Millions have lost a loved one to COVID-19. Grief’s mental and physical burden is especially heavy on kids.

Research has shown that children with unresolved grief are at risk of poor mental health, including depression and substance abuse; and long-term physical health complications, such as heart disease.

Nissah Coverdale doesn’t remember exactly what her mom said when she sat down the 11-year-old and her three siblings that day in May 2020, but the message was one that would change her life: Pop Pop had passed away.

Nissah wasn’t sure what to think or how to feel.

Sad? Confused? Angry?

Before the pandemic, Nissah, her older brother and two younger sisters saw their grandfather several times a week, combing the dollar store shelves for treasures or binge watching sitcoms after school. Even after his dementia forced him to move to a skilled nursing facility, they visited as often as they could to chat and play games in his room.

Michael Coverdale was diagnosed with COVID-19 in May, and his health declined quickly. He died May 27, 2020, at age 63.

“I just went into the living room. I just wanted to be alone,” Nissah recalled this week, paging through an old photo album in the family’s West Chester living room. “I didn’t go outside for a long time because I didn’t want to talk to anyone.”

Hardships of the pandemic have touched virtually everyone, whether they’ve lost a relative or friend to the virus, experienced unemployment, food shortage or even homelessness. But the emotional burden of a disease that disproportionately kills middle-age and older adults has been especially heavy and heartbreaking for children.

An estimated 40,000 children in the U.S. have lost a parent because of COVID-19 — a 17% to 20% increase over the annual average, according to a study by researchers at Stony Brook University and Penn State University published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in April. At least 2 million children lost grandparents, who have increasingly been called on as caretakers during the pandemic, as parents continued to work while their children’s schools operated virtually. By comparison, about 3,000 children lost a parent in the Sept. 11 attacks.

Experiencing loss at a young age is about more than grieving a death. Primary caretakers are children’s main source of safety and comfort, which means children must mourn the loss of a loved one while also learning how to navigate the world without their north star, just when their normal routines already were upended. Their family’s financial stability may be shaken, leading to housing and food insecurity.

Talking to children about death is never easy, but there is so much at stake for children who do not learn how to process their grief. Research has shown that children with unresolved grief are at risk of missing school; experiencing poor mental health, including an increased risk of depression, substance abuse, and suicide; and long-term physical health complications, such as heart disease and high blood pressure.

“We’re losing ground by not paying attention to children and children’s grief,” said Rachel Kidman, social epidemiologist and an associate professor at Stony Brook University, who was the lead author of the JAMA study. “This is not something we can come back to when the pandemic subsides.”

» READ MORE: What you should know about grief after COVID-19 deaths

‘We’ve been bracing for this’

While some Philadelphia-area bereavement centers say they have already seen an increase in demand for their youth services, others are bracing for a surge as children return to schools, which provide an important connection to support services for families.

“The wave is still rising and we’re just barely skimming the surface. We’ve all been bracing for this,” said Mary FitzGerald, CEO of Eluna, a Philadelphia-based nonprofit that provides youth grief counseling and sponsors kids’ bereavement camps. “People are overwhelmed and people are grieving. They’re dealing with other pandemic issues, like job losses, and we’re not seeing the outreach yet.”

In May 2020, Uplift, which runs 200 support groups for children in Philadelphia public schools, launched a grief support line for teachers, students, and caregivers. Philly HopeLine is staffed by trained clinicians, who can offer help right away or connect families to support groups or other resources, and has special hours for Spanish-speakers and LGBTQ+ youth.

“There’s grief from death but there’s also a lot of loss people have had in terms of relationships because they weren’t in school,” said Kevin Carter, the organization’s clinical director. “We anticipate ... a lot of the loss they may not have recognized is going to surface.”

Penn Medicine’s bereavement program, which offers counseling to the community and to families who lose a loved one in hospice care, the client base has more than doubled since the beginning of the pandemic, and the health system has added counselors and expanded spiritual support services to keep up with demand.

Social isolation from friends and extended family, and losing the distractions that going to work or school has made coping with grief harder, said Michelle Brooks, director of psychosocial services for Penn Medicine at Home. About 25% of hospice care families now participate in Penn’s support groups and workshops, up from 15% before the pandemic.

“It’s had a significant impact on how people experience life and death,” Brooks said of the pandemic. “There’s been so much loss, there’s a lot of understanding that whenever we lose someone new, we reexperience old losses, and they may not all be losses through death, but those feelings emerge and light each other up.”

How children grieve

Grief is not a linear process with a defined end point. That can be a difficult concept for children, and the journey of grief’s peaks and valleys is all the longer for those who lose a loved one at a young age.

“Children re-grieve, over and over as they age. They have to integrate the loss as they grow and move through different milestones,” such as Mother’s Day, graduation, or a wedding, said Bethany Gardner, Eluna’s director of bereavement programs. “It’s a process through life. Grief is not something we look to end or resolve.”

