Philly schools have had to make heartbreaking decisions for years

Did other children in better-funded districts have to say goodbye to their teachers because of a systematic policy rooted in disruption? You know the answer.

My first year of teaching in 2018, I was leveled. It was awful.

Leveling happens a few weeks into the school year, when district officials force teachers at schools with lower-than-expected enrollment to move to schools with too many students.

For me and my students, the experience was heartbreaking.

I had just been hired, so I was the last one in and the first one out of James G. Blaine, an elementary school in the Strawberry Mansion neighborhood. I found out via an automatic email from the district, which my more seasoned colleagues explained was “normal.”

I was forced to report to the district office after school and wait four unpaid hours to be told I basically had one option: the Edward T. Steel elementary school in Nicetown.

I got the email the day before my sister’s wedding and had to keep my cool all weekend as my family asked me how my new job was going. I smiled and said, “Good,” but nothing about what was happening was good for my students and the community.

My transfer left the other special education teacher with over 30 kids, far over the legal limit to have on a caseload, which ranges from eight to 20 kids. This process did not “level” anything at all — it just ripped a community from any sense of stability it could have had to save a quick dollar.

I didn’t know it then, but I’d end up happily calling Steel my home for the next six years.

But that doesn’t make up for what my Blaine students and I had to go through. I still remember their faces when I told my class I was being transferred. I tried explaining that it wasn’t my choice, but it didn’t matter. The result was the same: I was just another teacher abandoning them.

The experience was enough to make me nearly quit altogether, which I don’t say lightly. I love teaching and my students. Even amid a mass exodus of educators, I have no plans of leaving now.

So I am ecstatic that Superintendent Tony B. Watlington Sr. recently decided to end this controversial practice, after more than a decade of parent and community outcry against it.

However, leveling should have never even been an option. Equitable funding would have never put me and the Strawberry Mansion community through what the district put us through in 2018.

Leveling should have never even been an option.

For years, officials argued that leveling is the best and most efficient thing to do, to put teachers where they are most needed. In theory, this reduces teacher vacancies and is cost-efficient. However, in practice, this system damages learning across the whole school.

Removing a teacher from a classroom weeks after the school year begins is extremely disruptive to students, who have already built a foundation with their teacher. Research shows that students whose teachers leave midyear have lower test score gains than kids who get to keep the same teacher all year.

People may say leveling happens because of efficiency. But the real reason is inequity. Did other children in better-funded districts have to say goodbye to their teachers because of a systematic policy rooted in disruption? Or did they enjoy their teacher all year long, making growth and progress?

You already know the answer. Leveling doesn’t happen in places like Lower Merion or Swarthmore.

The funding choices we make in Pennsylvania — which have resulted in chronically shortchanged districts like Philadelphia — have stolen years of progress from our children.

» READ MORE: My parents didn’t let me apply to a magnet school. I’m glad. | Opinion

I’ve taught through the pandemic, substitute principals, and more. But the only thing that ever made me consider quitting was being leveled. The School District of Philadelphia nearly lost me altogether, and I am certain it has lost other teachers due to leveling.

Now that we are facing a nationwide teacher shortage, we need all the teachers we can get. We have vulnerable students who need teachers, and teachers deserve job stability. We need to continue to fund that stability like other, more wealthy districts are able to do. The deciding factor in stability in schools should not be zip code.

School funding directly affects students and families for generations to come; it is deeper and more personal than numbers on a page.

As we begin to dismantle unjust policies such as leveling and consider the implications of the 2023 court case that determined Pennsylvania’s system of school funding was “unconstitutional,” I can’t help but wonder: If this verdict had come sooner — say, before the fall of 2018 — would the students at Blaine Elementary have had to go through such a big disruption?

What else can we do with adequate funding? What could our children achieve with equitable funding? I would like to find out.

In the meantime, we need to protect the children of Philadelphia and other underfunded districts so that policies like leveling don’t return. We need our legislators to pass the proposed legislation that ensures an immediate “down payment” this year. It also locks in a seven-year timeline to ensure fully adequate and equitable funding, which allows our state to start on a path toward having enough money to properly educate our students. We cannot leave our most vulnerable students’ futures up to chance with any more disruptive and careless policies.

Even though leveling is gone, it should have never been implemented in the first place. We have work to do to make up for the effects of this devastating policy. Give our children a chance and fund stability in our schools.

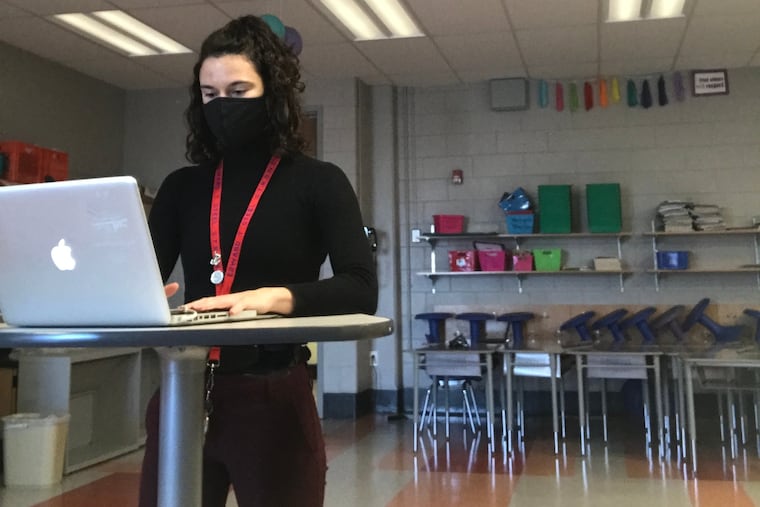

Nicole Wyglendowski is a Teach Plus Pennsylvania senior policy fellow and a special education teacher in the School District of Philadelphia.