Ahead of a divisive election, this Penn doctor is working to ensure people with dementia can vote

Voting in long-term care is changing for everybody this year.

Jason Karlawish’s interest in ensuring that Americans with dementia can vote goes back 20 years to another contentious election, the one between George W. Bush and Al Gore that made the “hanging chads” on Florida ballots famous.

Chads aside, Karlawish realized that the confusing ballot design led people with perfectly fine brains to make mistakes. A doctor who treats Alzheimer’s patients and is codirector of the Penn Memory Center, Karlawish wondered what voting had been like for people with cognitive impairment.

Around the same time, he talked about voting with a group of caregivers for the center’s patients. Some said a patient shouldn’t vote if he doesn’t understand the election. Some gave help when needed. Others said they voted for their loved one.

Karlawish saw a fascinating, multidisciplinary topic that had barely been studied, so he jumped in. He learned that people with dementia have the legal right to vote but are often disenfranchised by professional or family caregivers who decide they’re not capable of making good decisions. The law, he said, doesn’t care whether you can make good decisions. In 2008, he worked with the American Bar Association on a pilot program in Vermont that helped people in long-term care settings with dementia vote.

That laid the groundwork for a new guide produced by the Memory Center and the ABA Commission on Aging. It explains how caregivers can help voters with dementia and other forms of cognitive impairment.

In this highly charged election year, the guide is important for a generation that often takes voting very seriously. “Persons living with dementia are citizens and they need to have their rights respected just like everyone else’s rights,” Karlawish said.

In a study of the 2007 Philadelphia mayor’s race, Karlawish found multiple ways that long-term care residents with dementia were kept from voting. Staff didn’t get around to finding out whether residents were registered or wanted to vote. Sometimes staff would decide on their own that a resident didn’t know enough about the candidates or couldn’t remember enough. Asked if the situation has improved, he said: “I don’t think Philadelphia’s made a good effort to go out into long-term care facilities.” He would send bipartisan teams of election officials.

Charles Sabatino, director of the ABA commission, said recent elections illustrate the importance of each vote. “We’ve had very major experience with votes being determined by very narrow margins," he said. "To the extent that any group or subgroup is impeded from voting, that could determine the outcome of an election.”

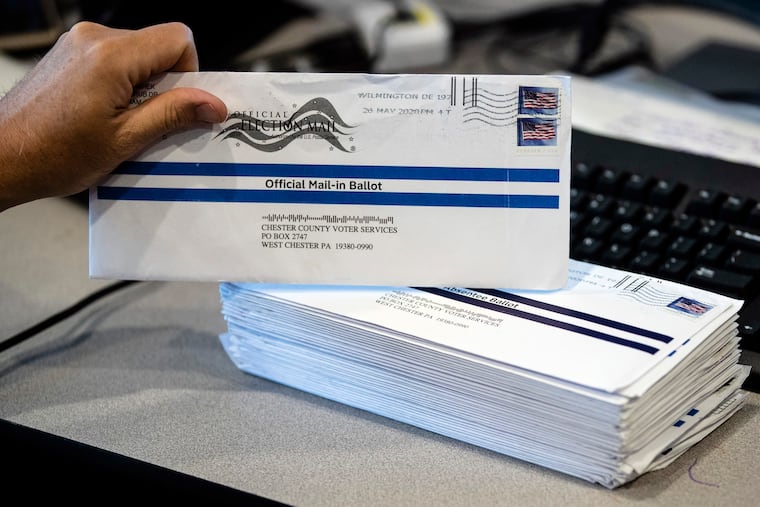

While many with dementia live at home where family members can help them fill out ballots, others reside in long-term care settings that were devastated by the first wave of coronavirus in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Independent residents now have more freedom to come and go and visitation is easier, but restrictions remain.

Zach Shamberg, president and CEO of the Pennsylvania Health Care Association, which represents long-term care facilities, said many of his organization’s members were polling places before coronavirus. That made voting easy for all residents but is too dangerous now. Facilities are now helping residents apply for mail-in ballots and, when needed, fill them out. Asked if centers can do this while also coping with the extra work the coronavirus has caused, Shamberg said: “It’s all about leadership within the facility.”

When Daniel Kaye started his job as director of life enrichment and community engagement at Rydal Park, a Jenkintown retirement community, seven years ago, residents asked him if Rydal Park could become a polling place. Then they wouldn’t have to take a bus to a car dealership to vote. After that happened, voting rose from around a dozen residents to 300.

This year, Kaye is working with a steady stream of residents who want to vote by mail. Very few will vote in person. For residents with cognitive impairment, the staff just asks if they want to vote. “They still will watch TV. They know the parties,” Kaye said. “They know if they have a candidate they like.”

Interest in voting is very high. “I would say it is the top subject every day with us,” Kaye said.

Regina Farrell, vice president of health center operations at Meadowood Senior Living in Worcester, said social workers have been spending more time with residents anyway since the pandemic to prevent isolation, so it hasn’t been hard to help residents with dementia sign up and vote.

So far, 21 of 32 personal care residents and 27 of 54 in Meadowood’s nursing home have requested help with mail-in ballots. Others may have received help from family members.

The new guide provides simple voting rules. People with cognitive impairment need to say they want to vote and they need to make their own choices. Sabatino said families can discuss politics earlier but not during the voting. At that point, helpers can only read what’s on the ballot. They can say whether a candidate is Republican or Democratic if that’s on the ballot, but can’t describe political positions. If Mom always voted Republican, they can’t assume she’d do that again this year. She has to make the choice. If Dad only knows the presidential candidates, he doesn’t have to vote for state rep. If straight party voting is an option, he can pick that. The voter doesn’t have to be able to read. Rules on whether the voter must be able to sign the ballot vary by state, Sabatino said.

Richard Bartholomew, a retired architect and city planner in Chestnut Hill, helped his wife vote for the last time in 2014. Diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2007 at age 61, she could no longer read by then. He voted secretly by himself after that. He knew how much voting meant to her but also that she was no longer capable. “In cases where people have dementia, there will come a point where they really aren’t capable of understanding or reading or signing their ballot,” he said.

Karen Love, executive director of the Dementia Action Alliance, which represents people with dementia and their caregivers, said many with dementia are finding the “harshness” of this year’s election season so “emotionally disruptive” that they’ve disengaged from voting. The issue has not come up in support group meetings. The overwhelming concern at the moment is isolation caused by the pandemic.

Paulan Gordon, a member of the group’s board of directors, plans to continue her lifelong tradition of voting. Now 66, the Phoenix woman was diagnosed with vascular dementia in 2012. She has short-term memory problems and can no longer drive or cook but said she keeps up with the news and thinks voting is important for people like her because they need help with transportation, health care, and long-term care.

“I don’t need any help voting at all,” she said. She recognizes that may change in the future. Her husband will check her work after she fills out her mail-in ballot. “He helps make sure everything is in order,” she said.