Penn finds that using automated texts to monitor COVID-19 patients at home saved lives

Patients in the program went to the emergency department faster and were given steroids earlier.

Just two weeks after COVID-19 shut Philadelphia down in March 2020, Penn Medicine had already reengineered a program designed to monitor lung disease patients so that its staff could keep tabs on those suffering from the new virus at home.

Doctors quickly realized there was a “huge swath” of patients who had tested positive but were not sick enough for the hospital — yet, said Krisda Chaiyachati, medical director of Penn Medicine OnDemand. By then, it was clear that people with COVID-19 who at first seemed fine could deteriorate rapidly. As a result, many were already extremely sick — sometimes too sick — by the time they got to the emergency department.

On March 23, Penn began offering an automated texting program called COVID Watch designed to quickly identify patients whose condition was worsening and decide which ones needed to go to the hospital. On Monday, the first analysis of the program’s impact was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine. The conclusion: “Lives were saved,” said Chaiyachati, one of the study’s lead authors.

The study found that, between March 23 and Nov. 30, 2020, the risk of death in the group that received the texts was 64% lower than it was for patients who received usual care. It followed 3,488 patients who had contact with the Penn system and chose to enroll in COVID Watch and 4,377 similar patients who did not. COVID Watch patients had 1.8 fewer deaths per 1,000 at 30 days after testing and 2.5 fewer deaths per thousand at 60 days. The results held for white, Black, and Hispanic patients.

The death rate was well below 1% in both groups, an indication of less severe illness in people who did not need immediate hospitalization. At 30 days, three of the COVID Watch patients and 12 of the usual-care patients had died. At 60 days, the death toll was five for COVID Watch and 16 in usual care.

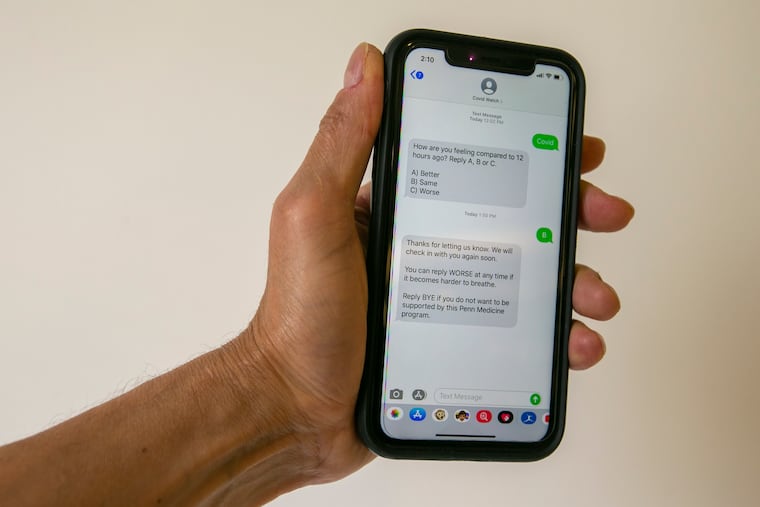

Those in the usual-care group would have been responsible for talking with their primary care doctors or seeking in-person care if they felt sicker. COVID Watch patients got texts twice a day asking how they felt compared to 12 hours earlier. Those who said they felt worse received a follow-up question: “Is it harder than usual for you to breathe: yes or no?” Because doctors considered breathing trouble to be the best sign of serious illness, patients who said “yes” to that question were contacted within an hour by a telemedicine clinician. Patients could also get a call by texting “worse” at any time.

On average, patients in COVID Watch who went to the emergency department at Penn did so three days earlier in the course of their illness than those in usual care. They also started treatment with steroids, which can prevent an overreaction of the immune system, earlier. “We think that is the mechanism by which we prevented deaths,” Chaiyachati said. None of the patients who received texts died outside of the hospital compared to six in the usual-care group.

A big advantage of the automated approach, Chaiyachati said, is that, at a given time, two to four staff members could oversee more than 1,000 patients. “We could do this program with almost like a SWAT team of nurses,” he said. In total, around eight nurses were assigned to COVID Watch.

The program was designed both to soothe patients who were doing well but were anxious and to prod patients who were getting worse to seek extra help. Patients who did not see improvements after several days also received calls even if they weren’t getting worse.

The program is still in action, and it so far has enrolled 20,000 people. Starting in December, new patients received pulse oximeters, which measure oxygenation levels. Those were very hard to get during the initial study period. A study on how that affected results is near completion, Chaiyachati said.

» READ MORE: What’s a pulse oximeter and do you need one to monitor for coronavirus?

As vaccines have changed the trajectory of disease, the professional team has become a “Swiss Army Knife” that not only follows the COVID-19 patients but also monitors employees with respiratory symptoms. It also helps connect COVID-19 patients with treatments that must be given early in the course of disease such as monoclonal antibodies and antivirals.

Chaiyachati said COVID-19 forced the health system to expand this kind of monitoring. Learning that it worked is “one of those pandemic dividends that we’ve had.”