In moving All-Star Game from Georgia, MLB honors civil rights legacy of Hank Aaron | Will Bunch

In his quiet way, baseball great Hank Aaron spent a lifetime fighting racial injustice. Baseball's rejection of voter suppression honors his legacy.

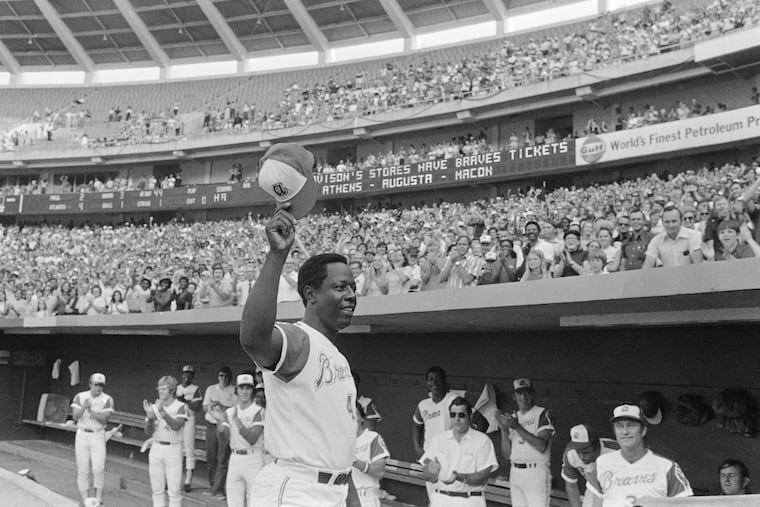

When I was a kid, I was blessed to watch Hank Aaron hit a baseball, albeit from the far reaches of the upper deck at Shea Stadium. The former Milwaukee and Atlanta Braves legend made the difficult art of batting look easy, and he would hit more home runs — 755 — than any other human being who did not ingest steroids. What I didn’t realize then, as a young baseball fanatic, is what didn’t come so easy for the soft-spoken Aaron — which was when and how to use his prominence as a Black superstar to speak out on civil rights.

According to Aaron’s biographers like Howard Bryant, the run-up before the Braves ultimately left Milwaukee for Atlanta in 1966 was a pivotal moment for the slugger, who’d begun following the civil rights movement and reading writers like James Baldwin. “I have lived in the South, and I don’t want to live there again,” Aaron said at the time, remembering growing up and then playing minor league ball in Alabama and Georgia at the height of Jim Crow. Weighing whether to play in Atlanta, he was introduced to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

King lieutenant Andrew Young told Bryant that Aaron said he was embarrassed he hadn’t spoken out more publicly for civil rights, but King — a big baseball fan, it turns out — offered absolution. He urged Aaron to move to Georgia and let folks like him and Young fight the political battles, so Aaron could do what he did best: hit homers. The man they called Hammerin’ Hank did exactly that, breaking Babe Ruth’s home run record on April 8, 1974, six years and four days after King had been assassinated in Memphis, Tenn. He did it despite a rising tide of hate mail from racist Americans furious that baseball’s new home run king was Black.

After he retired and stayed in Atlanta as an executive for the Braves, Aaron not only grew more outspoken on matters of race but expressed admiration for those who took risks for what they believed. He defended football’s Colin Kaepernick, banished from the NFL for kneeling during the national anthem to protest racial injustice, by saying the quarterback was “getting a raw deal,” adding he’d like to see more players join him.

Aaron died in January at age 86, but there was little doubt that his actions had bent the arc of the moral universe in the right direction. There was no more powerful symbol of that than last week’s bold decision by Major League Baseball — whose long, tortured, far-from-complete journey toward racial equity had unfolded during the Hall of Famer’s lifetime — to yank its 2021 All-Star Game (and its annual player draft) from the Braves’ new-ish billion-dollar playpen in the Atlanta suburbs, to protest Georgia’s new law that advances voter suppression.

When the MLB’s commissioner, Rob Manfred, said that baseball “fundamentally supports voting rights for all Americans and opposes restrictions to the ballot box” and that moving the game demonstrates the sport’s true values, he was echoing Aaron’s long road toward righteous activism. It was Atlanta baseball fan King, after all, who said, “A man dies when he refuses to stand up for that which is right.”

Baseball’s unexpectedly decisive action — which caused conservatives to lose their collective mind, with GOP lawmakers threatening to punish MLB by revoking its antitrust exemption, and the disembodied voice of Donald Trump to call for a boycott from exile in Florida — seemed a turning point, marking voting rights as the battle for the soul of post-Trump America. I think what’s really riled the political right over the pressure not just from baseball but from Georgia’s top brands like Coca-Cola and Delta is that they’ve put the focus on the Big Lie — that Trump’s 2020 loss was the result of massive voter fraud that never happened — but also on the Pretty Big Lies behind a Republican voter suppression drive in dozens of states.

A furious Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp — aided by some in the “both sides” wing of the mainstream news media — insists that critics have it all wrong about the voting bill that he rushed into law, signing it last month under a painting from a Georgia slave plantation, flanked by six white men as a Black lawmaker was arrested for knocking on his door. Kemp has pointed to one provision in the lengthy bill that allows some counties to expand early voting, offering a convoluted explanation of why his state needed to bar people from handing out water to voters in long lines, and accusing MLB and other critics of dishonesty — when of course it’s Kemp who is lying.

This weekend, the New York Times published a detailed analysis of what’s really in the measure. It found 16 different ways — making it much harder to vote absentee, or to use drop boxes or mobile voting centers — the new law “will limit ballot access, potentially confuse voters and give more power to Republican lawmakers,” and I’d encourage everyone to read it. This law is a meaningful step backward for democracy.

But there’s an even more powerful level of dishonesty here, and that involves the raw power of symbolism. Why are Republican lawmakers — not just in Kemp’s Georgia, but Texas, Arizona, and elsewhere — racing at warp speed to change their voting laws, after an election that saw record levels of turnout despite a pandemic? Simply put, the GOP is rushing to assure their own voters who were sold on Trump’s Big Lie that they’ve done something to address the fraud that never actually happened. And — as has always been the case with voter suppression efforts that date back to Reconstruction — they are also determined to convince Black and brown folks, the underprivileged, and young people that their votes won’t matter.

» READ MORE: Hammerin’ Hank Aaron protege Brian Snitker, Braves manager, gets caught looking past civil rights | Marcus Hayes

In other words, the images of white supremacy that Kemp carefully stage-managed in signing the bill were as significant as its actual provisions — arguably more so. It was depressing to see the usual suspects refuse to stand up for what is right, and thus die a little in the process. That includes Georgia’s recently failed Senate candidate Kelly Loeffler, who issued a ridiculous statement claiming that MLB had botched an opportunity to honor Aaron, and even the Braves themselves — a franchise whose own difficult history includes not just a name and traditions that dishonor Indigenous Americans but also ditching a perfectly good 23-year-old stadium in majority Black Atlanta to build a new one in a majority white suburb. The Braves said they were “disappointed” by the move, but anyone who believes in democracy should be disappointed in the Braves.

There’s no “both sides of the debate” when it comes to active voter suppression, and frankly, it’s been damn encouraging this last week to see so many leaders of corporate America and the sports world starting to get it. As it seeks a new home for July’s All-Star Game and plans its Aaron tribute, I’m rooting for MLB to do anything and everything to honor a man who rose above mere baseball immortality to become a great American. Hank Aaron may have hit hundreds of home runs, but this final grand slam is the one that traveled the farthest.

» READ MORE: SIGN UP: The Will Bunch Newsletter