A growing number of Philly-area school districts are planning virtual openings, relieving some parents and frustrating others

School leaders say they’re worried about the potential for continued spread of the coronavirus and too-slow test results. Some parents are questioning what it will take to ever reopen.

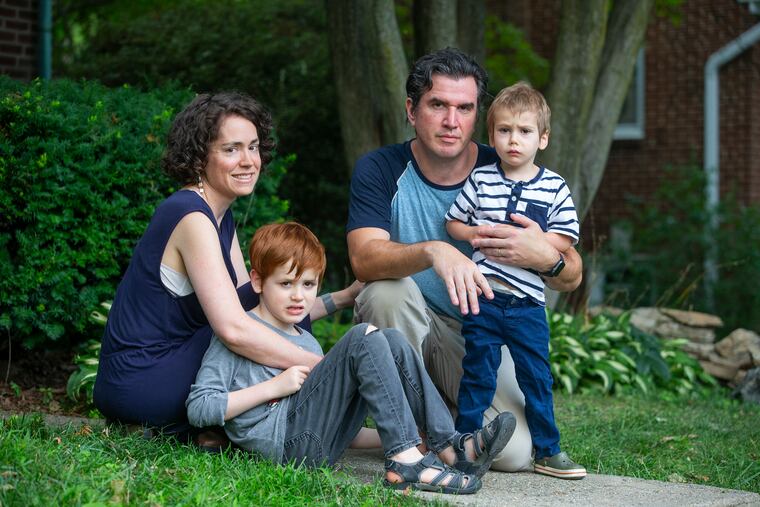

When his children’s school district announced that it would bring students back part time this fall, Alex Uram thought: We can handle this.

While working from home and supervising a rising kindergartner and third grader has been a challenge, the Montgomery County father, whose wife works in a medical facility, figured he could get his work done in the mornings and evenings on days his children weren’t physically in class in the Colonial School District.

He was stunned this week when the district’s superintendent recommended that schools only reopen virtually, upending his family’s plans.

“What has changed in the last two weeks from them approving a plan to ‘We can’t do it anymore'?” Uram said.

A growing number of school districts around Philadelphia are opting to begin the school year virtually — a shift that accelerated this past week, with boards all over the region approving and in some cases changing their plans on how to open in just a few weeks.

West Chester, Upper Darby, and Colonial were among the districts that approved virtual openings, as did Haverford — reversing course just one week after saying it would try a hybrid plan.

The rippling decisions have won support from parents worried about sending children back, but frustrated others now in a child-care bind — and fearing their kids will be forced to repeat what for many was a dismaying experience with virtual learning.

In Lower Merion, school board members spent four hours Wednesday debating considerations and hearing out parents — including advocates for an in-person return — before voting 8-1 in favor of a virtual plan.

Parents in a variety of communities have questioned why it isn’t safe to reopen, pointing to infection rates and recommendations from medical groups on the importance of in-person learning, including the American Academy of Pediatrics. (The group, which in late June said school plans “should start with a goal of having students physically present,” later warned against a one-size-fits-all approach, and called on Congress to provide resources for schools to reopen safely.)

In an interview with the Washington Post published Friday, Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious-disease expert, said: “Everybody should try within the context of the level of infection that you have to get the kids back to school.” He said states with “smoldering infections” should “tighten” reopening plans, possibly with hybrid in-person and online programs, while those with high levels of infection “may want to pause.”

School leaders around Philadelphia — which announced it would open virtually through mid-November — say they’re worried about the potential for spread of the coronavirus, and delays in getting test results. And as other districts have announced virtual starts, officials anticipate effects on their staffs, since teachers live in different communities and may have child-care issues.

» READ MORE: School reopenings are a mess, home-schooling ‘pods’ are coming, and they could make inequality even worse

Superintendents are also watching as some schools have reopened in other parts of the country, then shut down or imposed quarantines. They say they don’t want to bring students back only to close abruptly because of an outbreak.

