Public health quarantines have a history in Philadelphia | 5 Questions

Quarantine in the 19th century was a major pain, and it still is in the 21st century.

A highly contagious disease was spreading quickly. People were getting sick and dying, with no vaccine and little knowledge of how to treat it. Ultimately, public health officials ordered Philadelphia residents to quarantine.

This was not 2020. It was 1793, when yellow fever entered Philadelphia through its ports and spread wildly, killing 5,000 people in less than three months.

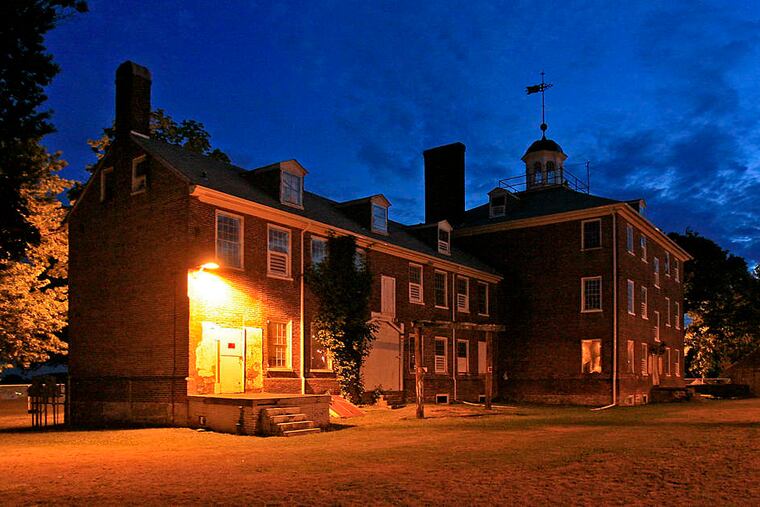

But urging residents to quarantine or temporarily relocate wasn’t enough. The city built the Lazaretto, a large brick facility named for the patron saint of lepers, where people and goods arriving by ship were screened and quarantined if suspected of illness.

» READ MORE: Long before coronavirus, Philly ran a quarantine center for another deadly contagion

The Lazaretto closed in 1895. But more than a century later, in 2005, the building and its rich history caught the attention of David Barnes, an associate professor in the Department of History and Sociology of Science at the University of Pennsylvania. He became fascinated by its stories. This month, Johns Hopkins Press is releasing his third public health history, Lazaretto: How Philadelphia Used an Unpopular Quarantine Based on Disputed Science to Accommodate Immigrants and Prevent Epidemics.

Today, the building houses the government offices of Tinicum Township. In the halls where patients once suffered with their fevers and digestive maladies, people are paying property taxes and filing their code applications.

We spoke to Barnes recently about the lessons of the Lazaretto.

What are some of the most striking similarities between then and now?

There’s a recurring dynamic in many epidemics that almost transcends the specific circumstances of each disease. In the earliest stages, there is uncertainty and a vague sense of fear, followed by some combination of official denial or silence or release of only fragmentary information or contradictory information. This, in turn, intensifies the uncertainty and fear. It breeds mistrust, which builds to some kind of panic.

People who have the ability to leave population centers and go someplace remote will do so. And then you see a flood of patients to health-care facilities, even patients who might not even have a severe illness, but are just terrified and experiencing this general sense of desperation.

Quarantine was criticized as tyrannical and absurd. Yet when disease spread from Front Street into the rest of the city, an outraged public called for accountability.

Yes. Quarantine in the 19th century was a major pain, and it still is in the 21st century. Quarantine caused acutely inconvenient delays for sailors and passengers who were so close to their destinations. But especially, quarantine was bad for business. Time was money, and it still is. With any delay, merchants ran the risk of losing customers who would seek their goods elsewhere, and of losing perishable goods outright to spoilage. But here’s the kicker: There’s only one thing worse for business than quarantine, and that is an actual epidemic. You want to see businesses suffer, try letting yellow fever break out in your city. That, I argue in the book, is a big reason everyone complained about quarantine, but almost no one went so far as to advocate abolishing it.

What about the unfairness of outbreaks? What about those too poor to heed the advice of the 1800s, which was to “leave quickly, go far away, and return late?”

In the 1793 outbreak, 40,000 residents fled Philadelphia. Of the 20,000 who remained, one in four died. Guess which group was wealthier.

I hear all the time that germs don’t discriminate and that epidemics are the great equalizer. It’s not true today, and it never has been true. Poor and marginalized populations have always suffered disproportionately from infectious disease. This is true not just in terms of higher rates of illness and death, but also in terms of disease-related stigma that intensifies already existing discrimination and fear.

We also saw this greater vulnerability at the Lazaretto with the thousands of destitute and hungry immigrants who arrived desperately ill with typhus (called “ship fever” at the time).

How do we address these inequities?

It is a huge challenge. We can start with the obvious things, which shouldn’t be controversial, like providing everyone access to basic lifesaving care. This doesn’t always mean expensive, high-tech care. Sometimes it can just be basic nursing care. We should provide that to everyone, regardless of income, status, race, or any other aspect of identity.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned from studying the history of public health, it’s that we can never medicate our way to a healthier population. We can use pharmaceuticals to save lives in an emergency, but they’re never going to make populations healthy. Populations get healthier when we reduce the factors that weaken their resistance to disease. These include poverty, unemployment, malnutrition, food insecurity, housing insecurity, chronic debilitating stress, substance abuse, and many others.

What are the differences in quarantine between then and now?

We don’t have Lazarettos — separate, isolated facilities where we make people and ships and goods wait for an undetermined period of time before entering the city. With COVID, we had semi-voluntary individual Lazarettos in our own homes. But the sense of inconvenience, the sense of frustration, the sense of disruption of the rhythms of life and business relationships and personal relationships, that was as true then as it is now.

Quarantine, especially as practiced in the 19th century, was a blunt instrument. Today, we have sharper instruments available to us to prevent various diseases or minimize their spread. We can test for the presence of specific germs in people and places. We can tailor our limitations on movement and behavior to fit what we know about those germs and diseases. Clearly, in the case of COVID, the shutdowns and limitations on public interactions were necessary. And they caused a lot of harm.

Now, as it was in the days of the Lazaretto, our challenge is to minimize the harm and maximize the benefit.