The boozy business of the American Revolution went down in Philly bars

Revolutionary-era drinking and tavern life, and its role in America’s founding 250 years ago, will be explored in full at a Nov. 21 after hours event at the Museum of the American Revolution.

The Founding Fathers never suffered sobriety. When they weren’t sweating out independence at Independence Hall, they were bending elbows at City Tavern — pretty much around the clock.

George Washington developed such a hankering for a rich, malty, Philly-brewed Robert Hare’s porter, he had kegs of the stuff shipped to Mount Vernon.

John Adams, once virulently anti-tavern, effusively extolled the Philly bar scene in letters to his wife, Abigail. At one “most sinful feast,” Adams recalled sipping what would become his favorite Philly cocktail, the “Whipped Sillabubs.” A popular choice of the colonial-era Philly cocktail set, the boozy, creamy concoction was made from sherry, wine, and lemons.

Thomas Paine, the working-class poet, whose thunderous pamphlet Common Sense helped roar in a revolution, oiled up his writing hand with Philly rum.

It has long been accepted that Thomas Jefferson spent those sweltering summer weeks of 1776 drafting the Declaration from the favored Windsor chair of his Market Street lodgings. But records show he actually spent more time than ever at City Tavern at Second and Walnut. A minor, if tantalizing, historical development, which hints that perhaps the world’s most famous freedom document came fortified by fortified wine.

Benjamin Franklin, polymath of the Revolution, inventor, scientist, printer, statesman, and lover of French wine (if in moderation), affectionately penned a Drinker’s Dictionary. The tippling tome contained 229 of Franklin’s favorite phrases for drunkenness, including buzzy, fuddled, muddled, dizzy as a goose, jambled, halfway to Concord, and Wamble Cropped.

‘Boozy business of revolution’

Franklin and his ilk were not ringing up 18th-century expense accounts for the hurrah of it. They were doing the boozy business of revolution.

Revolutionary-era Americans consumed staggering amounts of alcohol compared with today, said Brooke Barbier, historian and author of the forthcoming book Cocked and Boozy: An Intoxicating History of the American Revolution.

By the end of the 18th century, when beer and spirits were a staple of daily life, the average colonist swilled about 3.7 gallons of hard liquor per year. A dizzying amount, not counting beer and cider, that must’ve set many a patriot’s tricorn hat spinning.

By comparison, Americans now consume about 2.5 gallons of all alcohol, from beer to whiskey to wine, per year, said Barbier.

Historians believe booze and bar life played an outsize role in stoking the embers of insurrection.

“Tavern culture was essential to the American Revolution,” said Barbier. “It was not a part of the sideshow. It was part of where the discussions about revolutionary ideas happened. Where spies met. And where others, who weren’t directly involved in politics, gathered to discuss the growing political crisis. Opinions were formed in taverns.”

Nowhere was this work done more than in Philadelphia.

By 1776, Philadelphia boasted roughly 200 licensed and illegal watering holes — or about one for every 150 citizens, said Tyler Putman, senior manager for gallery interpretation at the Museum of the American Revolution.

Revolution with a twist

The fare of colonial-era drinking spots was as diverse as the budding port town.

There were posh spots like the newly constructed City Tavern, located blocks from the waterfront, and where the delegates of the First and Second Constitutional Congress drank nightly like fish. Ensconced in an upstairs space, known as the “Long Room,” the Founding Fathers debated liberty over libations late into the night, while imbibing copious amounts of Madeira, whiskey, punch, and everybody’s favorite Robert Hare porter.

There were taverns and flophouses, where tradesmen and sailors learned of Britain’s newest outrage from newspapers read aloud, or the latest traveler. And there were scores of unlicensed disorderly houses, grungy forebears of the modern dive bar.

