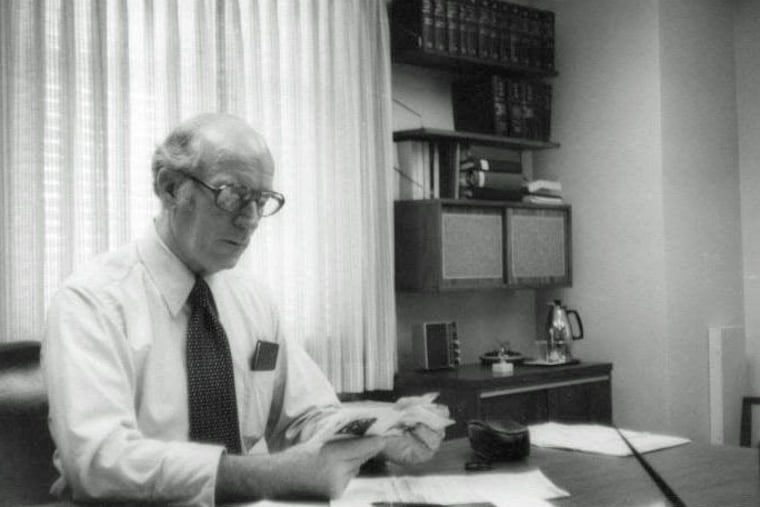

Joseph O’Dea, former Inquirer executive and family man, dies at 101

Mr. O’Dea was many things to many people, and he remained vibrant and lucid even as he crossed the century mark.

- Joseph O’Dea

- 101 years old

- Lived in Rydal

- His sons said he made them an Inquirer family

Joseph F. O’Dea, 101, of Rydal, a Navy veteran and former vice president of labor relations at The Inquirer, died Tuesday, Dec. 8, of COVID-19 at his home.

Mr. O’Dea was many things to many people, and he remained vibrant, lucid and involved with his family even as he crossed the century mark.

He was a fix-it man around the house, and daughter-in-law Ethel O’Dea still cherishes the wall clock he built for her. He was a tech wizard, and his wife, Carolyn, used to joke that he spent more time with his girlfriend — his desktop computer — than with her.

He was vice president of labor relations at The Inquirer during the tumultuous 1970s, when a series of strikes pitted management against union employees in contract negotiations. But the unflappable Mr. O’Dea never let the talks get personal or hateful, and union representatives said they respected his preparation and decency.

Most of all, Mr. O’Dea was an up-close study of character, support, and love for his sons, Lee and Joe.

“It was an honor to be his son,” Joe O’Dea said. “He was the finest man I’ve ever known.”

“He had integrity,” Lee O’Dea said. “He was incorruptible.”

Mr. O’Dea grew up on 25th Street in North Philadelphia, and Magee Avenue in the Northeast. He graduated from Roman Catholic High School and Temple University, and worked in management at The Inquirer from the early 1950s until his retirement in 1986.

He was a newspaperman his whole life. Born in 1919, he sold and delivered The Inquirer as a kid. After high school for a bit and again after a three-year stint in the Navy during World War II, Mr. O’Dea drove an Inquirer delivery truck. When he started, horse-drawn wagons were still being used for the Center City route.

He also met Carolyn LaVallin at The Inquirer, and they married in 1959. She administered one of the tests he took to move up in management, and they went on to raise their sons in Rydal. Mr. O’Dea worked in the general accounting and circulation departments at The Inquirer before moving on to labor relations.

The new assignment fit him perfectly.

“His mix of smarts, empathy and sense of fairness earned the respect of his colleagues and a reputation as one of the region’s premier labor leaders,” Joe O’Dea wrote of his father.

William K. Marimow, former editor of The Inquirer, worked as a labor reporter for the paper from 1973-75 and covered Mr. O’Dea during several of the newspaper strikes. He was struck by Mr. O’Dea’s kindness to others, loyalty to the paper, and energy for his job.

“He was a man of bedrock integrity,” Marimow said. “He was an idealist of the highest ideals. He was steady, steadfast, analytical and with a shrewd perspective. And he was a better person. He had a sparkle in his eye.”

Both Lee and Joe O’Dea tell of watching their father maneuver the ups and downs of lengthy and often contentious labor negotiations. Through it all, they said, Mr. O’Dea insisted on fairness and respect for the aims of both sides. He had a calming influence on people, they said, and he always shook hands at the end.

Frank Dougherty, a former longtime union member and reporter at The Inquirer and Daily News, called Mr. O’Dea “a decent man, a prince of a man as well as a noble adversary” in a tribute.

One story has that Mr. O’Dea, when accused of being out of touch with the union folks, smiled and produced his old Teamsters card from when he drove an Inquirer truck.

At home, Mr. O’Dea was just as calm, and the boys remember him playing peacemaker between them. He liked to garden. He could fix practically anything and would never willingly call a repairman. He could navigate Facebook and email and the rest of the internet before many of his younger relatives.

A first-generation Irish American, he helped support his family during high school when things were tough in the 1930s. He visited Ireland later, and he and Carolyn, married for 58 years until her death at 97 in 2017, traveled and spent summers at their place in Avalon.

“He was,” Joe O’Dea said, “always true to himself.”

In addition to his sons and daughters-in-law, Mr. O’Dea is survived by six grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. A private service was held Dec. 15.