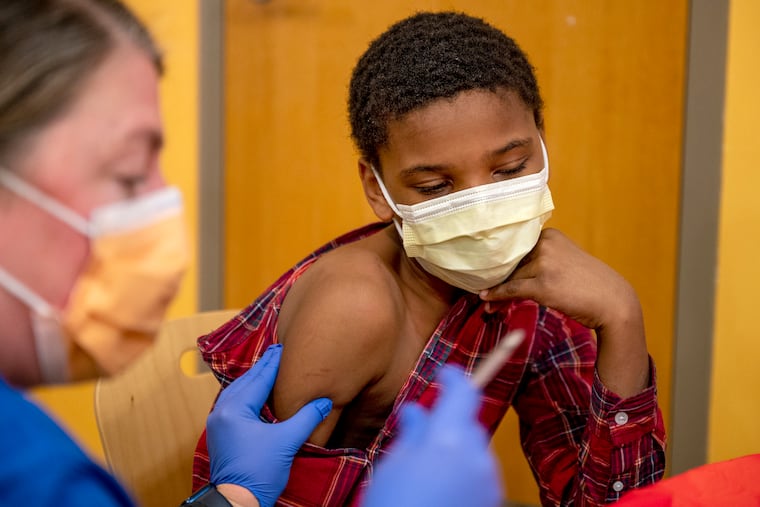

Philly vaccination rates for Black and Hispanic children lag, even as another COVID-19 surge looms

As had been the case with previous waves of vaccination, doses going to young children in Black and Hispanic populations are lagging. Experts think that trend can be reversed.

About 21% of Philadelphia’s eligible children have received a COVID-19 vaccine more than a month after the 5-11 age group was approved. The low rate worries health experts as the holidays approach and omicron surges.

Meanwhile, repeating a pattern seen earlier in the vaccination effort, Black and Hispanic populations are lagging behind other groups. Among 5 to 11 year olds, just 8% of Philadelphia’s Black children and 12% of Hispanic children have received at least one dose, according to city data. About 24% of white children and 31% of Asian children have received at least one dose since the vaccine was approved for younger children at the beginning of November. As of Monday, 18,540 Philadelphia children ages 5 to 11 had received their first vaccine dose.

“I think it’s unacceptable,” said Ala Stanford, a pediatric surgeon and founder of the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium and the Ala Stanford Center for Health Equity.

Statewide, about 18% of 5 to 9 year olds are vaccinated, and 35% of 10 to 14 year olds, the age groups for which the state provides data. The state does not provide data about the race of children vaccinated.

In Philadelphia, school officials anticipated that Black and Hispanic children would have lower vaccination rates and have tried to compensate by hosting clinics and providing information for parents.

“The vaccination rate in the BIPOC community is lower, and we know that, and we’re working hard on that as a community,” said Barbara Klock, the School District’s chief medical officer.

Others, though, say schools’ potential as a vaccine provider has been underutilized, and, even after a year of vaccination, accessing doses remains confusing and challenging for some.

“I’m concerned,” Stanford said. “I think we’ve got to buckle down.”

Unvaccinated children are more likely to carry and spread the virus, physicians said, posing a risk to relatives who are older or have health conditions that could make them susceptible to more serious cases of COVID-19.

“We’re doing these vaccinating of the kids more to protect the elders in the family,” said Jose Torradas, medical director of Unidos Contra COVID, a regional organization working to boost Hispanic vaccination rates. “There is also the benefit to kids in terms of not even showing symptoms or getting sick at all.”

Kids rarely experience severe illness from COVID-19, though 655 children have died because of COVID-19 related illness, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About two-thirds of those deaths were among nonwhite children, according to the COVKID project, a site focused on the pandemic’s toll among children.

A 17-year-old Philadelphia girl died last week after contracting COVID-19.

» READ MORE: Alayna Thach’s family speaks about COVID-19 death of 17-year-old: ‘How is this possible?’

Outreach from groups like Stanford’s, hospitals, and the Philadelphia Department of Public Health have made inroads building trust among Black and Hispanic communities. BIPOC populations often are less connected to the health-care system for reasons that include poverty, lack of transportation, and distrust of health-care systems due to a history of mistreatment and racism. With 69% of Hispanic Philadelphians receiving their full course of doses, the group is the second best vaccinated in the city overall, after Asians. That population’s vaccination rate is so high due to Asian advocacy groups and the city coordinating clinics in Chinatown and providing multilingual resources. Black vaccination rates, now at about 61%, have steadily increased since this summer. About 63% of white Philadelphians are vaccinated.

