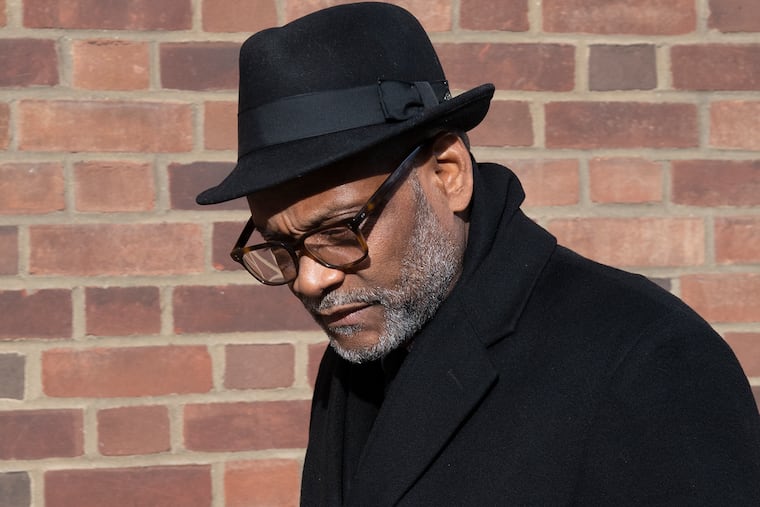

Former CEO at Philly music icon Kenny Gamble’s nonprofit convicted of embezzlement, bribery

The verdict comes less than two years after Rahim Islam, 66 and Shahied Dawan, 72, were acquitted in a separate trial of bribing Philadelphia City Councilmember Kenyatta Johnson.

A former executive at the community development nonprofit founded by Philadelphia music legend Kenny Gamble was convicted Wednesday of fleecing the organization out of more than a half-million dollars and then bribing an elected official in Milwaukee as part of a scheme to cover the cash crunch brought on by his theft.

A federal jury took roughly 10 hours to conclude that Rahim Islam, the former CEO of Universal Companies, looted the nonprofit by awarding himself five-figure bonuses without the approval of its board and embezzled hundreds of thousands of dollars more through reimbursements for personal expenses like $16,000 in gym membership fees and vacations with girlfriends to Orlando, Jamaica, and the Bahamas.

In all, prosecutors said, he, with assistance from Universal’s former CFO Shahied Dawan, drained roughly $571,000 from Universal’s coffers between 2011 and 2018 — all while the nonprofit struggled to come up with cash to support its core missions of providing affordable housing in blighted Philadelphia neighborhoods and educating children through the charter schools it operated across the city.

“You can’t be Big Willy on somebody else’s dime. You can’t live a high life with somebody else’s money,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Linwood C. Wright Jr. said during closing arguments Monday. “That money was meant to support schools; instead, it became a piggy bank, and [they] took full advantage of it.”

Islam, 66, now faces up to 20 years in prison on the most serious counts of conspiracy, wire fraud and honest services fraud for which he was convicted Wednesday.

The jury also convicted Dawan, 72, of one count of conspiring to cover up Islam’s thefts as well as $80,000 in unapproved bonuses he personally took home — a charge that could send him to prison for up to five years. But it acquitted the former accountant on 11 other charges, including all those connected to the political bribery scheme.

The verdict comes less than two years after both men were acquitted in a separate trial of bribing Philadelphia City Councilmember Kenyatta Johnson and his wife, Dawn Chavous.

In that case, their attorneys convinced jurors that the government had failed to establish that any corrupt bargain existed between the Universal executives and the council member, despite payments they made to Chavous as a consultant while seeking Johnson’s support for legislation to benefit their organization.

But as prosecutors returned to court for this latest trial earlier this month, they came armed with evidence that proved harder to defend against: direct testimony from the official they’d been accused of paying off.

Former Milwaukee School Board President Michael Bonds told jurors Islam paid him $18,000 in bribes between 2014 and 2016 disguised through invoices to a company he owned, African American Books & Gifts.

In exchange, Bonds advocated for several measures that benefited Universal’s charter school operations in Milwaukee, including supporting its bid to open a third campus in the city and to defer $1 million in lease payments it owed for another school operating out of a school district-owned property.

“I knew it was bribes. … I lied to [FBI] agents … It was difficult telling the truth,” said Bonds, who resigned his post, pleaded guilty to bribery charges in 2019 and is currently awaiting sentencing.

