Trump’s attempts to hide the unpleasant truths about our actual history are the real disparagement

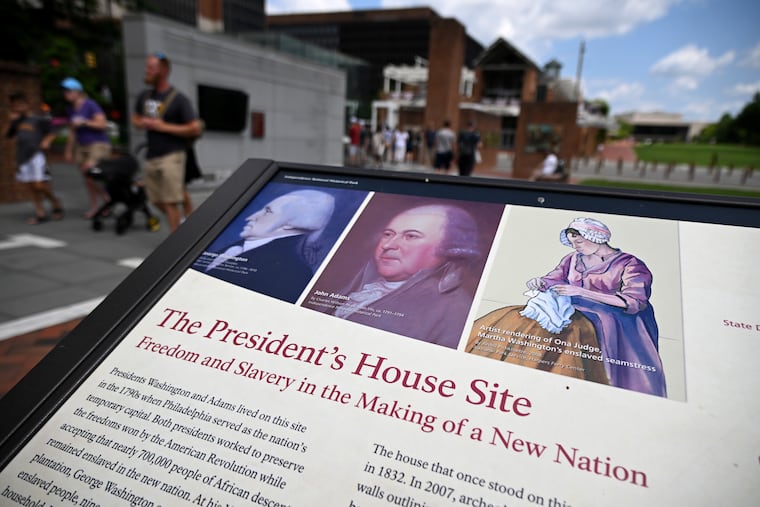

The President's House site is not all that it could have been, but it remains one of the most prominent monuments in the nation to openly acknowledge how much American liberty depended on slavery.

Why can’t this country tolerate telling the truth about slavery publicly for more than a few short years at a time?

That was one of the first thoughts that occurred to me when I learned the Trump administration wants to censor historical content across the National Park Service system that doesn’t promote “greatness” or “progress.”

On the chopping block at our own Independence National Historical Park are displays at the President’s House at Sixth and Market documenting the brutish enslavement of Africans by the nation’s founders.

The administration’s moves are yet another example of a historical pattern in which our nation holds these hard truths in the light for approximately a decade — before running from them again like lily-livered cowards.

At Independence Mall, it’s been 15 years. In 2002, I was part of the team of scholars and activists pressuring the park service to honestly interpret the history of George and Martha Washington as enslavers. Park management and staff had known of this history — and the general location of the President’s House where it occurred — since the 1970s.

Nevertheless, it remained reluctant to tell it at Independence Mall, where, as one park historian assured me, “We have 60,000 visitors every year from the South.” I wondered then whether he thought the visiting Southerners somehow didn’t know about American slavery.

The best option the park service had come up with was to relegate the story of the Washingtons and slavery to the Deshler-Morris House in Germantown. Sharing this history in a predominantly African American residential neighborhood seemed good enough to those making the decision … even though the Washington household had lived there for no more than a few months during the 1793 yellow fever epidemic.

But Black activists and public advocacy groups demanded a location with greater exposure, and after eight years of unrelenting effort to clear ever-more-imaginative roadblocks, the history made it into the public eye in 2010, on the site where the Washingtons lived in front of the modern Liberty Bell Center.

The President’s House site today is not all that it could have been, not by a mile, but it remains one of the most prominent monuments in the nation to openly acknowledge how much American liberty depended on African slavery.

That 15 years later, the truth is again under threat repeats a shameful American pattern.

From 1776 to 1787, we were a land trying to be born on the principles of the Declaration of Independence. But 11 years was enough liberty, it seemed, and we fell back to a constitutional design that protected and sustained wealth inequality and the slavery that sustained it. Eleven years, and it was back to the beginning.

Fast-forward to 1865, when slavery was legally abolished at the cost of “every drop of blood drawn by the lash paid for with one drawn by the sword,” in Abraham Lincoln’s eloquent and humble words. This time, too, national commitment to “liberty and justice for all” lasted 11 years.

That decade hosted an explosion of Black autonomy and achievement, with schools founded everywhere in the defeated Confederacy, voters in formerly Confederate states electing Black men to local, state, and federal offices, newspapers springing up all over North and South encouraging freed people toward education, land ownership, church membership, and entrepreneurship.

