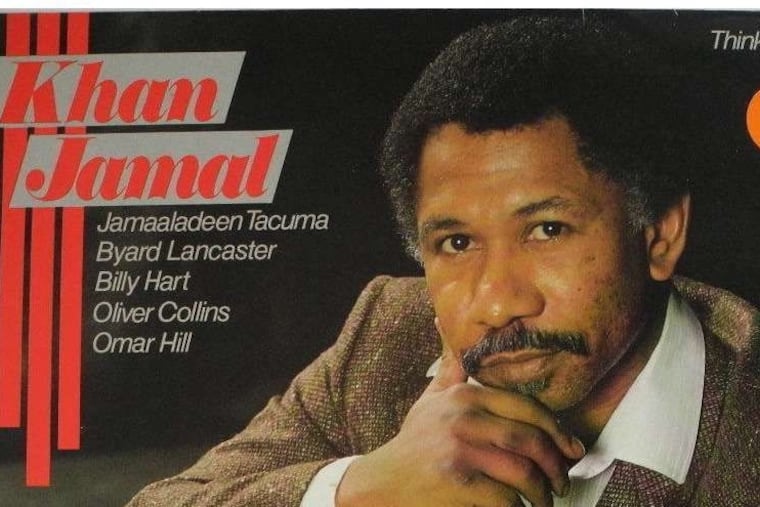

Khan Jamal, jazz vibraphonist known for avant-garde spiritual music, dies at 75

Khan Jamal, 75, known for his experimental jazz fusion and avant-garde compositions, died Monday, Jan. 10, at Chestnut Hill Hospital.

Khan Jamal, 75, a Philadelphia jazz vibraphonist, composer, and marimba player known for his spiritual, experimental, and avant-garde music, died Monday, Jan. 10, of kidney failure at Chestnut Hill Hospital.

Mr. Jamal, who played with Sun Ra Arkestra and helped found the Sounds of Liberation collective, “was one of the greatest minds this country has produced,” said Philadelphia tenor saxophonist Odean Pope. ”He was also very good friend of mine.”

Pope, 83, played in Mr. Jamal’s Change of the Century Orchestra that included drummer Philly Joe Jones, saxophonist Archie Shepp, and two members of one of Mr. Jamal’s earlier groups: guitarist Monnette Sudler and saxophonist Byard Lancaster.

“There will probably never be another vibe player that has his sound,” Pope said. “He had an original touch. His music is going to be current for a long time.”

Mostly inspired by the vibraphonist, pianist, and bandleader Lionel Hampton, Mr. Jamal played early in his career with the Sun Ra Arkestra, whose music is considered a pioneer in what later became known as Afrofuturism. He also played with Cosmic Forces and Sunny Murray.

In 1971, Sudler, Mr. Jamal, and percussionist Omar Hill were the founding members of the Sounds of Liberation collective, which featured young musicians responding to the political mood in the country.

“He loved creating experimental, avant-garde music. But at the same time,” Sudler said, “the melodies Khan created were also very beautiful and spiritual.”

Sudler was only 19 and Mr. Jamal was about 25 when the group began and they often played at Black liberation community festivals, Mills told The Inquirer in 2019. Its first album, New Horizon, also known as Sounds of Liberation, was released in 1972, and was reissued in 2010.

Dwight James, one of the members of Sound of Liberation, said he and Mr. Jamal grew up at a time when professional musicians lived all over North Philadelphia.

“You always heard music coming out of someone’s house, James said. “On my block, I mostly heard jazz.”

In a 2009 interview, Mr. Jamal talked to filmmaker and musician Jason Fifield about living near John Coltrane’s house at 1511 N. 33rd St., where musicians continued to play music long after the saxophonist had left Philadelphia for New York in 1958.

They were invited by Coltrane’s “Cousin Mary” Alexander to practice or have jam sessions in the back yard.

“Lots of musicians used to come there,” Mr. Jamal said in the film. “I used to sit on the steps and listen to them all the time. From that, music was in my blood. I was born a musician.”

Lovett Hines, artistic director for the Philadelphia Clef Club of Jazz and Performing Arts, said Mr. Jamal was invited by Alexander to become part of the John W. Coltrane Cultural Society, where musicians would give master classes and go out as jazz ambassadors into the community.

Born July 23, 1946, as Warren Robert Cheeseboro in Jacksonville, Fla., Mr. Jamal was the son of Henry McCloud, an entrepreneur, and Willa Mae Cheeseboro, a pianist. He was the oldest of four children.

He left Florida as a child and was raised in Philadelphia, said his brother, Johnnie P. McGee III. After his parents separated, he lived with his grandmother in a house on 28th Street, across the street from where his mother lived with her new husband and three younger children, McGee said.

After graduating from Edison High School in 1965, Mr. Jamal served in the U.S. Army in Vietnam. Upon returning to Philadelphia, he studied music at the Granoff School of Music, the Combs College of Music, and privately with educator Bill Lewis.

In 1970, Mr. Jamal and Janice Browning, his high school sweetheart, had their first son. They married in 1976, and had a second son. The marriage ended in divorce and his ex-wife died in 2014.

As recently as 2019, DownBeat magazine ranked Mr. Jamal among the top vibraphonists in the world.

“He got more appreciation in Europe than in the states.” said his son Khan Jamal II. “Because Europe was big on jazz. They loved him over in Copenhagen and London.”

In addition to his son and brother, Mr. Jamal is survived by a second son, Tahir Jamal, three grandchildren and many relatives and friends.

A memorial service is being planned by the Clef Club at a future date, his son said.