Coronavirus made me ‘old,’ but I still feel young | Perspective

My wife and I consider ourselves middle-aged, but we recently learned that's not how the world sees us.

The email arrived last week from my old friend, Graham McDonald, inviting six of us to consider participating in a National Science Foundation study of couples who have been having concerns about their memory. The purpose of the research, according to Graham’s daughter, who is working on the project, was to help couples manage “cybersecurity and aging with memory loss.”

To put this in context, Graham is an old friend — old in terms of both longevity (we both arrived as freshmen at Trinity College, where he was known as “Butch,” in September 1965) and old in terms of age. Like me, he is 72.

Until the coronavirus crisis swept over us, I had never considered myself “old.” I had always believed that there were 72-year-olds with the spirit and energy of a 25-year-old and that there were some 25-year-olds weighed down with the spiritual restraints of someone much older. After all, I reasoned, I worked out at least an hour a day on the treadmill until I was bathed in sweat, I could still pump out 30 push-ups, and my memory seemed intact, though some of what I recalled most vividly — the phone numbers of high school friends who had decades ago left our hometown — seemed the most irrelevant.

But in mid-March, the first weekend that my wife Diane and I realized the seriousness of the approaching pandemic, I began to understand that even if we considered ourselves middle-aged, that was not the way the medical profession, the Social Security Administration, and even my two children — Ann and Scott, ages 44 and 40 — viewed us.

» READ MORE: How older adults and caregivers can weather the coronavirus pandemic | Expert Opinion

That Saturday night, we had driven from Center City Philadelphia out to an old friend’s home in Devon for dinner with two other couples. We didn’t shake hands with anyone there, but there was no semblance that night of social distancing — just good conversation, camaraderie, and a scrumptious home-cooked dinner. When we talked with our children about our night out, they were both deeply distressed because in their opinion, their “old parents,” who were far more vulnerable than the younger generation, had put themselves at risk.

Many of our contemporaries had the same experience during that time period. Their children seemed exceedingly concerned about the possibility that they would contract the coronavirus, and that because we were old, we were risking our lives. Of course, as we’ve all learned in the six weeks that have elapsed since then, their concerns were well-founded.

» READ MORE: For those in senior housing, coronavirus provokes both bonding and fear

As I began writing this piece, I consulted the dictionary to learn precisely how “elderly” was defined. What it said was this: Elderly is “past middle age and approaching the rest of life.” That, of course, begged the question of how old is “middle age,” which was defined as between 40 and 60 years old. A later definition, provided by Google, gave the range from 45 to 65.

So for the duration of the pandemic — whether it’s months or years — I will accept the fact that chronologically, I may be old. But I don’t plan on participating in any studies of the elderly unless I am lucky enough to reach my mother’s age. And she is 97.

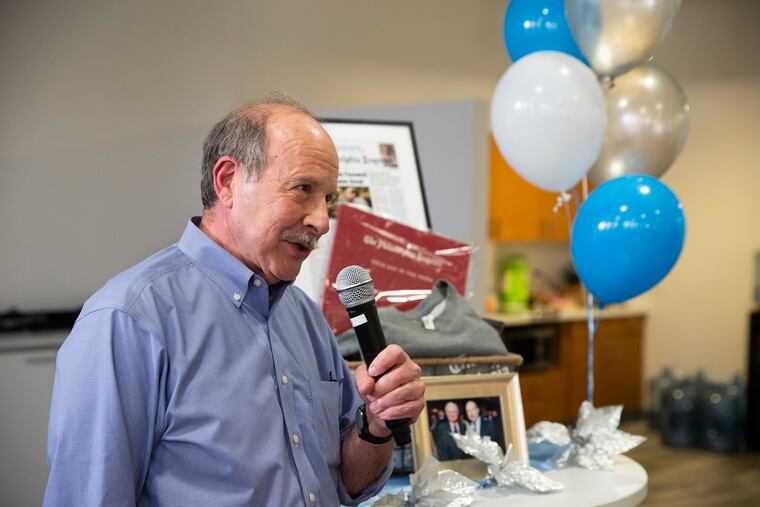

Bill Marimow, the former editor of The Inquirer, received two Pulitzer Prizes as an Inquirer reporter. He was also editor-in-chief of the Baltimore Sun and vice president of news at National Public Radio.