At N. Philly children’s hospital, conference addresses trauma that causes gun violence

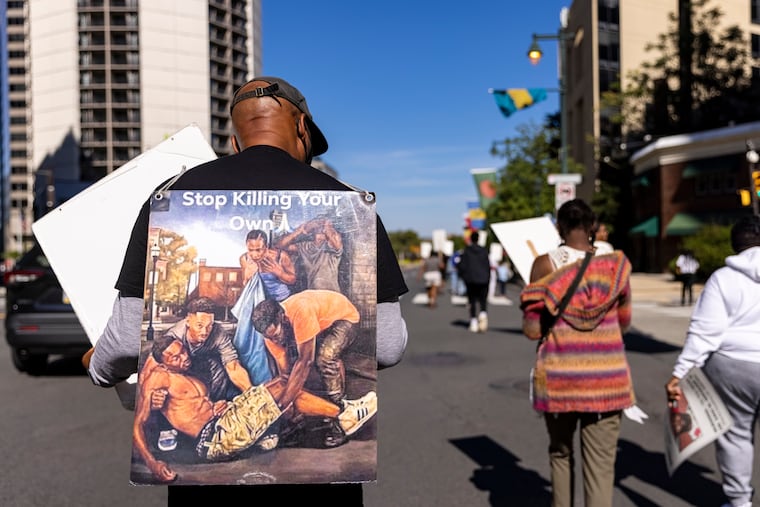

Philadelphia's grassroots anti-violence organizations exchanged ideas on how to stem the city's gun plague.

Experts and community organizations gathered Friday to discuss tools to address Philadelphia’s gun violence crisis, just days after the city marked its 400th homicide of the year.

Solutions raised included counseling, mentoring, support for children, and assistance for people recently released from prison.

One approach brought up sparingly was law enforcement.

“The work that we have to do to prevent gun violence in our societies is a larger role of prevention at every level,” said Roger Mitchell, chief medical examiner and interim deputy mayor for public safety and justice for the District of Columbia. “We have to do the work of improving our communities in every aspect … education, economics, housing, and health care, and criminal justice.”

Mitchell was keynote speaker at a conference focusing on gun violence prevention hosted Friday by St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children, and he highlighted the event theme of putting gun violence into a health care context that law enforcement alone can’t solve. Gun violence is borne of trauma caused by racist societal structures, Mitchell said, and causes trauma that perpetuates shootings and death. Addressing that cycle is necessary to reducing violence.

“Racism is so pervasive. … It’s so important for us to understand these structures have been in place for decades,” Mitchell said. “There needed to be prevention and programming and curriculum development at every level.”

» READ MORE: Intersections of Injustice

A recent Inquirer report highlighted how gun violence disproportionately plagues communities already experiencing inequities, including poverty, housing insecurity, and health access. It noted some of the city’s most violent neighborhoods are also those that were historically discriminated against by racist lending practices. Another Inquirer story highlighted how the pervasive fear of shootings in parts of the city eclipsed even COVID-19 as a threat to communities.

The conference featured about two dozen speakers from groups throughout the city who described community efforts that can make an impact.

Stanley Crawford described his internal battle to keep violence from begetting violence. When his 35-year-old son was slain in 2018, leaving behind five children, he considered a retribution killing, he said.

“They did not just kill my son, they killed relationships,” he said. “They didn’t just take that body off the planet, they took those relationships off the planet.”

Instead, the 69-year-old founded Black Male Community Partnership of Philadelphia with the hope that community elders like himself could serve as role models for at-risk young adults in the Black community.

“We’re not out there amongst them to engage with them,” he said, “and they’re very receptive to the wisdom of the unc or OGs.”

Speakers described a bleak reality that fear of guns is leading to more people carrying guns.

» READ MORE: For some Black men and teens in Philly, relying on guns has become commonplace

“For my age group it’s get up, grab your bookbag, your gun, and your keys,” said Kizmeck Allison, 20, who lost a cousin in a shooting and is a participant in the youth counseling program Youth Empowerment for Advancement Hangout (YEAH). “It’s like a normal thing. It’s like a pair of shoes or socks.”

YEAH offers tools like peer mediation and therapy for teens and young adults experiencing gun violence with an emphasis on the Black community, said Kendra Van Der Water, cofounder of the group. Allison described experiencing depression, anxiety, and crippling shyness that stemmed from the stress created by gun violence.

“That’s a hurt that you can’t get rid of and you can’t take it out of your head,” she said. “It’s like it’s permanent, it’s like a nightmare.”

Several speakers outlined efforts to reach young people who are at risk of committing violent crimes, particularly those who are enmeshed in the drug or gun trade.

Tonie Willis, who runs the North Philly housing nonprofit Ardella’s House, helps women recently released from prison boost their self esteem. Relationships with the wrong people, she said, can lead to women acting as gun buyers for boyfriends who then use the weapons to commit crimes. If the gun is recovered, the woman’s role as a buyer leads to criminal charges against her, too.

“They chose the wrong person to love,” she said. “It’s so important to talk to people about not doing straw purchases for people.”

Carl Day, pastor of Culture Changing Christians Worship Center in New Jersey and Philadelphia, said it’s important to let people know they have other options in life.

“I ask questions because oftentimes it stirs them up, or it finally gets them to think differently,” he said. “A lot of times nothing new can come from them because they’re talking about the same old things.”

What can prove helpful, he said, is removing people from the environment where they feel pressure to conform to their peers’ attitudes. He hosts retreats that give people space to say things they may not share with peers.

Collectively, the speakers represented an array of approaches that sought to address the social determinants of health — such as access to education and health care — that contribute to gun violence. What’s lacking, they said, are resources.

Group leaders said demand for services overwhelms their capacity.

“We do have certain types of resources around,” said Chantay Love, who founded Every Murder is Real in honor of her brother who was killed 20 years ago and provides therapy for trauma victims, “but is it enough? Absolutely not.”