When Kobe was held scoreless for the summer, and other stories I learned from ‘The Rise’ | Mike Jensen

Tell me things I don’t know. That’s a basic bar to get over in journalism, any form. That's what The Rise aimed to do. The achievement: Masterful.

A favorite passage in The Rise – Kobe Bryant and the Pursuit of Immortality. Kobe was living in Italy where his dad was playing professional basketball, after Philly hoops impresario Sonny Hill had told Joe Bryant to think about trying Europe with his NBA days over.

There’s a great scene, Kobe’s mother out for a morning jog, how a male motorist would roll down a window and catcall at her, how she would casually turn her head and shout a simple expletive, universally understood.

Kobe was around his father’s games, would grab a mop to wipe the court during games. Once, Kobe made a deal with the team owner. He’d wear a sweatshirt advertising the owner’s business … But you have to buy me a red bicycle.

All there, so early, adapting the father’s artistry, the mother’s intensity, the emerging Mamba mentality, demanding a coach get teammates to pass him the ball, understanding that was, in fact, the way to win. Then the family moved back to Philadelphia, and in the summer of 1992, Bryant played up a level in the Sonny Hill League.

Scoreless, for the summer.

“Not a meaningless breakaway layup in a blowout, not a wing-and-a-prayer jumper, nothing. He had shamed his father and his uncle, and he briefly considered no longer playing basketball and focusing on soccer … But instead he rededicated himself to basketball …”

» READ MORE: The sides of a teenage Kobe Bryant that few got to see | Mike Sielski

Tell me things I don’t know. That’s a basic bar to get over in journalism, any form. You need to add perspective, and great sentences – you want the conversation to be elevated to the skies. Just start by telling me things I don’t know.

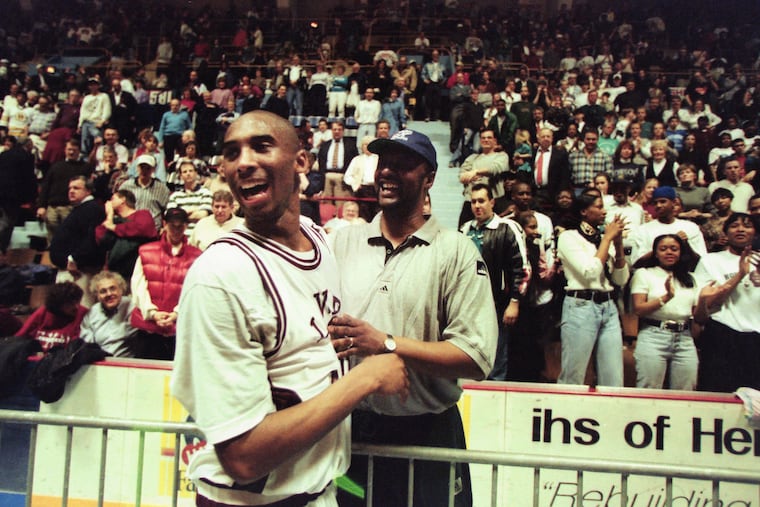

A high bar to get over when you’re writing in this city about Kobe Bryant’s early years. Stories have been told. I never covered Kobe, but I was in a corner of the Palestra when Lower Merion faced Coatesville in the playoffs, and made a field trip to a Central League game with some friends. Go See Kobe was the only agenda item.

So when Inquirer columnist Mike Sielski took on the task of writing this book that is now out, there was no question, the bar was high.

The achievement: Masterful.

I’d say that if Sielski weren’t my good friend of several decades. I’d write that about an author I’d never heard of, if this was the output, which is why it is required to write about a colleague. Such an important piece of local history, of Kobe’s history.

Here was Kobe at Bala Cynwyd Middle School, a coach determined to make it all about the team, the entire team. “This, Kobe could not abide. He shot quickly once. [George] Smith benched him. He shot quickly again. Smith benched him again. He pouted and grimaced each time he left the court, putting on such a petulant display that his father, to calm him down, whispered something in his ear in Italian.”

So Kobe was a bad teammate? No, no, no. His future high school coach handled it all skillfully, bringing the eighth-grader up to practice with the high school team. The book gets to the heart of how Kobe later led Lower Merion to a state title, how he found a teammate willing to get in the gym before school, the teammate rebounding, Kobe shooting. At the school, “one of the defining paradoxes of Kobe’s entire life. He could relate, and he could not relate.” The examples are all there, from classmates and teachers.

The recruiting tales are all there, from La Salle hoping against all hope that Joe Bryant working as an assistant would lead the son to 20th and Olney. It was never going to happen. The book explains why.

A Villanova assistant coach, Paul Hewitt, allowed himself the dream of bringing Kobe in with the same class that included uber-talented Tim Thomas and others. Kobe did not dismiss the idea. Hewitt brought Jonathan Haynes, then Villanova’s starting point guard, to watch Kobe practice. Kobe was transcendent. This is going to happen, Hewitt told himself.

“What’s so funny?” Hewitt asked Haynes, laughing at him afterward.

“Coach, you have no shot at getting this guy.”

“What do you mean?”

“Coach, this dude ain’t going to college. He’s going straight to the NBA.”

Insight at first sight. It’s all here. The great duels with Donnie Carr, battles won and lost with Chester High, how the Clippers once brought all-state graduate Zain Shaw back from West Virginia University to mimic Kobe in practice.

Deep interviews with Lower Merion coach Gregg Downer and with Jeremy Treatman, a former Inquirer sports stringer brought on the Aces staff to handle all the hoopla of Bryant’s senior year. Treatman later interviewed Kobe extensively. Those interviews are in this book.

Maybe this all gives away too much, or maybe not enough. Sielski captures it all, including a time Kobe went to his father’s practice in Italy, grabbed a basketball and began dribbling as the coach talked to the team.

“Kobe, stay seated.”

How did the child respond? With the same expletive his mother used for a cat-calling motorist. It’s all here, and immediately put into context, Sielski always scanning for the required higher ground, finding it.