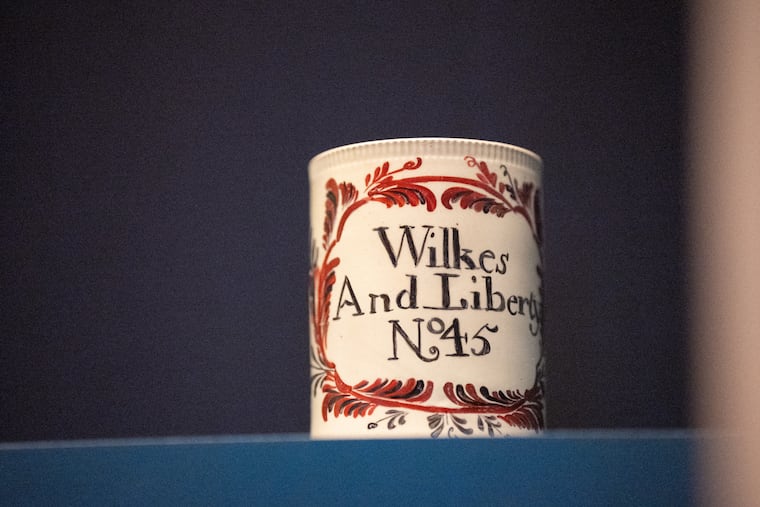

In 2014, three years before opening, the Museum of the American Revolution conducted a large archaeological dig, discovering thousands of artifacts from a Revolutionary-era disorderly house buried beneath its future Old City home. Among the mounds of mutton bones, glassware, and broken bottles unearthed from the privy of Benjamin and Mary Humphreys’ living room tavern was a broken windowpane inscribed with the initials and names of customers.

In what can only be the earliest example of Philly barroom graffiti, one dreamy patriot etched a quote attributed to the ancient Roman senator Cato into the clouded glass: “We admire riches and are in love with idleness.” The etching was meant as a barb toward the British, Putman said.

“They were obsessed with ancient Rome,” he said, of the American revolutionaries. “They were thinking a lot about, ‘How do you go back to some sort of idealized republic?’”

A nation born in taverns

Just as the nation strived to become democratic, its taverns became more undemocratic.

“In Philadelphia, the elites who are cooking up one version of the revolution are not drinking with the rabble who are cooking up what maybe would become a different version,” Putman said.

Revolutionary-era drinking and tavern life, and its role in America’s founding 250 years ago, will be explored in full at a Nov. 21 after-hours event at the Museum of the American Revolution. Dubbed “Tavern Night,” the sold-out cocktail reception and boozy symposium serves as a twist to the museum’s grand exhibition celebrating the national milestone, also known as the Semiquincentennial, "The Declaration’s Journey."

“Unlike today’s bars, taverns were meeting places at a time when few others were available,” said Dan Wheeler, who last year reopened Philly’s only remaining colonial-era tavern, A Man Full of Trouble, and will join Barbier in speaking at the event. “Revolutionary thoughts were conceived and refined in taverns, and a nation was born.”

Colonial keggers and the bonds of liberty

Booze was the social lubricant of the Revolution, said Barbier, a Boston-based historian who also runs tours of Revolutionary-era taverns, who pored over the Founding Fathers’ diaries and account books in recreating their raucous time in Philly.

The historical record provides no evidence that the nation’s founders were fully loaded — or “cock-eyed and crump-footed,” as Franklin might’ve said — as they went about forming the republic, she said.

“When you hear someone accusing someone of being drunk, it’s in an overly negative way,” she said.

Still, she was surprised by just how much the Founding Fathers drank.

Hard cider and small beer, the 18th-century version of light beer, more or less, accompanied breakfast, she said. The midday meal, known as dinner, boasted cider, toddy, punch, port, and various wines. When their workday wrapped up in the late afternoon, the delegates’ drinking began in earnest.

“There’s certainly a lot of drinking happening in these taverns,” said Barbier, whose book includes recipes of the Founding Fathers’ preferred aperitifs. “I don’t drink and not eventually feel tipsy. Certainly the same would be true for people in the past.”

Barbier notes the downside of all the drinking, like booze-fueled mob violence that spilled into the streets. And neither will she say that Jefferson, who kept all his receipts, actually penned the Declaration at City Tavern.

“He was there more frequently than ever during this time,” she said. “Maybe he needed to take a break from his writing, and go there. And sometimes when you’re on break, you develop your best ideas.”

The Founders’ endless toasting of tankards — including a rager for the ages marking Paul Revere’s arrival in Philly, and held in 1774, the night before a critical vote toward independence — provided crucial trust-building, Barbier said.

The men who founded America arrived in Philly as strangers, agreeing on little. After so much boozing, they bonded as brothers in liberty, and left a new nation in their wake.

“Ultimately, this comradery and social bonding leads to the consensus that leads to the Declaration of Independence,” Barbier said.