Black men and women gathered everywhere in conventions, successfully petitioning President Ulysses S. Grant and (less successfully) Congress for protection from white racist attacks designed to demoralize them and repossess their growing wealth.

» READ MORE: Under Trump’s assault, Black educators must preserve history | Opinion

After 12 years, the Republican Party agreed in the Compromise of 1877 to stop protecting Black civil rights with the U.S. Army, leaving white supremacist state governments to manage their own affairs.

By sacrificing Black safety, prosperity, and human rights, Republicans secured the presidency for Rutherford B. Hayes (the popular vote loser). White supremacists quickly disenfranchised Black men, seized Black-owned property, burned Black-owned schools, ramped up their campaign of lynching, and won endorsement from the U.S. Supreme Court for legal segregation.

Decades of Jim Crow oppression that followed could not undo the memories of those years of jubilee. Black-run schools continued to turn out courageous young people inspired with dignity, Black churches grew into communities capable of supporting change, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) kept up its relentless legal crusade against Jim Crow.

Violence pushed and economic opportunity pulled African Americans toward the Northern states, where new ideas and experiences, both bad and good, charged the fight for freedom. As it had in the revolution and the Civil War, military service gave Black men (and, at last, women) opportunities for education, homeownership, and proudly patriotic reasons to claim their country’s support.

In 1954, when the NAACP won the landmark ruling in Brown v. Board of Education that struck down legal segregation, and when the women and men of Montgomery, Ala., banded together to strike down segregation on their buses, the wheel began to turn again.

It took 10 years, bloodshed, great courage, and determination, but at last the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 rewrote the legal landscape of American race relations.

Also in 1965, the Immigration and Nationality Act offered enterprising people the world over the first opportunity not constrained by racial and national quotas to bring their strength and visions to the American Experiment. This change lasted long enough to generate backlash against both civil rights and immigration, mounting steadily since 1980.

Back home in Philadelphia, in 2010, Independence National Historical Park lived up to the ringing assertion that all of us “are created equal” and unveiled its acknowledgment that African Americans’ longing for liberty belonged in the nation’s “historic square mile.”

But it looks like 15 years of truth-telling will again be as much as we can stand. This is regressing. Trump is remodeling us into weak-kneed shiverers, liars who can’t even acknowledge the historical errors we have made.

So let us stand tall and ask, what on earth is disparaging to any Americans to say, as the panels at the President’s House do, that Ona Judge’s “strong desire for liberty” led her, at 22, to seize and hold her freedom, categorically rejecting enslavement to the Washingtons? Isn’t that what Americans pride ourselves on, our “longing for liberty” and the courage to seize it? Isn’t that exactly what we’re setting up to celebrate here next year?

What is inappropriately disparaging about noticing, as another panel does, that Black and white leaders together celebrated the raising of Black churches in our city? Why should anyone hang their head to learn that Benjamin Rush, one of the city’s leading white medical men, affirmed, “May African churches everywhere soon succeed”? What could possibly be more American than fulfilling the First Amendment right to religious liberty?

And who among us is too fragile to give thanks for the heroic efforts of Richard Allen and his team of generous Black citizens who stood up to cope with dead and dying Philadelphians of all sorts during the yellow fever epidemic of 1793? The only right response to their work is gratitude and honor. No one is disparaged by offering it.

Rather, in turning away from the truths of our history, we shame our ancestors. Our nation’s founders couldn’t see a path forward without legalizing the catastrophic moral error of slavery. Through multiple compromises that supported the slavery system, they kept the U.S. Constitution unsullied by the word slavery itself, leaving to later generations the work of fixing their founding error.

Now, one dishonest traitor convicted of 34 felonies tells us he wants us to silence the many voices that pushed the nation toward justice over its 250 years, and retreat from the truths we have worked so hard to bring forth.

If we do so, if we give an inch on this, we disparage only ourselves.

Sharon Ann Holt was the editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography when it published Edward Lawler’s findings about the President’s House inhabitants, location, and architecture in the January 2002 issue. In 2023, she retired from Penn State Abington, where she taught history and public history.