The Texas shooter was bullied. That has Philly’s gun violence experts talking about ‘unaddressed pain’

The perpetrators of violent crime have often been victims themselves, which experts describe with the catch-phrase — “hurt people hurt people.”

A boy was bullied for his stutter and a strong lisp. Reclusive at school and living in an unstable home, he began skipping classes. Family and friends would later say he started displaying violent behaviors, such as getting into fistfights and cutting his own face.

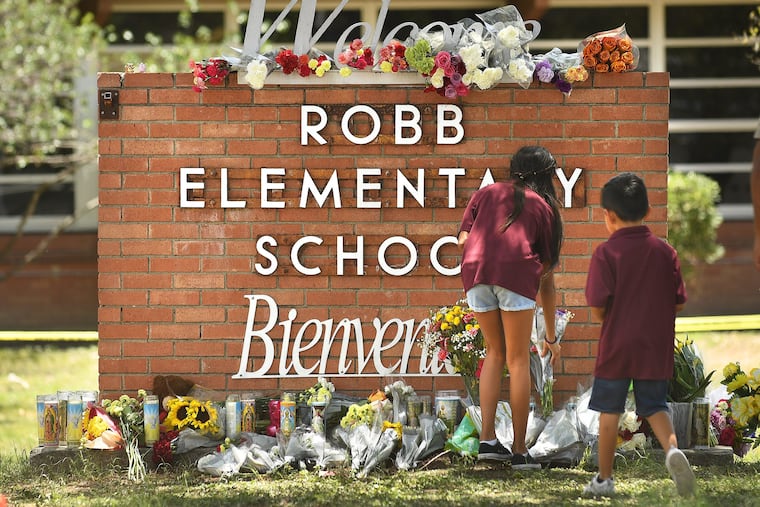

Bullying takes place all the time, all over the country — and only rarely does the experience play into a mass casualty shooting such as the one seen this week when authorities say 18-year-old Salvador Rolando Ramos stormed an elementary school near his home in Uvalde, Texas, with an assault rifle, killing 19 children and two teachers.

» READ MORE: Gunman in Texas school shooting was bullied as a child and grew increasingly violent, friends say

Yet it is common for the perpetrators of violent crime to have been victims themselves. Experts in violence prevention have a catchphrase — “hurt people hurt people” — and see the consequences playing out daily in Philadelphia’s epidemic of gun violence outside schools. Already this year, more than 70 children under the age of 18 have been shot in Philadelphia. Of those, 12 were killed. The resulting trauma will affect their loved ones and those who witnessed the violence.

Horrific events like the latest school shooting focus attention on a complex dynamic. According to an analysis of 57 school shootings published in the Journal of Social Psychology last year, nearly half of the shooters reported a history of rejection, which they often described as bullying.

Peter Langman, an Allentown psychologist who studies school shooters and has served on national and Pennsylvania task forces focused on violence prevention, cautioned that the relationship is nuanced. Bullying — or any other trauma — alone cannot explain mass shootings or predict violence.

“Most students who are picked on never commit a school shooting, but some school shooters do have a history of significant peer harassment,” he said.

A similar dynamic factors into Philadelphia’s gun violence, and experts say addressing past trauma is key to prevention.

“It’s rare that an offender wasn’t a victim previously,” said Hannah Klein, assistant professor of criminal justice at Lewis University in northeastern Illinois, whose research focuses on Philadelphia. The victimization doesn’t have to be a past shooting but “can be anything from abuse to violence, being beaten up, being involved in fights in the street,” she said.

In academic literature, this phenomenon is known as the “victim-offender overlap,” Klein said. One study published in the academic journal Criminology, for example, found that victims of violence are 55% more likely than non-victims to commit a violent crime.

Unaddressed pain

Roz Pichardo, a Kensington resident who runs the antiviolence campaign Operation Save Our City, channeled her own experiences with violence into efforts aimed at healing.

Her brother was murdered in 2012, and she herself survived an attempted murder in which she lost her boyfriend. Pichardo said that the man who took her boyfriend’s life was an ex-boyfriend who also was a victim of violence.

“I see so much devastation, and a lot of times it comes from unaddressed pain,” she said. “If we don’t have conversations with people, then they can act on it.”

A 2019 CDC survey found that 14% of Philadelphia high school students reported being bullied on school property — with rates similar among white, Black, and Hispanic children.

Reuben Jones, executive director of Frontline Dads, a violence prevention organization in Philadelphia, said words such as abuse, addiction, and poverty often come up in his conversations with at-risk youth. But the teens that he talks to, who are mostly Black or from communities of color, rarely use the word bullying.

“Bullying connotes some sort of weakness — like you allow someone to harm you or take advantage of you in some way,” Jones said. “Even in situations when it happens, they don’t necessarily use the label bullying.”

He says that teaching peaceful negotiation techniques can give teens skills to navigate heated situations.

Sandra Bloom, a psychiatrist and professor at Drexel University’s School of Public Health, said trauma, especially in the adolescent brain, can make it hard to process information quickly in a moment of threat.

When a teen also has access to a gun, she said, the result could be a pulled trigger before the consequences are considered.

“There is no judgment involved yet — afterward there might be, but it’s too late,” she said.