New ‘Spaceship Earth’ movie stars the human lab rats who self-quarantined in Biosphere 2. We talked to one.

Mark Nelson and fellow "biospherians" were sealed off together for two years and pushed to the limits of endurance. So, no, he doesn’t want to hear about glitches in your high-speed internet, or faulty service from Grubhub.

If you’ve got complaints about the COVID-19 lockdown, don’t take them to Mark Nelson, a star of the new documentary Spaceship Earth, which has the pandemic equivalent of an opening this weekend — streaming on demand and playing a few drive-in theaters nationally.

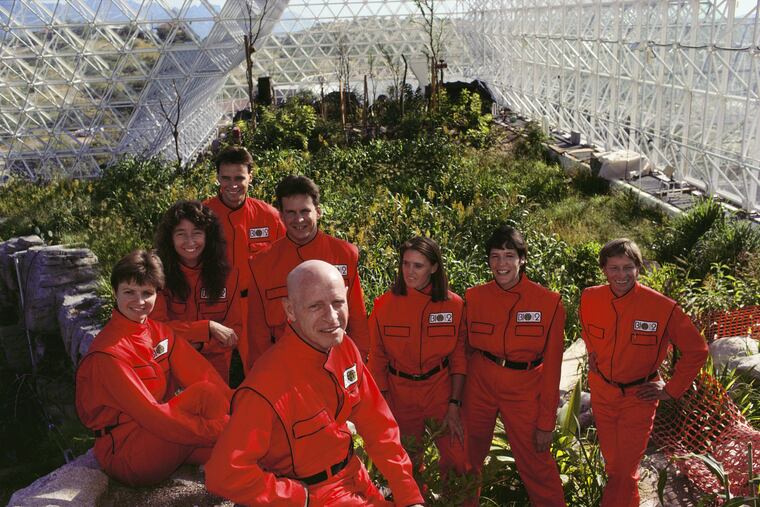

The movie tells the story of Biosphere 2, a $150 million man-made, self-contained ecological system (no relation to the Pauly Shore movie), that, starting in 1991, was sealed shut and inhabited by volunteer “biospherians,” including Nelson.

He was isolated in the seven-acre Arizona facility with seven other people for two years. As we see in the film, he and the others were pushed to the limits of endurance and tolerance — nerves frayed by stress, bodies emaciated by limited food, a mind altered by the dangerous drop in oxygen levels.

So, no, he doesn’t want to hear about glitches in your high-speed internet, or faulty service from Grubhub.

The folks in Biosphere 2 could eat only what they grew in the dome, breathe the air they generated and filtered internally (at least this was the intention), and entertain one another with group theater, which Nelson probably likes more than you.

“You learn a lot about quarantine and isolation and about the conflicts that come up, and what’s gets you through those affairs,” said Nelson.

He said biospherians (that’s what they call themselves) endured by remembering and reaffirming why they were locked in the dome in the first place. Nelson advises us to do the same — remind ourselves that we are distancing to save lives, an important and worthy sacrifice.

» READ MORE: How not to destroy your relationship while spending 24/7 together during coronavirus quarantine

“I think the most important factor was having a shared objective. There were certainly times where at the end of the day, I detested the other people, but the main thing is we were working together,” he said. “And there were also those days when we were having a hell of a good time, and at every moment we were all committed to the success of the project, and we worked like to hell to make it work.”

Nelson concedes that he had an advantage. His fellow biospherians were close friends and an “inherently optimistic” group of folks committed to proving a point about ecosystems and sustainability.

Still, it wasn’t long after the door was closed and sealed that they came to grips with the claustrophobic finality of their situation. To use a more modern cultural reference, he said, they “were on a reality show, but nobody could be voted off the island.” Tourists paid money to gawk from the outside.

He sympathizes with folks who find themselves cohabitating abruptly and involuntarily, where group goals are not necessarily aligned, as they were in the Biosphere.

Nelson, now an ecological researcher, educator, and consultant (and still an organic farmer), put it this way: “If the dynamics are bad, you have a problem. For me, it would be like being in a faculty meeting and being told you couldn’t leave for two years.”

Spaceship Earth, directed by Matt Wolf, is an entertaining and comprehensive revisiting of the Biosphere 2 project, which was conceived and executed by what Wolf called an “intentional community” and what the mainstream press at the time often referred to as a “cult.”

They were led by John P. Allen, a charismatic figure (certainly among his enthusiastic entourage) who drew to him (in 1960s San Francisco) a disparate collection of mostly (compared to Allen) younger people who shared his enthusiasm for environmentalism.

They started a theater troupe, took up organic farming, built their own boat and sailed it around the world, and then hit on the idea for a closed ecosystem (rain forest, “ocean,” wetlands, etc.) that could generate its own air and food, and demonstrate to world the efficacy of sustainable methods.

By the way, it was called Biosphere 2 to call attention to the fact that the earth itself is Biosphere 1. The implication, underscored by the project: We need to learn how live within the planet’s finite capacity to sustain us.

How this massive project was funded (and how it played out) is part of the documentary’s rollicking narrative, so we won’t spoil it here. Ditto the fate of the Biosphere after Nelson and his friends emerged, and a Certain Someone took control of the installation and turned it into a more conventional profit center.

We can say, however, that Spaceship Earth exhibits Wolf’s signature style — he is on a journey to learn about people, not to judge them, and his open-minded, searching curiosity creates a bond of trust with the viewer.

This same approach was evident in his previous film, Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project, which took a fascinating look at the life of Philadelphia eccentric Stokes, who became a recluse and recorded 30 years of television in her Rittenhouse Square apartment, creating a one-of-a-kind archive in the process.

» READ MORE: This Philadelphia woman recorded three decades of television on 70,000 VHS tapes

Wolf found something visionary and prescient in Stokes’ unusual activities, and does the same thing here.

“Biosphere 2 was [in many media circles] discounted as a fraud and a failure, and the group was called a cult, and I am always skeptical of that kind of thinking,” said Wolf, who nonetheless is duty bound to point out in the movie the endangered biospherians eventually had to scrub the air with external filters, a fact they were initially not eager to disclose to the press, leading to harsh, derisive, and deserved media criticism.

“I was impressed by the scope of the idea, even if you accept that aspects of it were flawed. I was also intrigued by the idiosyncrasies of the group, which defied established categories. They were not hippies, and actually were more comfortable calling themselves capitalists, and they were not just scientists but also artists and explorers and adventurers,” he said.

Though derided at the time as “ecological entertainment” rather than useful science, Biosphere 2 — still attracting tourists today — has a valuable legacy, Nelson said.

“We wanted to demonstrate, and I think we did, this idea that ecology could be an adventure,” said Nelson, who’s written about his experiences (“Life Under Glass: The Inside Story of Biosphere 2”) and continues to teach about his experiences. “I can tell you that we inspired a gazillion kids to think about ecosystems in a way that is exciting to them, and I’m proud to have been a part of it, because I think it is more relevant today than ever.”

The movie is available on demand, and can also be accessed though streaming links via many independent theaters, including the Philadelphia Film Society, Lightbox Film Center, and Renew Theaters’ four suburban venues (the Ambler Theater, Jenkintown’s Hiway Theater, Doylestown’s County Theater, and Princeton Garden Theatre).

If you stream via the website of your local art house, a portion of the revenue goes to that venue. For a complete list, visit neonrated.com, the website of the distributor Neon.