Philly clinic gives out more than 1,000 vaccine doses, bridging ‘digital divide’ with low-tech sign-up process, neighborhood locations

More than 1,000 people received a dose of vaccine in the gym at Preparatory Charter High School. It was the fourth such clinic run by Penn Medicine and Mercy Catholic Medical Center.

For weeks, Tyrique Glasgow heard the stories of vaccine frustration from fellow members of the Black community in South Philadelphia:

The clinics that were too far away for someone without a car. The sign-up websites that wouldn’t load fast enough for someone with limited internet access. The appointment slots that were snapped up by people outside the city.

So when he heard about a one-day clinic Saturday in a neighborhood especially hard-hit by COVID-19, he volunteered to be a patient ambassador — spreading the word about how to sign up or, for those who were unable, doing it on their behalf.

By 4 p.m. more than 1,000 people had received a dose of vaccine in the gym at Preparatory Charter High School. It was the fourth such clinic run by Penn Medicine and Mercy Catholic Medical Center, with an orderly check-in process that meant little to no waiting time.

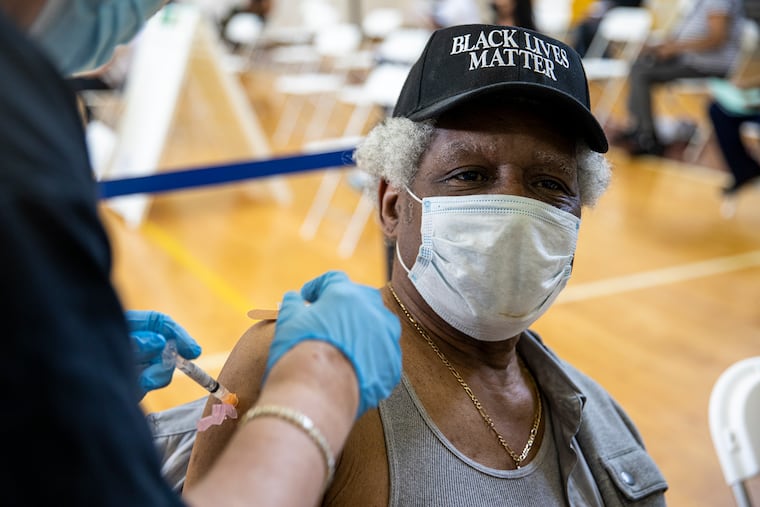

“I am amazed,” said Horace Floyde, 57, who showed up in advance of his 12:30 p.m. appointment, worried about crowds, yet was immediately directed to sit down and roll up his sleeve. “This was so easy I can’t believe it.”

Organizers credited their success to a low-tech sign-up process, allowing people to make appointments by old-fashioned phone call or text message, and to the involvement of community leaders such as Glasgow.

The executive director of Young Chances Foundation, a nonprofit that runs camps and educational programs in the city, Glasgow enlisted volunteers to spread word about the clinic through social media and printed fliers. They also made appointments for older people who needed help.

“This bridges the gap for the health disparities that were in our community even before COVID,” he said.

Floyde, a customer relations specialist for Amtrak, said he had been trying for weeks to snag an appointment through a variety of pharmacy and government websites, to no avail. But when a cousin texted him the instructions to sign up for the Penn-Mercy clinic, it worked immediately, he said.

Dana Hutchins, 46, had a similarly smooth experience.

She had no luck with the pharmacy websites, and was worried about protecting herself as well as the children at the day-care center she runs in West Philadelphia.

Then out of the blue on Monday, Hutchins got a text from coordinators of the Penn-Mercy clinic, whom she thinks had her number from a previous medical visit.

“If you are interested in signing up, text ‘READY,’” the message said.

She did so, and the automated system then guided through a series of steps, confirming her eligibility and securing her consent. She found the explanations to be clear and straightforward.

“It tells you who they are and why they’re doing it,” she said.

At the end, the texting program urges recipients to sign up for a friend or family member, and Hutchins did that, too.

With Saturday’s effort, the Penn-Mercy collaboration has vaccinated 4,000 people. The clinics have become more efficient each time as organizers learn what practices work best, said Phil Okala, Penn Medicine’s chief operating officer.

The first one was in a church, which was a good choice because it was a trusted community location, he said. But the space was somewhat cramped for a mass clinic.

Saturday’s clinic, in the open space of Prep Charter’s gym, was easier. Vaccine recipients picked up yellow “passports” that were printed in advance with their identifying information, then were directed to sit down for an injection as soon as a provider held up a sign saying “Ready.”

Another difference: The first three clinics distributed the two-dose Moderna vaccine, meaning it really was six clinics, as recipients had to come back a second day, Okala said.

But at Saturday’s clinic, providers administered the one-dose vaccine made by Johnson & Johnson. All have been found highly effective at preventing severe disease.

Details on Saturday’s recipients were not immediately available, but in a recent paper in NEJM Catalyst, organizers said 85% of recipients at the first three clinics were Black, with a median age of 65.

Reaching that age group is vital, as its members are more vulnerable to COVID. Yet in the city, most seniors have not yet received a vaccine despite being eligible for almost a month, according to data from the Philadelphia Department of Public Health.

Organizers of the Penn-Mercy clinics think their approach will help address this disparity. In addition to using neighborhood locations and a low-tech sign-up process, they sought to boost vaccination numbers by meeting with faith leaders and other prominent community figures in advance.

The process seems to work, said Kathleen C. Lee, director of clinical implementation in the Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation.

“We’re really trying to embrace the spirit of the community,” she said. “How do we engage friends, family, and neighbors to achieve this mission? It’s really woven into the fabric of how these clinics were set up.”