Most warnings are false alarms, but tornado watches get attention — with good reason

Tornado "warnings" well outnumber actual tornado sightings in the Philadelphia region. Blame the limits of science, and expect more "false alarms."

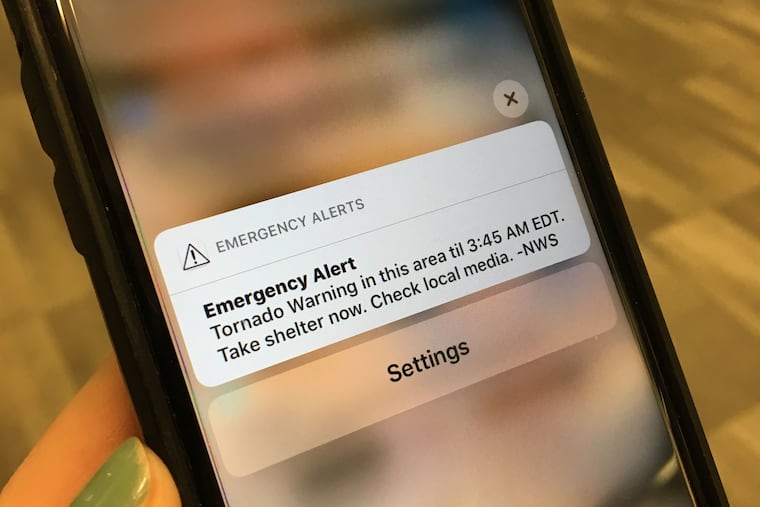

Nothing gets the public’s attention like the "T" word — even though statistics show that nearly three-quarters of all tornado warnings are “false alarms.”

Consider that tornado warning issued by the National Weather Service’s Mount Holly office at 3:19 a.m. on Monday, April 15. It covered an area inhabited by 2.7 million people, from Claymont, Del., to all of Philadelphia to Glenside to Palmyra.

Thanks (depending on your viewpoint) to the nation’s sophisticated public-alert technology, thousands were roused from their beds and advised to take shelter, although some were oblivious or disdainful, or just chose to roll the bones.

It rained, the winds roared, but in the end no tornadoes were sighted anywhere near Philadelphia, although one did touch down in deep Delaware.

Wouldn’t it be better to wait until a tornado forms before setting off the alarm bells? Why risk scaring the daylights out of people?

A tornado has a spectacular but very brief career.

Relative to other cyclones, tornadoes are pinpricks. A winter storm can affect thousands of square miles; a tornado, often only a few.

A winter storm’s fury can last several days. A tornado? “The average of life span is a couple minutes,” says Joe Miketta, who is the Mount Holly office’s warnings coordinator. “If we wait for a tornado being sighted, it’s too late.”

What triggers a warning?

Twisters are spun by tremendously complicated processes interacting at different levels of the atmosphere. Those alignments are difficult to predict.

The Storm Prediction Center, a national mayhem center in Norman, Okla., issues generalized tornado watches when it appears that the atmosphere is poised to riot over a given area.

This time of year, when the atmosphere is particularly frisky, the forecast floor at the center can resemble that of the National Hurricane Center’s on five cups of espresso, with warning bells going off every few minutes.

It is up to the local offices to issue warnings, and they rely on Doppler radar images — “tornado vortex signatures” several miles up in the atmosphere — that indicate a tornado is possible.

That’s a tremendous advance over old technology, but not all those signatures will be followed by tornadoes, and sometimes if they do form, they head in unpredictable directions.

So are warnings all sound and fury, signifying nothing but fright?

The April 14-15 period was an incredibly active one for tornadoes in the mid-Atlantic.

In all, eight were confirmed in Pennsylvania, where, on average, only eight touch down in a year, according to the weather service.

Delaware exceeded its quota for the year. On average it sees only one annually; two touched down early on April 15.

The first one tore a 6.2-mile-long path, 50 yards wide, through Laurel, in southwestern Sussex County, at 3:38 a.m.

Incidentally, at 3:31, the National Weather Service did issue a tornado warning for a far smaller area that included Laurel.

The tornado was stronger than most that land in the Tri-State area, according to Sarah Johnson, a meteorologist with the weather service in Mount Holly, an EF2 on the Enhanced Fujita scale, with winds estimated at 120 mph. One person was injured.

A weaker tornado touched down nearby in Milton about 20 minutes later.

How do we know when a tornado really does happen?

The weather service conducted investigations and determined the wind damage was circular, as opposed to “straight line” winds.

Asked why the agency bothers to verify whether winds were linear or circular, Gary Szatkowski, the former head of the Mount Holly office, responded that’s because we media people keep asking.

The findings do have at least one practical application, in that they help the service keep track of “false-alarm rates,” the object being to get better at this.

Yes, false alarms are quite high for tornadoes, says Miketta.

And, yes, they are likely to stay that way for a while.