It looks as if the reopening timeline for Philly schools could depend on the school

“The time for reopening is now," Superintendent Hite said. He said one solution might be resuming classes in some schools and working to improving conditions in those where there are problems.

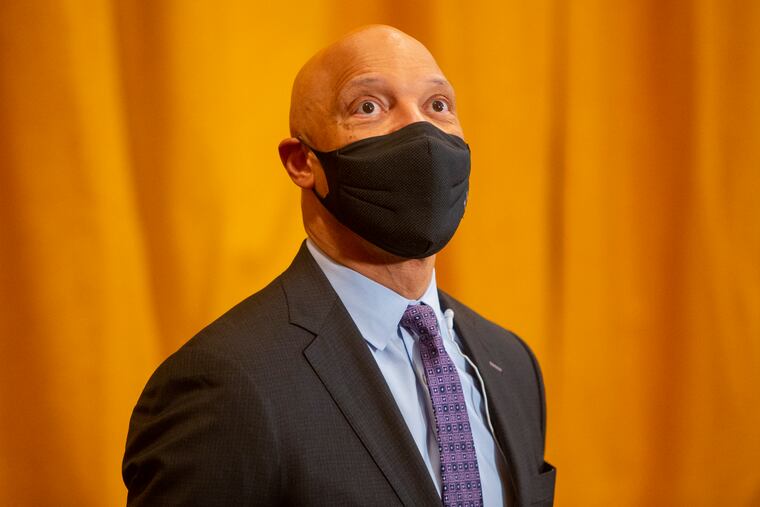

Superintendent William R. Hite Jr. on Thursday doubled down on his assertion that Philadelphia public schools are safe for children to return to in-person learning Feb. 22.

“I can confidently say that our schools are ready to open with the proper safety protocols in place,” Hite said at a news conference at Nebinger Elementary in South Philadelphia. “The time for reopening is now.”

The district is in a standoff with its teachers’ union, which has directed teachers not to report to school buildings because of COVID-19-related safety concerns. A mediator is weighing whether the district met the terms of its reopening agreement with the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers.

Susan E. Coffin, a Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia physician and infectious disease specialist who joined Hite, said in-school instruction can resume safely, even inside old Philadelphia buildings, if schools are vigilant about mask-wearing, social distancing, and having staff and students stay home if they’re feeling ill or have known exposures to COVID-19.

“It is possible to have an in-person education during this period,” Coffin said. “I think actually we’re entering a moment when it’s more possible than ever.”

Hite suggested one solution to getting teachers back in buildings would be opening some schools and working on improving conditions in others where there are problems. Philadelphia students have been out of buildings since March.

» READ MORE: Philly teachers don’t report to school buildings for a second day; teacher vaccinations expected to start Feb. 22

“Right now, this is an all-or-nothing conversation,” Hite said. “If there are schools that people are worried about, let us mediate those schools.”

Teachers were supposed to return to work Monday; instead, thousands stood outside school buildings, rallying and teaching from tents and beach chairs. Hite had threatened discipline for teachers who did not report but was forced to back down when the city intervened, telling teachers they did not have to show up until the mediator weighed in.

The mediator, Chicago doctor and public health expert Peter Orris, held his first session with the PFT and School District on Wednesday, Hite said. He noted that a state mediator is also involved.

“We were hoping to be in mediation a week or so ago,” the superintendent said.

Both sides began exchanging documents last week, but there’s no current timetable for when Orris might rule.

Hite said it was possible the Feb. 22 return for 9,000 prekindergarten through second-grade students could get pushed back, based on what and when the mediator rules.

Nebinger, the site of Hite’s first in-person news conference during the pandemic, is one of 32 district schools that lack mechanical ventilation and are using window fans to promote airflow.

» READ MORE: In public protest, thousands of Philly teachers pushed back against reopening schools

The fans have been controversial, derided as an inadequate fix for years of environmental problems, but Hite said they were never intended to be permanent.

“I know the fans may not look pretty or fancy, but scientifically, they do the job we need them to do,” Hite said.

Teachers have raised concerns about temperature controls inside rooms equipped with the window fans; district officials said building engineers will do two or three checks per day inside each occupied room, and if the temperature falls below 68 degrees, children will be relocated to another room.

The district has a history of environmental problems; some schools have routinely lacked basic supplies like soap and hot water. Teachers say subpar building conditions are slow to be addressed; at some schools, children and staff wear coats through the winter, and at others, everyone sweats.

Leading reporters on a tour of Nebinger, building engineer Joan Turrell used a gauge to check the temperature in one prekindergarten classroom. It was 84 degrees.

Turrell has worked at Nebinger for 18 years, and had kept reporting there through the pandemic, she said. Hite pointed out that building engineers, cafeteria workers, and some others have been in schools for months.

“No one said they weren’t safe for them to return,” said Hite.

About 50 Nebinger students signed up to return Feb. 22 two days a week, Hite said; citywide, only about a third of those eligible to return in the first wave chose in-person instruction. Teachers will be responsible for instructing both the children in the classroom and those working remotely.

Classrooms will look different when schools do reopen. Desks are spaced far apart — Nebinger rooms have glass partitions to keep children apart, and while the PFT’s agreement does not require them in every classroom, they will be provided for small-group instruction, Hite said. Every room has a section with personal protective equipment — sanitizer, masks, face shields.

Bright yellow stickers in hallways remind children to keep six feet apart. Every floor has a hand-sanitizing station. Materials will not be shared.

Class sizes will be small; the largest in Nebinger will have nine, school staff said. Each room has a sign outside saying how many people can safely occupy the space.

Hite said Thursday that the district will allow members of the public to tour buildings to help them gain confidence in school safety, but the details of the scheduled visits haven’t been worked out.

“We think the best and safest place for them to be is in school,” said Hite.

Still, fears remain for many.

Lea DiRusso, a longtime Philadelphia teacher, was diagnosed with mesothelioma, a deadly, asbestos-linked cancer, in 2019; she spent her career at Nebinger and Meredith, another South Philadelphia school. Teachers hold up DiRusso’s case and environmental and financial missteps on a major construction project at Benjamin Franklin High as reasons why they can’t trust officials’ promises, particularly around building safety.