How America’s first medical city birthed a racist maternal care system

A Philadelphia story about reproductive rights, American history, and medical racism.

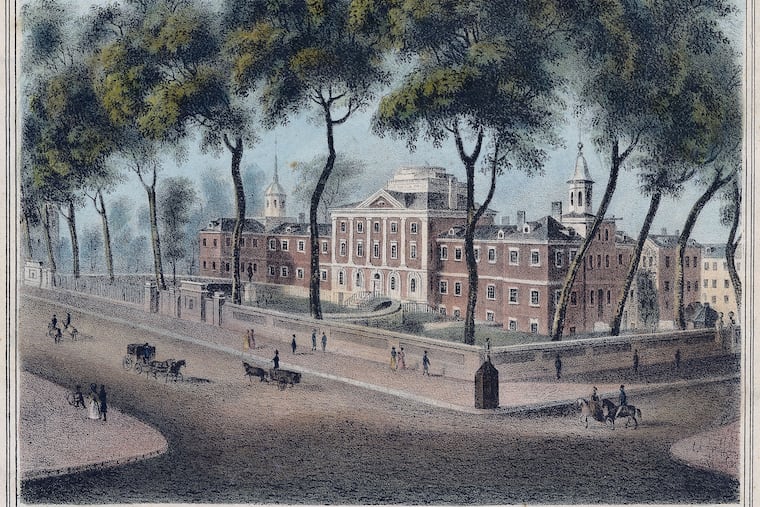

America’s first maternity wards were in Philadelphia — a lesser known fact about the city that birthed American democracy, and the nation’s first hospital and medical school.

From the earliest days of American maternal medicine, it was Black people who were exploited and whose bodies were used for medical advancement without their knowledge or consent.

In the latest installment of A More Perfect Union, we tell the story of these injustices and how they continue to shape America’s $111 billion childbirth industry. An industry that has made America the most dangerous developed nation in the world to give birth.

“When the water breaks,” focused on America’s maternal medicine crisis and its roots in Philadelphia, reveals the troubling origins of our nation’s maternal care institutions at a time when women’s reproductive rights are front and center.

Here are three takeaways from the story — part of a yearlong project from The Inquirer examining the roots of systemic racism in America and their continuing impact through institutions founded in Philadelphia.

Josephine Scott and her missing remains

The story opens with the harrowing history of Josephine Scott, a 25-year-old Black woman who died of birthing complications in Philadelphia in 1874, four weeks after a forceful and gruesome surgical delivery of a baby boy who did not survive.

The surgery was performed by William H. Parish, who later recounted details of the birth to the Philadelphia Obstetrical Society where he noted Scott’s race, the conditions of her home, and his judgment of her intelligence. He also gifted the society her pelvic bones to study and display. Scott was known to Philadelphia doctors who used her case to advocate for cesareans as a lifesaving intervention, though doctors chose to not perform the surgery on her.

The whereabouts of her pelvic bones are a mystery, despite Scott’s contributions to maternal medicine. The Society donated the collection that included Scott’s pelvic bone to the Mütter Museum Committee of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in the late 19th century. The museum said it had “no evidence that the pelvis in question was ever placed in our custody” in a recent statement.

The father of obstetrics’ body-snatching history

William Shippen Jr., who cofounded the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school, is also effectively the father of modern American obstetrics. At the nation’s first medical school, he lectured on anatomy, midwifery, and surgery. But the human cadavers he used to teach were obtained in ways that violate contemporary and historic medical ethics.

Shippen taught dissection by robbing an African burial ground called “Congo Square,” located in present-day Washington Square.

Armed Black Philadelphians began guarding the cemetery and, in one instance, engaged his team and repatriated a stolen corpse. While an attending physician at the Almshouse, a hospital for the indigent, Shippen also stole the bodies of dead patients.

As “the seat of racial science in the United States,” said historian Christopher D.E. Willoughby, Philadelphia institutions including Penn provided the pseudoscientific arguments that baked in enduring ideologies that Black women were somehow different.

Penn leaders have yet to fully reckon with the dark side of some of the institution’s brightest stars. Perelman currently has an endowed professorship of obstetrics and gynecology in honor of Shippen. In literature on the school’s website, there’s no mention of his body-snatching legacy, despite research from the Bethel Burying Ground project and the Penn and Slavery Project emphasizing this.

Racial disparities that persist

Labor and delivery doctors in Philadelphia laid the groundwork for the institutionalized maternal care system in a country that is last among developed nations for maternal mortality.

Disparities between Black and white patients that continue today began early — as early as the 18th century when Pennsylvania Hospital began operating and when hospital managers charged Black patients more than white patients, for example.

Today, the injustices are revealed through firsthand stories of patients who are denied equal care, and can be seen within medical statistics. Black people are nearly three times more likely than white people to die of maternal morbidity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In addition, modern American doctors are significantly more likely to give cesarean sections to Black birthing people than to white ones, studies show. With an estimated 15% to 64% increased likelihood for surgical delivery, Black parents face elevated risk for surgery-related complications like infection, blood clots, and hemorrhage.

Hospital data show that Black people began to experience disproportionate harm from C-sections in the 1990s.

“We know that Black women are three to four times more likely to die due to pregnancy-related causes than white, Asian, or Latinx women,” said Florencia Greer Polite, Penn Medicine’s chief of general obstetrics and gynecology. “[C]learly race plays a part in pregnancy and birthing. And when we say race, we really mean the results of systemic racism.”