“Why should we be the test case?” West Chester Area School District Superintendent Jim Scanlon said during a school board meeting Monday, explaining why he was recommending a completely virtual start even though just 20% of district parents favored that option. Like other school leaders, he pledged an improved virtual program from the spring.

In Millville, in South Jersey’s Cumberland County, the school district canceled its summer child-care program last week after a second staff member tested positive for the virus.

“[H]ere we are, a district that did our best, followed the protocols, and we couldn’t do it in a controlled environment, let alone when you go into a bigger, larger-scale situation in September,” Superintendent Tony Trongone told the Vineland Daily Journal. “What are we going to do?”

In Haverford Township, Superintendent Maureen Reusche asked the school board Thursday night to approve an all-virtual start, despite one week earlier recommending a hybrid reopening plan.

Reusche said she was concerned by Delaware County case data, as well as a model from University of Texas researchers that showed a school of 1,000 students reopening in Delaware County could expect five infected students to show up during the first week of instruction. She also said doctors from the University of Pennsylvania and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia had advised the district to wait to reopen, predicting a potential spike in cases after Labor Day weekend.

Reusche said she knew some parents would be upset, and “understandably so. This isn’t their choice,” she said. But, she said, “this isn’t anybody’s choice.”

Some parents argue that school leaders could open buildings in a strategic way, and should be trying to find in-person solutions — especially in affluent communities they contend should have the ability to make school environments safer.

In Lower Merion, Mark Fasano, who has children ages 7 and 2, thinks the district should reopen starting with its youngest students, reassessing every one to two weeks. He sees minimal risk in that approach, in part given the cases Montgomery County has reported among young children. (Of the nearly 10,000 positive cases the county has registered since March, 151 have been among kids 9 or younger.)

“We would not be OK with any in-person scenario that was unsafe — for anyone,” Fasano said. Like other parents, he questioned what it would take for the district to begin reopening, with no clear time frame for a vaccine: “This could take years.”

Pressed during Wednesday’s meeting, Superintendent Robert Copeland did not provide specifics on the public health benchmarks needed to reopen.

But he said he wanted faster testing, which would allow schools to perform more effective contact tracing — saying he had “grave concerns” about how many people an infected student could interact with before a test result was returned.

While parents may be willing to accept the risk, “I have the responsibility of recommending to the board what risk I think the school district should enter,” Copeland said. “And I think the risk would be too great.”

» READ MORE: ‘Every teacher I know is flipping out:’ As pandemic back-to-school plans form, educators are wary

Not all area districts are going virtual. The Wissahickon school board voted 6-2 on Thursday to stick with its plan to offer in-person learning five days a week for K-5 students, and a hybrid option for grades 6-12.

Other districts that have been planning varying degrees of in-person returns include Radnor, Central Bucks, and Unionville-Chadds Ford, which last week voted to hire 21 elementary teachers to reduce class sizes and ensure six feet of social distancing among students.

In the neighboring Colonial district, where the board voted 6-3 Thursday to start the year virtually, parents like Sully Francis said they understood the decision.

A bilingual counseling assistant in the Philadelphia School District, Francis worries about children, particularly in poorer districts like Philadelphia, not having their needs met while schools are closed. And as a parent of incoming fifth and third graders — the latter of whom struggled with virtual school in the spring — Francis knows in-person learning would help her children.

But she doesn’t think schools can open safely, staff can keep young children apart, or stop them from putting their hands in their mouths. “Our priority is supposed to be health,” Francis said.

On Thursday night, nearly 1,000 people stayed tuned into a YouTube livestream as the Colonial meeting neared midnight, five hours after it began.

Among them was Uram, who said before the meeting he would do anything to enable his children to return to school. “I will live my life as if I’m in the red phase for this entire school year. I will not go anywhere,” he said.

Later, he told the board, “You don’t seem to grasp the gravity of what you’re about to do to us as parents.”