UPenn scientists among those developing vaccines that arm the immune system to fight cancer

The Cleveland Clinic is trying to stop the recurrence of triple-negative breast cancer while John Hopkins is targeting pancreatic cancer.

University of Pennsylvania is among the leading cancer institutions working to develop a vaccine to prevent cancer.

Many of the vaccines in development, including Penn’s, share the thesis that the body’s own immune system may be medicine’s best weapon against cancers.

“We just have to figure out how to best deploy it,” said Susan Domchek, executive director of the Basser Center for BRCA at Penn.

Domchek and her peers at other cancer institutions acknowledge their efforts may never make it through the years-long process to prove they are safe and effective for widespread use.

Domchek leads a team developing a vaccine for breast cancer related to the BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations, which are associated with high risk of cancers of the breast, ovaries, pancreas, and prostate.

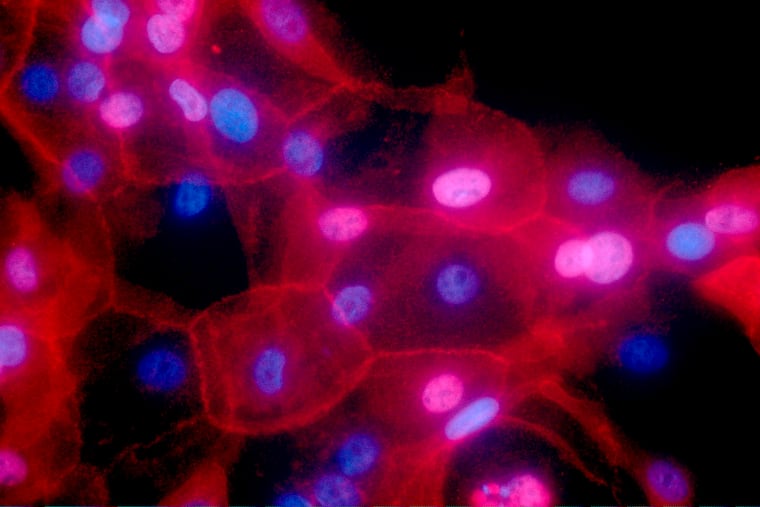

Penn’s vaccine uses bits of DNA, shot into the arm and pushed deep into white blood cells with a jolt of electricity. The vaccine teaches the immune system how to recognize and attack an enzyme that is a catalyst to growing cancer cells.

» READ MORE: Penn’s BRCA cancer vaccine trial aims to prevent the disease in healthy people

Cancer vaccines in development

Johns Hopkins University is also working on a vaccine for BRCA gene-linked pancreas cancer. It uses deactivated pancreatic cancer cells to train the immune system to better recognize the earliest signs of precancerous cells.

The Cleveland Clinic is trying to stop the recurrence of an aggressive and hard-to-treat form of breast cancer, called triple-negative breast cancer, that is common in among carriers of BRCA gene mutations. The Cleveland Clinic’s vaccine targets the overactive lactation proteins involved.

“There are a lot of targets to attack with vaccines, we just have to figure out which targets are the most relevant — and it won’t be the same for every person,” said G. Thomas Budd, a cancer doctor at the Cleveland Clinic who is leading their vaccine trial.

Penn also wants to pursue cancer vaccines using messenger RNA, the linchpin of the first COVID-19 vaccines that won a Nobel Prize for two Penn scientists. In the COVID-19 vaccines developed using mRNA, a small portion of the virus’s genetic code is used to stimulate the body to create a protein that triggers an immune response.

Now the Penn lab led by Nobel laureate Drew Weissman is exploring whether mRNA could be used to prevent BRCA-related breast cancer from developing, said Robert H. Vonderheide, director of Penn’s Abramson Cancer Center.

As with COVID, applying mRNA technology to cancer vaccines could yield an effective, widely accessible vaccine, said Elizabeth Jaffee, the deputy director of Hopkins’ Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center.

DNA-based vaccines, like Penn’s, meanwhile, may be less accessible to patients, since they require use of a specialized electroporation machine. And protein-based vaccines, like Hopkins’, are delicate to manufacture and store commercially.

Trials at Penn, Hopkins, Cleveland Clinic, and elsewhere are ongoing.