CHOP is celebrating 100 years of pediatric research. Two leaders talk about the opportunities for the next century.

Children's Hospital of Philadelphia is celebrating 100 years of pediatric research by reflecting on medical advancements over the last century.

Pandemics have bookended a century of pediatric research at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

When CHOP established its first research laboratory in 1922, one in five children died before their first birthday. Antibiotics didn’t exist, nor did most vaccines.

One hundred years later, CHOP is looking back on its role in advancing the health of children and babies. Its contributions include groundbreaking vaccines — for whooping cough, rabies, rotavirus — and revolutionary treatments such as the first approved gene therapy.

» READ MORE: One in five Philadelphia newborns is not protected from measles, CHOP-Penn study finds

The 100-year anniversary festivities started last year but the pandemic pushed many in-person events into 2023, including a “Meet the Experts” lecture series and Science Slam competitions where early-career researchers present their work in less than three minutes.

Major advances that started at CHOP

A look at the past century of CHOP research showcases the health trends of American children. CHOP did the first study on homogenized milk, which demonstrated how cow’s milk could serve as a substitute for babies who didn’t have access to breastmilk.

“Fast forward to now: Rather than nutritional challenges like that, we have researchers studying obesity and diabetes,” said Susan Furth, chief scientific officer at the CHOP Research Institute, the hospital’s research arm.

CHOP’s researchers in the 1940s and ’50s began to understand the structure and importance of DNA and the human genome.

By 1999, CHOP led the first human gene transfer studies for hemophilia, a bleeding disorder. And since, the list of disorders that pediatricians can treat using the technique has grown.

A focus on ethics

The first researcher at CHOP, virologist Joseph Stokes Jr., received the Medal of Freedom in 1946 from President Harry Truman for his work on treatment for hepatitis A and B.

But Stokes’ research practices today would be considered unethical. He tested vaccines on school-aged children, including youth with intellectual disabilities, and incarcerated women.

» READ MORE: Philadelphia has a rich history of vaccine research and development

CHOP works to ensure that past mistakes aren’t repeated, Furth said. In addition to internal study ethics standards, CHOP includes patient families on committees tasked with shaping research protocol.

The process is “becoming much more of a partnership and collaborative relationship” between researchers and patient families, Furth said.

CHOP also requires trainees to undergo ethics training, said Wendy Reed Williams, senior director of academic training and outreach programs at the Research Institute.

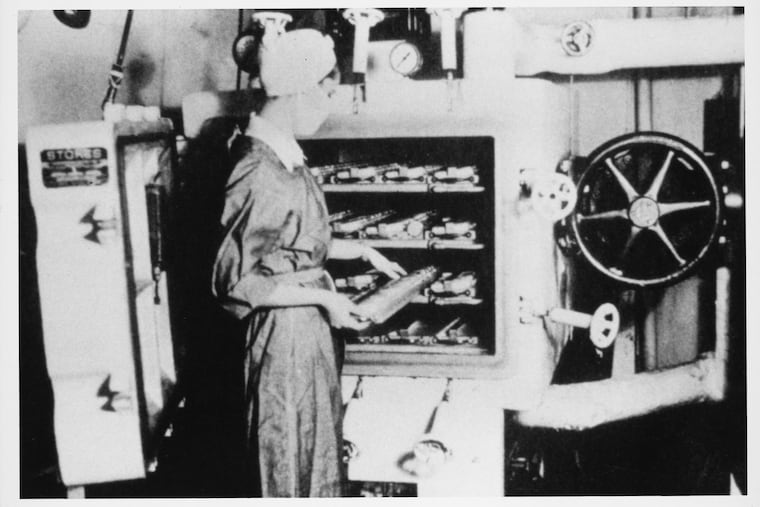

When Stokes established the first lab in a hospital basement, the researchers around him were white men like him. Each largely worked alone.

Researchers today work in teams, Reed Williams said. And CHOP’s goal is to have those teams represent the city.

“That’s diversity in terms of thought and perspective that goes into the work,” she said.

Anticipating CHOP’s next 100 years

Williams and Furth see a bright future in pediatric research, with big advances on the horizon.

Furth expects CHOP’s next big milestones to come from the field of precision medicine, which uses large amounts of genetic information to tailor each patient’s treatment plan.

“Using big data to understand unique signatures of disease is really going to be our next step forward,” she said.