Philadelphia’s communities of color have been initially hesitant toward getting vaccinated, but results of the vaccination efforts show this reluctance can be countered through conversations and answering questions, health care experts said.

“It’s education, it’s time, it’s trust building, and that’s what we were seeking to do,” Stanford said. “And it’s also being permanent and consistently present.”

That process, though, had to start all over again to encourage parents to vaccinate young children.

“You can’t assume that ... what people did for themselves they’ll do for their children,” Stanford said, noting that parents can be additionally hesitant when it comes to their children. “A parent is going to do everything they can to protect their child.”

Among Hispanic families, Torradas said, there remain language barriers to overcome. Emphasizing the obligation to protect relatives through vaccination has proven motivating among Hispanic communities, he said. It’s a message he’s now sharing with children.

“We’re not shy even talking to the young kids as to the collective movement or sacrifice that is getting vaccinated,” he said.

» READ MORE: Latino Philadelphians are getting vaccinated more quickly than any other group. It hasn’t been easy.

Bettina Polite, of North Philadelphia, had no hesitation about getting her children vaccinated, she said at a clinic hosted by the Philadelphia Zoo on Dec. 14, where she got a booster and her two children got their first doses. Her son, Jordan Polite-Garner, 11, has already had to quarantine this school year due to exposure to COVID-19, she said.

“This is put in place as a safety measure for our children and ourselves,” she said of the shots, “so it has to be done.”

Almost 300 children and adults received shots from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia staff at the zoo. The administration of shots was occasionally punctuated by the screams of children reacting to the sight of needles, not to actual pain.

“He didn’t even know he got the shot,” said Kia Johnson of her 7-year-old son, Hunter.

The School District has been hosting clinics since November, and has seen strong demand for doses, said Sage Myers, medical director of CHOP’s community vaccination program, who has coordinated with the district’s clinics. The district notifies parents of vaccination events through robocalls and texts, officials said.

“A lot of times we’ll get a huge bump when the School District sends out a text” to parents, Myers said, “which tells me those people aren’t against getting vaccinated. It’s finding the right place and the right time.”

The district has scheduled 35 vaccination clinics since November, a spokesperson said, with one scheduled Tuesday and another Jan. 5.

The district approached the Black Doctors COVID Consortium to organize clinics, Stanford said, and initially she wanted to set up clinics at a single location and stay there for a week to give time for word to spread. An adjusted proposal the consortium sent the district on Oct. 6 described a plan to host clinics for 5 to 11 year olds at schools on Mondays through Saturdays from Nov. 8 to 20. She estimated the consortium could vaccinate 100 students an hour from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. each day.

So far, though, the plan hasn’t moved forward.

“We had time to really go hard. We were prepared to do that,” she said. “This is the bureaucratic stuff that holds up implementation.”

The School District did not respond to questions about why Stanford’s proposal wasn’t implemented, but Klock noted the district already has five health systems it is collaborating with for vaccination clinics.

There is no one source parents can tap for information on every vaccination resources in the city. The Philadelphia Department of Public Health maintains an online clinic schedule, but that doesn’t include clinics organized through the School District, which it posts on its own website. It also doesn’t account for all the clinics being organized by hospitals and health care organizations citywide.

Health Department spokesman James Garrow recommended people visit phila.gov/vaccine and vaccines.gov to find sites.

“It would be our preference to have everything in one place,” Garrow said, “but we don’t have the capacity to develop a tool to manage all of the clinics, force clinics to update us on their hours and locations, and maintain it through frequent changes.”

Stanford urged vaccine providers to set up mass clinics for children providing shots at the same location daily.

“Monday through Saturday, and do it until our [vaccination] rates go up, that’s what I would propose,” she said. “This fragmented system is not going to help.”

The clinic at the zoo was preceded by targeted outreach to the schools and CHOP patients nearby, said Myers. Two of the three least vaccinated zip codes in the city are near the zoo. It’s been discouraging, she said, to see, despite efforts this year, the same race imbalances emerging among young children as have plagued the vaccination effort all year.

“I wish that we would see that as we put these in place and we try to be more cognizant of it,” she said, “we could see that initial disparity lessen.”