Mütter Museum visitors can now see library with histories of epidemics, herbal remedies, and anti-vaccine sentiment

On weekends, museum visitors can see the library's rare treasures for the first time in its 234-history.

The Mütter Museum hails its “disturbingly informative” collection of old bones, body parts, and other medical curiosities that tend toward the macabre.

But hidden away on the upper floors of its red-brick building is a multimillion-dollar library of rare medical archives, photos, and books from centuries past, when early physicians tried to solve the mysteries of the human body with none of the tools of modern science.

Within the Historical Medical Library are thousands of items with perhaps less shock appeal, but every bit as much value to the history of medicine.

The collection is now open to the public for the first time in its 234-year history, included with weekend admission to the Mütter Museum downstairs. Saturday and Sunday marked the library’s official public opening, though a “soft opening” has been ongoing since June.

Visitors can read yellowed archives from Philadelphia’s battles with yellow fever in the 1790s. Gilded medieval manuscripts complete with recipes for herbal remedies. Pamphlets tout the use of mercury, opium, and other old treatments of questionable benefit.

Once restricted to researchers, the library was judged by its overseers as too valuable not to share with the public, director Heidi Nance said.

A prime example is the library’s collection of anti-vaccine materials, she said. For any who imagine that attacks on vaccines are a recent phenomenon, the library has ample evidence that they’ve been around since the 19th century.

“One of the ways we understand today is by understanding history,” Nance said. “How did we get here?”

The library is not part of the Mütter Museum, but is a sister organization. Both are under the umbrella of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

Among the library’s treasures are more than 400 books printed before 1501, the oldest of which was written in the 13th century. Most are stashed away in the library stacks covering more than 51,000 linear feet of shelf space on seven floors. The public has access only to the library’s reading room, which features a rotating display of highlights.

Among featured items is one that should appeal to Harry Potter fans. In a replica of a medieval illustration, a man is shown running away after he digs up a magical mandrake root. According to lore, the plant could emit an ear-splitting scream, as Potter fans know from reading about herbology class at the Hogwarts School.

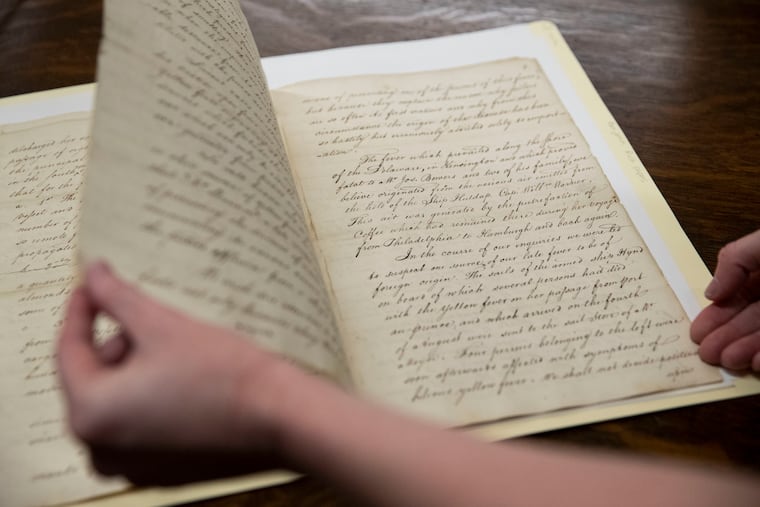

Nearby is a handwritten 1797 report on yellow fever, in which prominent Philadelphia physicians blamed the spread of disease on “putrid exhalations from the Gutters, Streets, Ponds and Marshy Grounds.” Well, sort of. The disease is transmitted by mosquitoes, which breed in ponds and other stagnant water, but that link was not discovered until nearly a century later.

Visitors also can see a 1915 handbill that describes Apetol, a purported appetite-enhancer, under the headline “It Will Make You Eat!” More than a dozen herbal ingredients are listed, said to achieve their effect through “superior pharmaceutical manipulation.”

Other treasures include a medical text made from palm tree leaves bound with string, written in the 18th century in what then was called Ceylon (now Sri Lanka).

Vintage photos include one from the early 20th century, showing a horse-drawn buggy with a banner advertising an herbal “blood purifier.”

“This was not vetted by the FDA,” Nance said.

Though much of the early medical history in the collection will seem like snake oil to a modern audience, much of it has stood the test of time.

Among the artifacts is a medical bill from 1800, in which a man was charged three pounds to have his child vaccinated against smallpox. A descendant of that vaccine is being used this year to inoculate people against a related illness: monkeypox.

Most of the library’s materials were written by men, given that women were prevented from training to become physicians for much of medical history. Yet women still practiced medicine, as shown in the library’s early 20th-century “commonplace book” from prominent Philadelphia-area suffragist Juliet Coates Walton.

The volume includes medicinal recipes for treating wasp stings, warts, rheumatism, and the common cold. For the latter, Walton’s recipe called for a mixture of ammonium chloride, licorice, and sugar, dissolved in hot water.

One album was open on Sunday to a series of black-and-white photos from the now-defunct Philadelphia General Hospital. In one image, white-coated physicians demonstrated how to deliver a baby, hovering over a bedridden actor who pretended to be in labor.

The actor, Nance noted with glee, was a man, even though some nurses were in the audience and presumably would have been able to portray the experience more faithfully.

“I think it’s hilarious,” she said.