‘You can’t help but feel empowered’: Philly exhibit shows the epic struggle for women’s right to vote

The curator for the National Constitution Center's new 19th Amendment exhibit found archival material that speaks volumes about the struggle for women's right to vote.

A century ago last week, the right of women to vote was enshrined in the 19th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution — a milestone in the fight for enfranchisement that arguably began with the formation of the country.

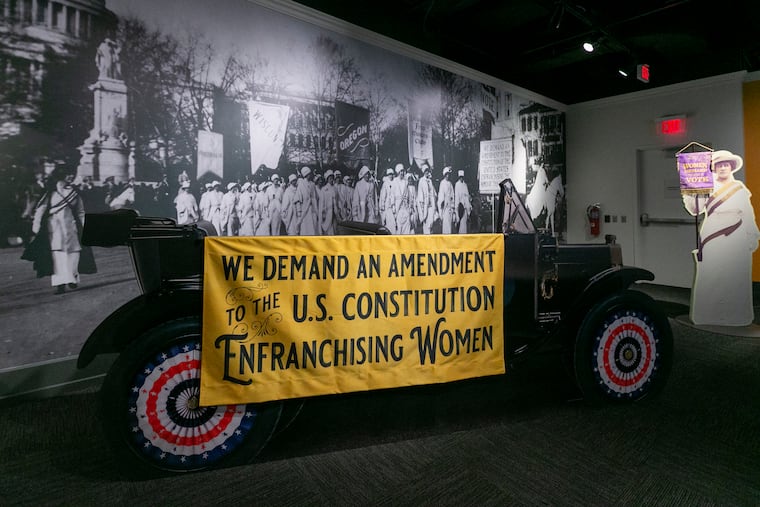

Because of the centennial marker, many institutions in the region and around the country have mounted commemorative exhibitions. The National Constitution Center has chosen an epic approach, seeking to cover the full sweep of the women’s suffrage movement from the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention though the Constitutional amendment in 1920 and beyond.

» READ MORE: Philadelphia’s Constitution Center planning big exhibition on 19th Amendment, which granted women right to vote

The new semipermanent exhibition was supposed to debut in the spring, but the coronavirus pandemic intervened. Now the “The 19th Amendment: How Women Won the Vote,” will open on Wednesday.

Elena Popchock, the NCC’s exhibition developer, spent over a year working on how and what to present in an exhibit telling the story of the 19th Amendment. She spoke to The Inquirer about the powerful stories she uncovered along the way.

The story is part of American mythology — did anything surprise you?

We’re taught that the movement starts in 1848, and we get to the 19th Amendment in 1920. That collapses so many efforts that are happening at the micro level in local communities, all the way to the national level of picketing the White House.

We have that threshold moment at 1848, you know, the movement begins. And then we zoom ahead to 1920, the 19th Amendment ratified. That just glosses over how many generations of women, and some men, fighting for this change, and spending their entire lives, hoping and pushing for women to get the right to vote.

A long time.

I think what is most surprising is just the generations. It encompasses three generations of people fighting. When you think of it in terms of generations, boy does that feel like a long time.

That’s something that really gave me pause and makes me appreciate their efforts and how they continue to fight, after time and again being either turned away at the ballot box during Reconstruction if they tried to go vote to when they’re fighting in the courts and they’re petitioning Congress. How you have that willpower to keep going, or to pass that on to your daughters and your granddaughters. I think that’s such a beautiful story that all of us can relate to on a very personal level.

» READ MORE: 100 years after 19th Amendment, voting rights and equality are still precarious | Editorial

We’re now in a time of another movement protesting injustice. The ongoing struggle of Black individuals for equal rights is another long, long American story. Does the suffragist movement have anything to say to Black Lives Matter?

I think it gives hope that there are so many avenues that we can take to push for Constitutional change. And there is a success story in getting the 19th Amendment ratified. Over those 70 years, they’re petitioning Congress, hundreds, perhaps thousands of times, and they’re not giving up. I think, learning from these women who continued to push for this change, and tried all different ways — I think there are things you can learn about how one pushes for Constitutional change and to become a more perfect union and live up to our founding ideals that all men and women are created equal.

Women used the courts, Congress, petitions, testimony, and they even sought to vote after Reconstruction.

And then the public-facing final few years of the movement where they’re picketing the White House — that was the first that the nation had ever seen picketing in front of the President’s residence. They organized these parades, a march on Washington in 1913 ― that’s the first national suffrage parade.

There was a big racial divide that emerged in the movement.

The story we’re told is more often of the white mainstream suffrage movement. Women of color were excluded from that. So when we tell that story, we’re very much overlooking the struggles and fights that they had in their own communities to pursue change.

Black women are forming by the 1890s their own groups because they’re experiencing mounting racism — when Jim Crow is starting to appear and become entrenched, not just in the South but across the country. ... There’s just a ton of issues that they’re having to deal with that the white mainstream movement isn’t necessarily having to, such as combating poverty, racism combined with sexism, and by World War I in particular, they’re having to push for anti-lynching legislation just to protect their lives and the lives of people in their communities.

How do you go about putting together such a sweeping, emotional narrative?

To begin with, I try to get a sense of what’s out there and what stories can be told through those tangible artifacts.

What’s out there?

For example, I came across a collection at the University of California, Berkeley — oral history, interviews that had been conducted in the 1970s of several suffragists. And one of them was a woman who had picketed the White House and then was arrested and put in jail. And so she’s recalling her experiences going from the picket line to prison.

And as soon as I was reading that I saw the potential for that story to be brought to life for visitors and feel as compelled as I did when I read it. We decided to get an actress to record parts of that transcript. So it feels as though you’re looking through these jail cell bars, and you’re watching this woman recall her experience but you’re there taking part — you’re right there with her.

Did you use actors for anything else?

We found this handwritten speech by Mary Ann Shadd Cary at Howard University in D.C. She was the first Black female law graduate from Howard. She’s very significant. ... This moment in 1874, she actually appeared before the House Judiciary Committee, probably one of the first times that women were allowed to be heard in a hearing in the Congress.

She took part, and it’s her words in the speech that are just amazing, how she recognizes the color of her skin. She literally says she may not add one iota of weight to the arguments of the other learned women here. So she’s recognizing, you may not place any weight on what I’m saying, because of the color of my skin, but I’m going to say it anyway.

And she goes on to argue that American citizenship should be shared equally. And this is during Reconstruction. So, it’s such a beautiful speech that you see this story inserted into that narrative that we’re told, and it just adds so much breadth and depth to it that you can’t help but feel empowered.