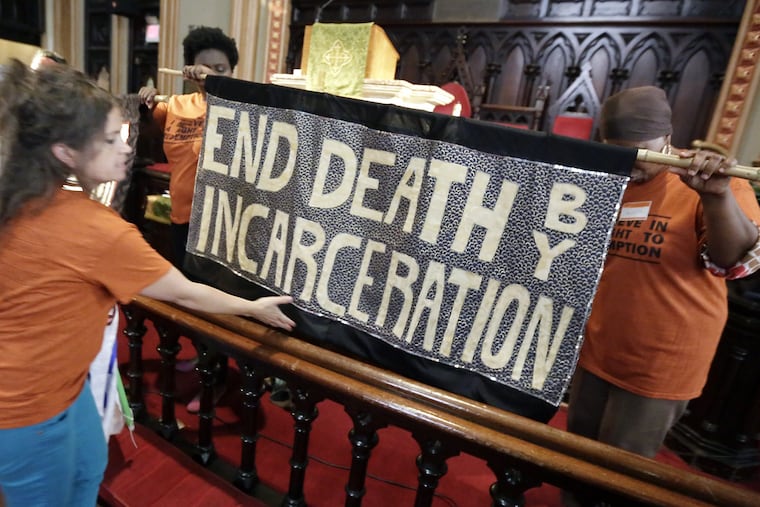

Death by incarceration must be abolished

At this moment in the United States, over 200,000 people are sentenced to die in prison.

Last month, a group of experts from the U.N. Human Rights Committee published a report condemning systemic racism in the United States criminal justice system. After an official visit to the U.S., where experts visited five detention centers and heard testimonies from 133 affected people, the authors of the report noted that a “racist criminal justice system erodes all efforts towards addressing systemic racism.” They offered 30 recommendations for reforms, including eliminating death by incarceration, also known as life sentences.

At this moment in the U.S., more than 200,000 people are sentenced to die in prison. Pennsylvania has the second-largest population in the country of prisoners serving life sentences without parole. No matter how much these individuals have transformed over the decades they’ve been behind bars, they will never see life beyond prison walls again.

The U.S. employs life sentences at an unparalleled rate. A global human rights analysis of 113 countries found the number of people serving life sentences in the U.S. is more than all of the rest of the countries combined. It is a cruel form of punishment that takes away the human capacity for redemption.

Furthermore, life sentences disproportionately impact people of color, our elders, and our children. According to the Sentencing Project, more than two-thirds of those sentenced to die in prison in the United States are people of color. While only 12.4% of the U.S. population is Black, 46% of all of those serving life sentences nationwide are Black. Half are over the age of 50. A life sentence disappears sources of wisdom from Black families and communities forever.

One of us — Songster — suffered under the weight of this inhumane treatment for 30 years. After running away from his home in Brooklyn with a childhood friend at age 15, he spent the next four months caught up in the drug trade in Philadelphia. In a fight one evening, he and that friend stabbed a fellow runaway to death. Because the mandatory minimum for first- and second-degree murder in Pennsylvania is life without parole, Songster was sentenced to die in prison.

At the time, the U.S. had over 3,000 people serving life sentences for crimes committed when they were children. The rest of the world had zero. The U.S. Supreme Court intervened in the cases of our condemned children via Miller v. Alabama, ruling in 2012 that mandatory life-without-parole sentences for minors are unconstitutional. This ruling offered people like Songster a ray of hope. It required that everyone serving mandatory life without parole for an offense they committed under the age of 18 be resentenced. As a result, Songster was immediately eligible for parole.

After spending 30 years behind prison walls, he now serves as program manager of Healing Futures, Philadelphia’s first youth-focused restorative justice diversion program, at the Youth Art and Self-empowerment Project. The city refers young people in cases involving assault, robbery, and other felonies to the program, and over several weeks in a restorative community conference, those youth are prepared to come face-to-face with the people they have harmed to make amends.

The process ends after the young person has completed an extensive plan to make things right. This could include volunteering at an organization of the harmed person’s choosing, therapy, mentorship, and community beautification.

One story of transformation is not an exception. A 2020 study out of Montclair State University found that among people who were sentenced in Philadelphia as juveniles to life without the possibility of parole and then subsequently released, the recidivism rate was only 1.14%.

Not only do formerly incarcerated people pose very little risk to public safety, they are also uniquely positioned to strengthen our communities. The New York Times recently profiled formerly incarcerated people who were sentenced to life as children, and many of them now serve as mentors in vulnerable communities, engaging in violence prevention and equipping young people with conflict resolution skills.

On Tuesday and Wednesday, we will be part of a coalition of formerly incarcerated people, family members, and advocates going before the United Nations in Geneva to testify that the U.S. is violating the International Bill of Human Rights prohibition of torture and racial discrimination by sentencing people to death by incarceration.

We will implore the United Nations to call for the abolition of all life sentences in the U.S. We will share testimonies of incarcerated friends and family members who are organizing healing circles inside prisons to help their peers atone for crimes they committed and repair the harm they have caused. And we will bear witness to the human capacity for redemption.

Kempis “Ghani” Songster is the program manager of Healing Futures, Philadelphia’s first restorative justice diversion program for youth. Nikki Grant is the policy director and cofounder of the Amistad Law Project.