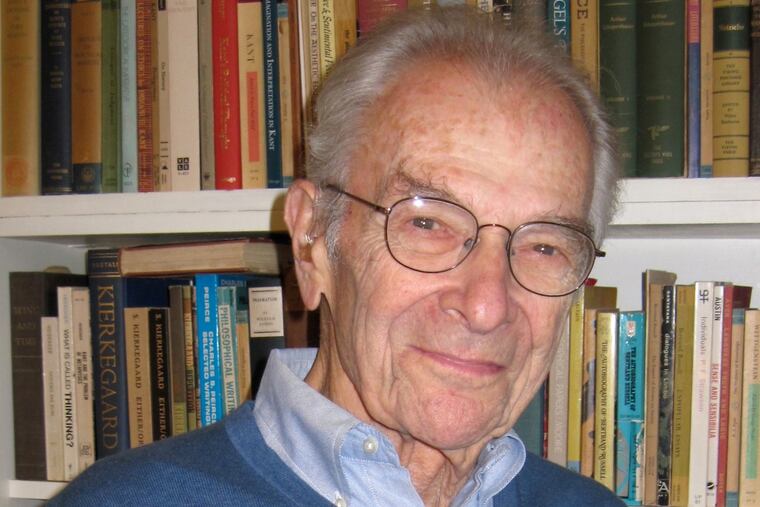

Harold J. Bershady, sociology professor emeritus, author, and editor, has died at 93

Former students said he had "the ability to take complex sociological ideas and relate them to issues important to students." They said he encouraged them "to think about the world in new ways."

Harold J. Bershady, 93, of Philadelphia, sociology professor emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania, author, and editor, died Saturday, Feb. 18, of kidney failure and congestive heart failure at Keystone House Hospice in Wyndmoor.

Professor Bershady won Penn’s Lindback Award for distinguished teaching in 1993 and told the Chestnut Hill Local newspaper in 2014 that he had likely instructed at least 10,000 students. He taught at Penn from 1962 to 2005 and told the newspaper that his parents encouraged his love of education and that “teaching is an obligation.”

“I could have kept teaching until I dropped, but it was time to step back,” he told the Chestnut Hill Local. “I had a great career teaching. I had wonderful colleagues. It was the joy of my life.”

His wife, Suzanne, said Professor Bershady particularly appreciated his interaction with students and other professors, and that his intellect and sense of humor made him an ideal instructor. Students praised his “warmth and compassion” in a 1992 nomination letter for the Lindback Award, calling him “one of the most significant sources of intellectual support in the department.”

They said he “makes learning sociology an exciting and provocative experience” and “challenges students to go beyond the limits of established theoretical paradigms, thereby empowering students to take the final steps toward becoming professional sociologists.”

Professor Bershady was the author and editor of several books on social science. The son of Jewish parents who emigrated from Ukraine, he wrote about religion and political philosophy, morality, intellectual standards, and how ideology influences social thought.

He published Ideology and Social Knowledge in 1973 and When Marx Mattered: An Intellectual Odyssey in 2014. One reviewer said Ideology and Social Knowledge is “analytical brilliance.” Another reviewer said When Marx Mattered is “erudite, poignant, and historically insightful.”

He also contributed to When Men Revolt and Why in 1971, and After Parsons: A Theory of Social Action for the Twenty-First Century in 2005. He edited Social Class and Democratic Leadership and Max Scheler’s On Feeling, Knowing and Valuing.

“He was always intellectually curious,” said his son, Matthew. “He engaged well with young people and helped me become a thinker.”

Professor Bershady supported the American Sociological Association and reviewed articles and books for the American Journal of Sociology. In 1999, he explained in an Inquirer article that modern attitudes were affecting how people treat one another.

“Public etiquette is a way of expressing involvement with others, of respecting others,” he said. “But that is changing, especially in this country. The change is due to a heightened degree of individuality, which eventually leads to the diminishment of certain forms of etiquette.”

Born April 17, 1929, in Toronto, Harold Joshua Bershady moved with his parents to Buffalo, N.Y., when he was 6. His family had left Ukraine, and he grew up speaking both English and Yiddish until he was 8.

As a boy, he enjoyed stories of the old country his grandmother would share and bedtime Bible stories about Moses, Egypt, and the promised land as told by his father. He listened to radio shows with his family, was mesmerized on visits to museums, and read comic books about superheroes.

“I am quite sure Moses and Superman fused in my boy’s mind,” he said in the first chapter of When Marx Mattered.

Later, he read more sophisticated books and noted how his family’s antisemitic experiences in Ukraine resembled the struggles of Native Americans who had lived near Buffalo. “The analogy I drew between the hurt the Indians suffered from the Europeans and the hurt my family suffered from the bandits in Ukraine doubtless became one of the springs that fed my later radicalism,” he said in When Marx Mattered.

He earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in sociology and philosophy at the University of Buffalo, and a doctorate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1966. He married Suzanne Kottek in 1958, and they had son Matthew, and lived in West Mount Airy and Chestnut Hill.

Professor Bershady enjoyed classical music, wrote unpublished mysteries over the last few years, and was proud of his innate determination to see things through. “Time has constantly altered my appearance, but my stubborn essence has remained,” he said in When Marx Mattered.

He worked on an assembly line and as a welfare caseworker as a young man. He called himself a Social Democrat and told the Chestnut Hill Local: “Government has a role to play. … I don’t care how rich people are. I just don’t want people to be poor.”

“He was funny and humorous,” his wife said, “and he loved to share his passions. … It was magic.”

In addition to his wife and son, Professor Bershady is survived by a grandson and other relatives. A sister died earlier.

A celebration of his life is to be held later.