What is it like to lose your sense of smell? These researchers want to hear from you.

Millions have lost their sense of smell due to COVID and other causes, yet researchers have poor sense of what it's like to live with the condition.

Six years ago, researchers estimated that 43 million U.S. adults suffered some degree of impairment in their sense of taste or smell. Then came COVID-19, adding untold millions to the total.

Scientists have a good understanding of the biology behind many such cases — though the way in which COVID impairs smell is still not fully understood, and effective treatments are few.

But there is one question on which researchers say they are largely uninformed:

What is it like for the patients?

That’s the goal of a new survey led by researchers at the Monell Chemical Senses Center and Thomas Jefferson University, working with the nonprofit Smell and Taste Association of North America.

The 15-minute survey was posted online Wednesday at thestana.org/patient-survey, with the goal of enlisting 1,000 participants by April 20. In just the first day, more than 500 people had filled it out, said Pam Dalton, a Monell scientist who is one of the team leaders.

“There’s never been a comprehensive survey of what people’s experience is,” she said. “You get these numbers out of clinicians. But what is the lived experience?”

» READ MORE: These doctors try to treat COVID smell loss by placing plasma-soaked sponges in the patient's nose

The idea is to involve patients as research partners, not just as subjects to be poked, prodded, and diagnosed. By getting an understanding of patients’ struggles — delays in getting diagnosed, difficulties in finding relief, bottlenecks in obtaining accurate information — team members hope to get a better idea of what they should study, and how, Dalton said.

“We’re seeking a path forward where we can engage people as partners all the way through the research,” she said, “not just as participants.”

The survey, funded by the nonprofit Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, is also open to caregivers and family members who are affected by a patient’s taste or smell loss. Those who complete the survey can enter to win one of 25 $50 gift cards.

Early in the pandemic, the loss of smell was recognized as one of the telltale symptoms of COVID — affecting well over half of patients, by some estimates. Most have regained normal olfactory function without treatment.

But as many as 1.6 million may have experienced smell loss for at least six months, according to a study from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

And as with other forms of smell loss, few effective treatments are available.

Smell training exercises may help some patients. And at Jefferson and Monell, researchers are exploring the use of platelet-rich plasma, a fluid that is extracted from the patient’s blood. Physicians soak bits of biodegradable sponges in the fluid then place them high in the patient’s nose, where they remain for a week before dissolving. Some people have obtained relief, but it is not clear if the plasma deserves the credit. More study is underway.

The new survey will give researchers a better idea of how long symptoms last and their severity.

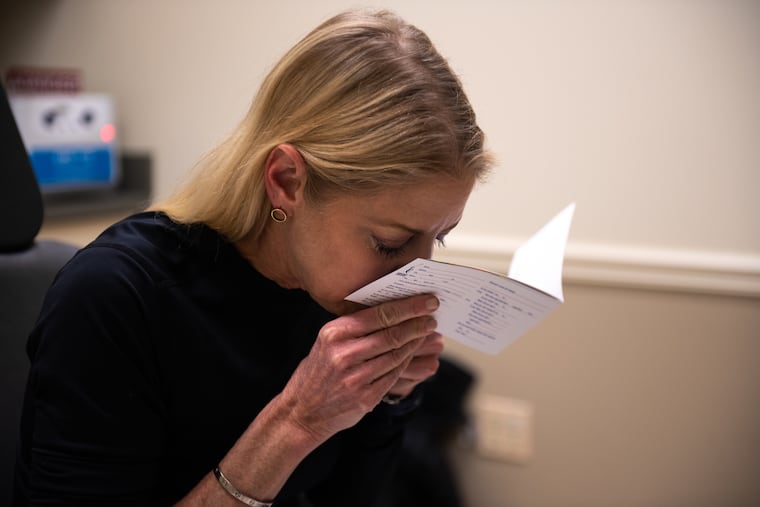

Katie Boateng, a project co-leader and president of the Smell and Taste Association of North America, has a personal interest in the outcome.

She lost her sense of smell in late 2008 or early 2009, the apparent result of a viral infection.

The loss of smell has a variety of health consequences, she said. It can disrupt healthy eating habits, either by causing people to eat too little of the right foods, or too much of the wrong ones — favoring sugary, fatty foods in search of an elusive olfactory reward. It can harm mental health. And it can place the person at risk of physical injury — say, if they are unable to smell a gas leak or smoke from a fire.

“Smell and taste disorders are invisible disorders,” she said. “For some people, they can handle it and move on. For others, it’s devastating.”