Throughout the three-week trial, prosecutors painted Universal’s entire bid to expand into Milwaukee as a boondoggle brought on by Islam and Dawan’s efforts to cover up the nonprofit’s dire financial situation — a state brought on, at least in part, by Islam’s liberal spending of the organization’s funds on himself.

Gamble founded Universal nearly 30 years ago after cementing his music legacy in the 1970s as the originator — along with songwriting partner Leon Huff — of soul music’s distinctive “Sound of Philadelphia” with such hits as Freddie Scott’s “(You) Got What I Need,” Billy Paul’s “Me and Mrs. Jones” and the O’Jays “For the Love of Money.”

» READ MORE: Who is Kenny Gamble? From Philly soul to Universal Companies, here’s what to know.

He hoped the nonprofit he led along with wife, Faatimah, could turn back decades of poverty and lack of investment in the South Philadelphia neighborhood where he grew up with its focus on expanding affordable housing and educational opportunities.

But by 2010, prosecutors said, Universal’s real estate development wing had all but ceased operations due to its inability to fund projects, and its charter campuses in Philadelphia were struggling to fulfill their mission of educating children.

“The reality is we need to cut out all [non]essential expenditures for 6 months and reduce all [non] essential staff for the same period of time,” Dawan wrote in an email to Islam in 2013. “We are out of cash!”

In government court filings, former employees at Universal schools said the nonprofit resorted to hiring under- and unqualified staffers because they could not afford to pay properly trained professionals.

Money was so tight on one campus, that one former Universal teacher told investigators she resorted to having her students cook and sell lunches to faculty members to raise funds to pay for basic classroom supplies like paper, textbooks, and pencils.

Meanwhile, its top executive was draining Universal’s coffers.

Islam awarded himself at least $280,000 in bonuses and raises between 2011 and 2016 and Dawan paid himself $80,000 — salary bumps that Universal board members testified they never voted to approve.

At the same time, Islam submitted more than $211,000 in reimbursement requests to the company for personal expenses including car insurance, dinners, gym memberships, tickets to Broadway shows, family vacations and romantic getaways for him and his girlfriends. He even charged Universal for a trip one of his paramours took to Seattle to attend a live taping of the Oprah Winfrey Show.

“They were laying people off — people were losing their jobs — at the same time Mr. Islam was doing whatever he wanted to do with the company money,” said Wright, who prosecuted the case along with colleague Mark B. Dubnoff. “And Mr. Dawan was signing off on it.”

David M. Laigaie, an attorney for Islam, chalked up any personal spending that had made its way onto the former CEO’s reimbursement forms as an accounting error.

“While there were mistakes,” he told the jurors in his opening statement earlier this month, “there was no concentrated effort to cheat.”

As for the bonuses, defense attorneys said, both men more than earned that extra pay by managing an organization with budgets in the hundreds of millions of dollars, funded by government grants and donor contributions.

Dawan’s lawyer, Thomas O. Fitzpatrick, stressed that his client hadn’t been accused of any personal spending on himself and had merely signed off on his bosses’ expense reports. He’d had no direct dealings with Bonds, aside from approving the invoices Islam arranged for the school board president to submit.

And when cash ran short, Dawan risked his own money to bail it out, the attorney said.

“Universal was his life’s work,” Fitzpatrick told jurors. “And when the company was in trouble, he took [equity] out of his home and put it into Universal.”

But if Islam and Dawan had hoped that Universal’s Milwaukee expansion would buoy the organizations ailing finances, those expectations were eventually dashed.

The three schools it operated there continuously struggled to meet enrollment targets and in the middle of the 2016-2017 school year, Universal closed the campuses, terminated its contract with the school district and never repaid the $1 million in rent payments Bonds helped them defer.

The nonprofit continues to operate charter schools in Philadelphia, though its portfolio has shrunk to five campuses.

A spokesperson for Universal hailed Wednesday’s verdict, saying the organization was eager to put the matter behind it and “devote its time and resources exclusively to its dedicated missions.”

“The jury has proved the breach of trust,” he said in a statement. “And we will seek full restitution for the losses incurred.”

In addition to the bribery and embezzlement counts, jurors convicted Islam on charges of tax fraud, concluding he failed to report more than $550,000 in income between 2011 and 2016 — most of it money he’d been accused of stealing from Universal.

U.S. District Judge Gerald A. McHugh is expected to set a sentencing date for both men later this year.