Caregivers often struggle with how to help children, especially young children, cope with death because they inherently want to shield them from hurt, said Aparna Kumar, a mental health nurse-practitioner at Thomas Jefferson University who specializes in child psychiatry, who has written about the pandemic’s toll on mental health for the website Dear Pandemic.

» READ MORE: The pandemic made grief harder. Some may need help.

They may think they’re doing the right thing by putting on a smile and acting as if nothing happened, but they’re not, she said.

“We almost tiptoe around the subject of grief and loss. It’s not a comfortable conversation to have,” Kumar said. “But it’s important to allow children to express their feelings and know it’s normal to be sad.”

Natosha Coverdale’s children hadn’t seen their grandfather since the middle of March 2020, when visitors were banned from his nursing facility. Though she worried her father’s worsening dementia would mean he didn’t understand why they stopped visiting, she tried to stay positive for the kids.

“We were in the midst of just praying and hopefulness until that moment when I was afraid to tell them it was going to be OK, because I knew it wasn’t,” said Coverdale, 37.

When Coverdale got the call that her father had died, she didn’t tell the kids right away. She went to see him one last time, closed his eyes and sat next to him and cried.

Then she went home to share the news.

“I’m one of those people to say how you feel. If you gotta cry, you cry. We all hugged each other and we cried,” she said. “I didn’t want them to feel they had to suppress it.”

Talking to kids about death

Children grieve as part of a family, Gardner said, which means it’s important for adults in the home to take care of their own mental health, to set a healthy example of how to cope.

“It’s important that adults are open — it frees children to grieve,” she said.

While Coverdale encouraged her children to be open about how they were feeling, she struggled with processing the death of her father, whom she considered her best friend. She felt sad that the man who’d worked so hard his adult life had never gotten the chance to relax, take a vacation, and do the things he envisioned in retirement.

“For a long period of time I just wasn’t OK. I’m still not OK,” she said. “One of the biggest things for myself is actively seeking help, saying, ‘I’m not doing OK right now, I need help.’ ”

Being open about how she’s feeling has helped her children feel comfortable admitting that they feel sad, she said.

How children interpret death and their coping mechanisms will likely evolve as they reach new developmental phases.

Young children, for instance, are the center of their own worlds and draw direct lines or “magical bridges” to events that happen and their own actions, Gardner said. Avoiding talking about death with young children could lead them to blame themselves.

Older children who are able to understand death may struggle with the indefinite feelings of sadness and loss they are experiencing. Others may cope relatively well with a death initially, only to experience extreme grief years later.

Acting out, feeling sad and carrying on as if nothing happened are all normal reactions to death for children, said Carter, of Uplift. While talk therapy is often helpful for adults, children may be better able to express their emotions through art or music.

Coverdale’s 17-year-old son, who was especially close to his grandfather, became quieter and now spends a lot of time alone, in his room. The baby of the family, who is 4 and still working to understand death, asked recently if Pop Pop would be coming from heaven to collect his birthday presents in October.

“It’s hard because they all have different personalities and express themselves differently,” she said.

Nissah initially struggled to channel her emotions, and became upset anytime someone mentioned Pop Pop.

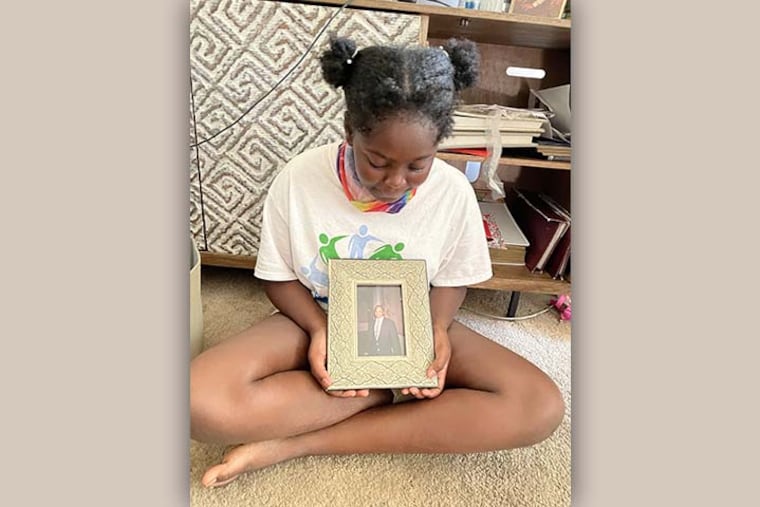

Lately, she’s doing much better. Pop Pop took pictures of everything and amassed a huge collection of family snapshots. With her mother’s help, Nissah went through the old albums and picked out her favorites to put in her own, special album.

Looking through it, she laughs at the funny old hairstyles and balks at her grandfather molding a snowman without mittens.

She wants other children who’ve lost someone they loved to know they don’t really lose them, they have them in their heart, she said. “And make sure to take lots of pictures.”

Call Philly HopeLine if you need help coping with a loss, isolation or other emotional challenge during the pandemic. 1-833-PHL-HOPE (1-833-745-4673)