Can a drug stop Alzheimer’s before it starts? Penn is part of an international trial for people aging without symptoms.

People in the trial have abnormal proteins in their brains, but they have yet to see any decline in cognitive ability.

Like many people above a certain age, Tony Kenneff occasionally forgets the right word for something, or why he went into a room, and he worries.

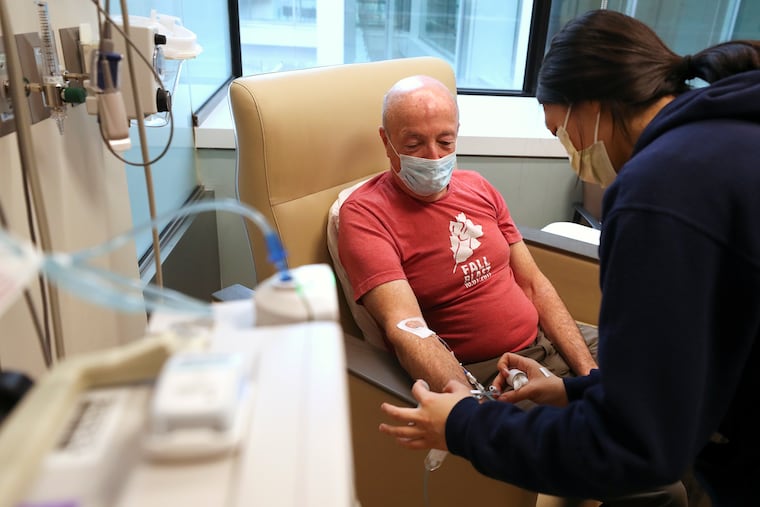

His 71-year-old brain is working just fine, as far as physicians at the University of Pennsylvania can tell. Yet every other week, the Lancaster County man undergoes an hour-long infusion that may rid his brain of abnormal proteins associated with Alzheimer’s.

The treatments are part of an international trial that aims to stop the debilitating brain disease before it starts.

Previous drugs designed to clear these telltale proteins, called beta amyloid, have failed or yielded mixed results. But the one in Kenneff’s trial, called lecanemab, already has proven modestly beneficial for patients in the early stages of Alzheimer’s, and may be approved for such patients sometime in 2023. The hope is that if the drug is given even earlier — to people like him, with no outward symptoms — it will ward off the disease for years.

Some physicians remain skeptical. And should the drug be approved by the FDA, policy experts warn that the health-care system is ill-equipped to treat the millions who would be eligible.

Kenneff, who signed up for the trial because he has an elevated genetic risk of Alzheimer’s, said an aging society can’t afford not to try.

“A Manhattan Project type of thing for Alzheimer’s is what we need,” the retired postal service worker said.

» READ MORE: What to know about the new drug trial for Alzheimer’s

Sticky proteins

Half of the trial participants receive infusions of the drug for four years, and half get a placebo, though no one is told which.

The drug consists of customized antibodies that recognize and bind to the telltale, sticky proteins that accumulate in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s, enabling the immune system to remove them. But when similar drugs have been tested in the past, clearing away the proteins has not translated to an improvement in symptoms.

There are several theories as to why. One is that the proteins don’t actually cause the disease, but are more of a signal — like smoke from a fire. Another is that the proteins are not the only cause, and that a truly effective solution requires tackling all of them. A different type of protein, called tau, may be a bigger culprit, according to research by prominent Penn scientist Virginia M.-Y. Lee.

Almost certainly, a key reason that past efforts to treat Alzheimer’s have failed is that they started too late, said neurologist Sanjeev Vaishnavi, who is overseeing the portion of the new trial taking place at Penn.

“By the time people have significant symptoms, and they already have a lot of damage in their brain, it’s unlikely we’re going to stop or reverse that process,” he said.

So in order to qualify for the new trial, volunteers must score within the normal range on a series of cognitive tests — even though their brain scans show that the buildup of amyloid already is underway. Trial coordinators hope to enroll 1,400 volunteers aged 55 to 80 at more than 100 locations worldwide.

Finding a risk factor by accident

Kenneff’s path to enrolling in the study began by accident. Seeking to trace his Irish ancestry, he submitted his DNA to the 23andMe genetic testing service, and learned he was at increased risk of Alzheimer’s. He submitted his name to a database of people willing to participate in research, and eventually was contacted by Penn.

It turned out he had one copy of a gene mutation called APOE4, which more than doubles the risk of Alzheimer’s.

Kenneff’s infusions began in August 2021 and will continue for three more years. He also undergoes periodic cognitive tests, such as listening to lists of words and repeating back as many of them as he can.

Starting next summer, the infusions shift from every two weeks to a monthly schedule, but it’s still a big time commitment. If the drug were to be approved, it is hard to imagine how it would be administered on a wide scale, Kenneff said.

“It’s not like you can just go to the pharmacy and get a prescription,” he said. “It’s people going there and sitting for an hour to get this infusion.”

That’s a valid concern, as millions of people have elevated levels of amyloid in their brains, said Jakub Hlávka, a health-policy scholar at the University of Southern California.

“Even in the best-case scenario, it will take years before all patients eligible currently will be able to get treated,” he said.

Costs into the billions

Then there’s the cost. The scans used to detect the abnormal brain proteins run into the thousands of dollars, and the drug itself is expected to be priced in the tens of thousands, said Hlávka, a fellow at USC’s Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics.

“It will result in a possibly existentially large budget impact for most payers,” he said, “amounting to billions of dollars in the United States each year, if not tens of billions.”

Physicians also are wary of the kind of uncertainty that surrounded the last such drug. In 2021, the FDA approved a different antibody-based drug for Alzheimer’s, called Aduhelm, despite mixed evidence that it worked, and Medicare officials later declined to cover it for most patients.

Safety is another unanswered question with lecanemab, the new antibody that’s being tested at Penn and more than 100 other sites. Possible side effects of the drug include brain swelling and bleeding, which generally can be managed with medication.

In an earlier trial of lecanemab, for people who already had symptoms of Alzheimer’s, one person died after experiencing brain swelling and bleeding, according to a report from Science magazine. The drugmaker Eisai, based in Tokyo, did not disclose whether she received the drug or a placebo, and it has said no deaths in the trial are attributed to the drug.

Weighing the risks in a trial

Kenneff thinks the potential side effects are worth the risk. Though he doesn’t know whether he’s getting a placebo or the real thing, he hopes his participation will yield answers for others, including family members who may have the same genetic predisposition that he has.

In the meantime, he engages in an activity known to boost brain health: exercise. He uses a stationary bike, a treadmill, and a NordicTrack machine at his home in Manheim. He also runs after his 16 grandchildren.

Periodically, the researchers also solicit an assessment of each participant’s function from a designated friend or relative. In Kenneff’s case, it’s his wife, Doris, 62.

One recent appointment was a source of humor — and hope. Separately, both Kenneffs were asked to recall the details of a family occasion from the last year, and the husband and wife remembered it differently. Uh-oh.

Except when Tony Kenneff quizzed his wife afterward, she agreed that her memory of the event was wrong, not his.

“She said, ‘Oh yeah, I had that wrong,’” he recalled.

If his memory is at least as good as someone nine years younger, Kenneff thinks he’s in good shape. And if it turns out he was treated with the drug, he hopes it will allow him to remain that way.