Rowan professor offers Black Lives Matter course to discuss institutional racism. Teaching it is a mission, she says.

Alicia Monroe wants her students to become activists and “pay it forward.”

Professor Alicia Monroe wants students in her Black Lives Matter class to leave at the end of the semester with more than just three credits.

Monroe began teaching the Rowan University course several years ago, before the movement had become a rallying cry for racial justice in the wake of the killing of George Floyd in Minnesota. Since then, the class has taken on new meaning amid a national debate about policing and a call by some protesters to defund the police.

It is the first course of its type at Rowan, where about 33% of the nearly 16,000 undergraduates are students of color. Around the country, colleges and K-12 schools have been having frank conversations with students about the BLM movement and social justice. Some, like Stockton University, are making race courses mandatory.

» READ MORE: Stockton University is requiring incoming students to take courses on race. Will other colleges follow?

“This is not just a class that Black students should take, but a class that everyone should take,” said Jamar Green, 22, of Linden, a senior law justice and African studies major. “The movement doesn’t just affect the Black community; it affects everyone in America.”

In this year’s 18-member class, only two students are white — an older couple from Glassboro. The remainder are Black, Hispanic, and mixed-race undergraduates. The three-credit course is an elective offered only during the fall semester as a topics course in the African studies program.

The Glassboro couple — Marianne Schottenfeld, 77, a retired psychotherapist, and her husband, Matthew, 78, a retired educator — said the class has been an eye-opener. Married for 53 years, the pair are auditing the class.

”I have concerns about Black lives in general,” Marianne Schottenfeld said. “We thought this would be a good opportunity to mix and mingle with a diverse community.”

Said her husband, with a smile: “Sometimes I think that there is a little bit of restraint because we’re two old white people in the room. I’ve learned a tremendous amount.”

» READ MORE: Black Lives Matter Movement goes to school to teach students about social justice

Monroe, an adjunct professor since 2014, designed the course in 2016 to talk with students about institutional racism, bias, and prejudice. There are lessons on Black history, too, and current events like the international protests that erupted after Floyd’s death. She has changed the syllabus every semester to stay relevant.

”I want students to be informed,” Monroe said. “I want them to know how to pick and choose their battles, but they have to know their history in order to do that.”

Monroe begins her once-a-week class with a well-being check. She encourages students to share something that recently happened in their lives. Students relish the chance to talk about whatever is on their minds.

The professor went first, congratulating Argenis Sanchez, 23, on becoming a naturalized citizen. A Spanish major, the Dominican-born Sanchez came to the United States when he was 10.

An aspiring translator, Sanchez, a senior from Willingboro, said he never experienced racism in his homeland. The class has provided a perspective different from what is often portrayed in the news, he said.

”I wanted to know more about the movement,” said Sanchez. “If everyone at Rowan takes this class, it will open up their minds more.”

When it was Aimee Currie’s turn, she shared a story about a tense encounter with a group of white girls at a predominantly white college in the South she was visiting with her white boyfriend. The radio, television, and film major of mixed heritage was in a bathroom when the girls gave what she saw as a hostile stare. With her heart racing, she spoke out:

”Do you have something you want to say to me?” Currie recalled she asked. A verbal clash ensued, she said.

Monroe responded candidly to Currie: “Let’s unpack what happened.” She encourages the students to reject bullying or harassment, but neither was likely the case in this incident, she said.

“You were the instigator,” Monroe told her. “This was a stand-down moment.”

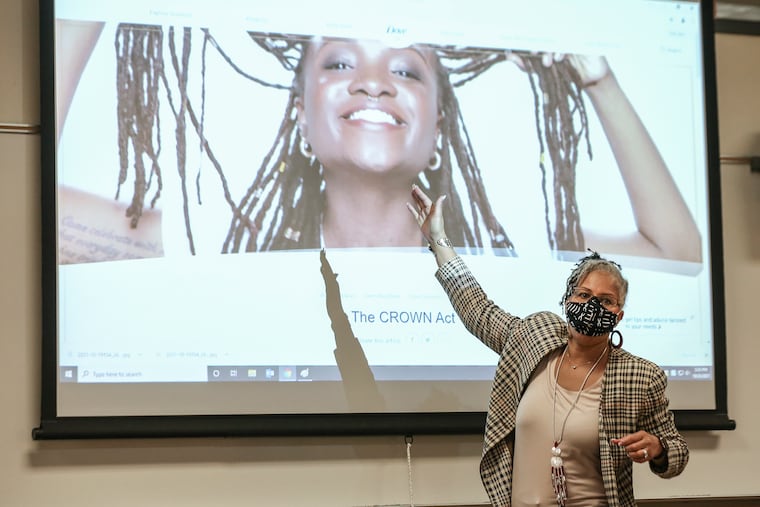

The class engaged in a lively discussion for about 90 minutes on topics including elections and voter registration, bias, and stereotypes in advertising for Black hair products. The following week, two attorneys delivered a “hands up, don’t shoot” presentation to teach students about their legal rights during a police stop and best practices, such as keeping their driving credentials handy.

This week, guest speaker Lloyd D. Henderson, an attorney and president of the Camden County East Chapter of the NAACP, talked about how policing influenced the movement, and explained BLM’s platform on defunding the police.

He also asked the students their reasons for taking the class. Monroe said she wanted the class to facilitate discussion about issues of race.

”Being a Black man in America, I had to take this course,” said Green.

Henderson urged the students to become activists and join a civil rights group.

“Take the class because you want to make a difference,” said Henderson. “This class should motivate you to do something. Otherwise, you’re just wasting time.”

Monroe agreed: “I want their lives to be changed. I want them to pay it forward.”

Monroe, who is also the assistant director of the Office of Career Advancement at Rowan, said she hopes the course will be offered more often. The class was shelved after one semester but brought back in 2019 because of student demands.

However, not everyone has embraced the course, and Monroe said she moved the class to a more remote location on campus two years ago after a professor teaching in the adjacent classroom was speaking so loudly that Monroe had to practically shout.

She felt hostility from other faculty and students as well, including one white man who confronted her outside her classroom and asked in an aggressive manner, “What is this you’re teaching?”

”I had to check him,” Monroe said.

The mother of four sons, Monroe said she believes teaching the course is a mission.

”It’s a very tumultuous time in this country,” she said. “I am just praying that God takes the wheel.”

.