‘We can safely reopen schools’: In Philly school visit, U.S. education secretary vows help

“We’re at a point in our country’s history where every decision we make is either going to help address barriers in education, or worsen them,” U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona said.

U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona came to the Philadelphia region Tuesday, promising help from the Biden administration while urging school leaders to bring students back to classrooms.

“We need to offer students in-person learning options as quickly as possible, as safely as possible, so they can get back to the business of being students engaging with one another,” Cardona said at Beverly Hills Middle School in Upper Darby, where he toured classrooms with some students learning in person and virtually.

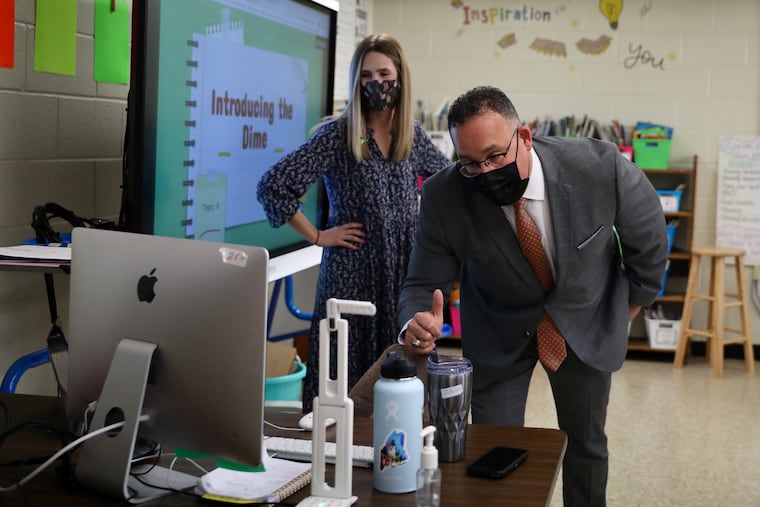

Earlier, he visited Jennifer Grunmeier’s second-grade classroom at Olney Elementary in Philadelphia, where seven students sat at desks with plastic dividers, backs straight against their chairs, while 22 others learning remotely were visible on a large screen at the front of the classroom.

“Guys, where are you? Turn your cameras on,” Grunmeier told a few students with cameras switched off. “We’re going to learn about earthquakes.”

Cardona elbow-bumped Grunmeier, nodding as she moved around her classroom. “It’s like magic, what you’re doing,” he told her.

His visit came after the Biden administration last month approved billions in federal relief money for schools — $1.2 billion for Philadelphia alone — and as its new education secretary tours schools to listen to teachers, parents, and school officials about their experience with education and COVID-19 reopening specifically.

“We’re at a point in our country’s history where every decision we make is either going to help address barriers in education or worsen them,” Cardona said during a roundtable with an Olney parent, teacher, and district staff.

“He’s been doing a great job with President Biden, getting more resources for our school,” Olney Elementary principal Michael Roth said when Cardona and Superintendent William R. Hite Jr. walked in.

» READ MORE: To honor Dr. King, fully fund Pa. schools, officials say

Biden has pledged to reopen most K-8 schools five days a week by the end of his first 100 days in office. Districts like Philadelphia underscore some of the challenges: The city’s traditional public schools are only open to prekindergarten through second-grade students whose families chose to have them return in person part time; third through fifth graders and sixth graders with complex special needs are eligible to return April 26.

Most district students are still being taught remotely, and there’s no return date slated for most sixth through 12th graders.

“What needs to happen is communication on how to safely reopen schools,” Cardona said in a brief interview Tuesday. “We need to continue to put our foot on the gas pedal. Our students can’t wait until the fall. If we can safely reopen now, we should be doing it.”

Yet, the education secretary also acknowledged that there are complicating factors in many districts, including Philadelphia’s, where buildings are old and in many cases have environmental problems. Olney itself was closed briefly for asbestos issues in 2018.

“I understand the infrastructure needs here are great, and I understand these buildings are a little old,” Cardona said, motioning across the gym in Olney’s annex — the school is overcrowded and lacks enough space in its main building for the whole school population.

Cardona, a former teacher, was confirmed last month after serving more than two years as commissioner of education for Connecticut. Clearly at ease in the classroom, he jumped in front of the camera Tuesday to wave to Meghan Harleman’s second-grade students who were learning virtually, and asked them to describe their class at Olney Elementary.

“Awesome!” one girl shouted.

“Kennedy, you said a fourth-grade word! Are you sure you’re not a fourth grader?” said Cardona, to cheers and smiles from the class, which included two students who had opted for in-person learning.

» READ MORE: Billions of stimulus dollars are coming to Pa. and N.J. schools to help get them open again

Educators have performed amazing work under difficult circumstances during virtual instruction, Cardona said. But “we know there’s no replacement for in-class learning,” he said.

In Upper Darby, Cardona went from classroom to classroom at Beverly Hills Middle School, greeting students at socially distanced desks.

Relatively few children were in some classrooms; in one case, just one student was present.

”So how do you feel about being the only student? Pretty good, huh?” Cardona said.

In another classroom, Cardona said hi to students through the teacher’s computer — in the chat, one student asked if he had a bodyguard — then asked the sixth graders sitting at their desks how they liked being back in person.

“You can’t show off your sneakers at home, right?” he said.

During a roundtable in the school library, Cardona heard from administrators and school board members, as well as high-schoolers Khalid Doulat, a sophomore, and Olivia Chamberlain, a junior, both of whom said they had struggled with virtual lessons.

Doulat said he now finds it difficult to talk to people in person — “I’ve lost touch of who I am,” he said. Meanwhile, Chamberlain said she was losing focus during online classes and felt intimidated about asking teachers for help.

Chamberlain recently returned to school, and “it was nice to have that breath of fresh air,” she said. “But you have to understand that it’s not going to be the same. I think that’s what a lot of people are afraid of. … They don’t want it if it’s not going to be the same.”

Their principal, Kelley Simone, said it had been a challenge to meet the needs of all families: Upper Darby High School has 3,800 students, and “not all our families have the same access,” she said.

”You run a city,” Cardona said, asking Simone how federal aid would help.

Going forward, schools will need to be more flexible than ever, Simone said: “You have to be able to offer in-person” learning, but some students “need to do it their own way. … We have to meet kids where they are.”