N.J. judge may decide whether state must fix school segregation

Gov. Phil Murphy’s administration, meanwhile, said plaintiffs were demanding an unprecedented ruling without taking into consideration the root causes of racial imbalances in the state’s schools.

New Jersey’s public schools are deeply segregated, with stark differences in racial composition between communities, and the state is to blame, a group of civil rights advocates, children, and parents suing the state argued before a Mercer County Superior Court judge Thursday.

Gov. Phil Murphy’s administration, meanwhile, said plaintiffs were demanding an unprecedented ruling without taking into consideration the root causes of racial imbalances in the state’s schools.

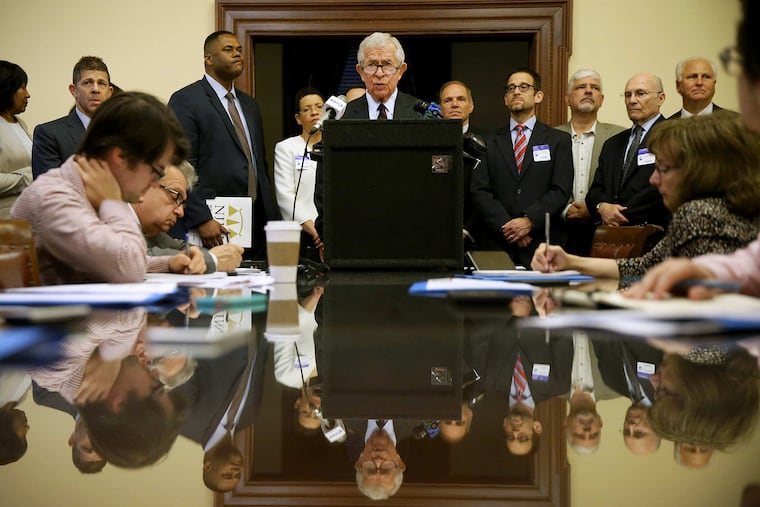

Judge Robert Lougy didn’t issue an immediate decision on plaintiffs’ request to find the state liable for school segregation, or the state’s request to dismiss the case. The oral arguments came nearly four years after the case was filed by the Latino Action Network and NAACP New Jersey State Conference, among others, accusing the state of creating and maintaining a segregated school system that violates the constitutional rights of children statewide.

They point to New Jersey’s constitution, which prohibits segregation because of race in public schools, and decisions by the state’s Supreme Court that say that provision applies not just to de jure segregation — required by laws — but de facto segregation that happens without a law ordering it.

The case “is about racial justice in a state that congratulates itself about being fair and just and egalitarian, but is in fact among the worst in the nation when it comes to segregation in public schools,” said Larry Lustberg, a lawyer for the plaintiffs, citing “indisputable benefits” of integrated schooling.

On average, between 2015 and 2020, more than a quarter of Black students in New Jersey attended schools that were more than 99% nonwhite, Lustberg said. Two-thirds of Black students attended schools that were more than 75% nonwhite. He cited similar figures for Latino students, with more than 15% attending schools that were more than 99% nonwhite, and 62% attending schools that were more than 75% nonwhite.

In 2016-17, 45% of New Jersey’s 1.4 million public school students were white, while 27% were Latino, 15.5% were Black, and 10% were Asian.

Looking beyond the statewide numbers, segregation persists between neighboring districts, Lustberg said, describing very different racial compositions of schools a few miles apart in Essex County. In written filings, plaintiffs cited Camden County as another example — with student populations that are more than 93% nonwhite in Camden, Lawnside Borough, and Woodlynne Borough, and more than 75% white in 12 districts, including Haddonfield, Haddon Township, and Audubon Borough.

Those contrasts “hint at the solution,” Lustberg said: “Don’t consign students to going to school in the district in which they live. Give people a choice.”

He asked Lougy to find the state liable for segregation to start a process of determining how to address the issue.

Deputy Attorney General Christopher Weber — who argued in a written filing that a remedy would require “essentially obliterating the State’s entire public school system” — told Lougy on Thursday that statistics alone didn’t prove the state was at fault. Plaintiffs hadn’t pointed to any case in which a court had issued such a ruling, he said.

“There is no such precedent, and there certainly isn’t any in this state,” Weber said. He also said plaintiffs hadn’t articulated a clear definition of what constitutes segregation — a determination that he said “demands an understanding of a variety of factors,” including access to affordable housing and transportation, shifting demographics, and parental decisions to enroll children in private schools.

Lustberg said the scope of New Jersey’s racial gaps couldn’t be ignored.

“The question here is whether there’s racial balance, and under any standard you would come up with, there’s none here,” he said.

Invoking the groundbreaking 1954 desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education, Lustberg said the state’s contention that students were already receiving the “thorough and efficient” education guaranteed by its constitution “amounts to arguing that ‘separate but equal’ is somehow constitutionally unproblematic.”

In considering Thursday’s arguments, Lougy could rule in favor of plaintiffs, finding that the state had violated students’ rights, or side with the state and dismiss the case — with the decision potentially winding up before the state Supreme Court. He could also allow the case to proceed to trial.

While plaintiffs had been in settlement talks with the state after filing the case in 2018, those negotiations broke down. Former state Supreme Court Justice Gary Stein, who leads the New Jersey Coalition for Diverse and Inclusive Schools group that has organized plaintiffs in the case, said the state had since “dragged out the discovery process.”

“This can be politically difficult,” he said.