentless. Seth Joyner, the outside linebacker, was brooding and intense. Andre Waters, the strong safety, was emotional, rubbed raw. Eric Allen, the cornerback, was effervescent and efficient. Wes Hopkins, the free safety, was a clinical assassin.

Brown, No. 99 forever, added 300 pounds of jocularity. His timing was exquisite. Once, a group of reporters gathered after an Eagles loss around Joyner, always the go-to person for a ruthless critique. This gathering was suddenly disrupted by Brown, dancing naked in the background. He was hollering, “You watch what you say, Seth! They be writin’ it all down!”

Brown was up for any challenge. An October conversation about baseball that included running back Keith Byars became a discussion about pitching in the big leagues. A target was taped to a wall, and 60 feet, 6 inches was marked off to a strip of tape on the floor.

The players then realized they had no baseballs. So someone found a crate of oranges. Brown plucked out an orange and took his turn on the rubber. “Watch my sinker,” he said to all. His “sinker” totally missed the target, but the orange impressively splattered when it hit the wall.

» READ MORE: 5 Philly athletes who faced untimely deaths

Some things about Brown could not be explained at all. He took to carrying a leather briefcase to and from the locker room. (Someone later discovered it had nothing in it.) He reached into a heap in his locker after the 1991 season and pulled out a used casserole dish.

The last time I saw him alive was April 26, 1992, the last day of an Eagles minicamp. So much was expected of him that year. He made the Pro Bowl in 1990, but he bristled at being criticized for his work ethic. So he came back from a contract holdout in 1991 some 25 pounds lighter, and he had nine sacks to run his NFL total to 29½ in 76 games over five years.

This did not mean Brown had become serious. Brown noticed the rookie wide receiver Jeff Sydner getting dressed too quickly at his locker after the final minicamp workout.

“Hey!” Brown boomed. “He didn’t take a shower!”

The room got very quiet. Brown was on stage. He pointed to Fred Barnett, the fast wide receiver who always wore a sly grin.

“Hey! He’s one of yours!” Brown yelled at Barnett. “Get him to take a shower!”

Barnett looked at Brown, then looked over at Sydner. Halfheartedly, Barnett said to Sydner, “Hey. Take a shower.”

Arkansas Fred was apparently not stern enough for Brown. He marched into Otho Davis’ training room/hangout, which was known as “The Wildlife Sanctuary.” Brown came back out wearing a cowboy hat and brandishing a long whip.

» READ MORE: Hugh Douglas, Trent Cole to join Eagles Hall of Fame this season

“Eeeeeee-HAH!” Brown exclaimed, snapping the whip on a table in the center of the room.

Brown pointed the whip at Sydner and broke into song: “Rollin’, rollin’, rollin’, get those dogies rollin’, get those dogies rollin’, Rawhide!”

Those who were not singing were rolling on the floor, laughing. Lest it be said: Brown was a riot, but he was also a man who believed in cleanliness, if not necessarily Godliness.

I was assigned to cover his funeral in Brooksville, Fla., his hometown. It was on July 2, 1992, an oppressively sunny, hot, and humid day. There were so many mourners that the services had to be held at the First Baptist Church, the biggest in town. Its Sunday School building was used for overflow. Several people fainted.

It was heartbreaking to see Brown and his 13-year-old nephew, Gus, whom Brown merely wanted to take out for a joyride in his $60,000 Corvette that awful day, lying in state in open caskets. Brown did not look like himself. He was unrecognizable. He wore no smile.

About 20 Eagles attended the services. “He and myself were two kids in grown men’s bodies,” White had eulogized. A half-dozen players later dropped their silk ties on Brown’s coffin at his grave nearby. The gravestone is topped by an old Eagles logo.

White would be gone in 2004 at just age 43. Waters, who once told me, “I think I lost count at 15,” when I asked him how many concussions he’d suffered in his NFL career, died by suicide at age 44 in 2006 after developing chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Wes Hopkins died in 2018 at just 57, perhaps from CTE.

» READ MORE: 22 of the Eagles’ best playoff moments

Outside the church that muggy afternoon in Brooksville, Waters strolled over to a group of news reporters and said this about the service: “It was probably the most uplifting funeral I’ve ever been to — and I think Jerome would have wanted it to be like that.”

Waters then said of his departed teammate: “He was a joyous person — a person who always had a smile on his face, who always enjoyed life. If he’d had a choice, I think, he would have wanted to go out this way. Not being sad, but uplifting and joyous.”

Willie Jerome Brown III has been gone for 30 years now, but I can still see the wide smile on his face when he said to me, “You know I have to give you a hard time.” Unless you were with him on the field, though, his idea of a hard time was not really such a hard time at all.

Dave Caldwell lives in Manayunk. He grew up in Lancaster County, graduated from Temple, and covered the Eagles and other sports for The Inquirer from 1986 to 1995.