Harvard public health dean: Voting is crucial for the physical health of our communities | Expert Opinion

Voting has always been one of our most potent ways to effect change in public health on a massive scale.

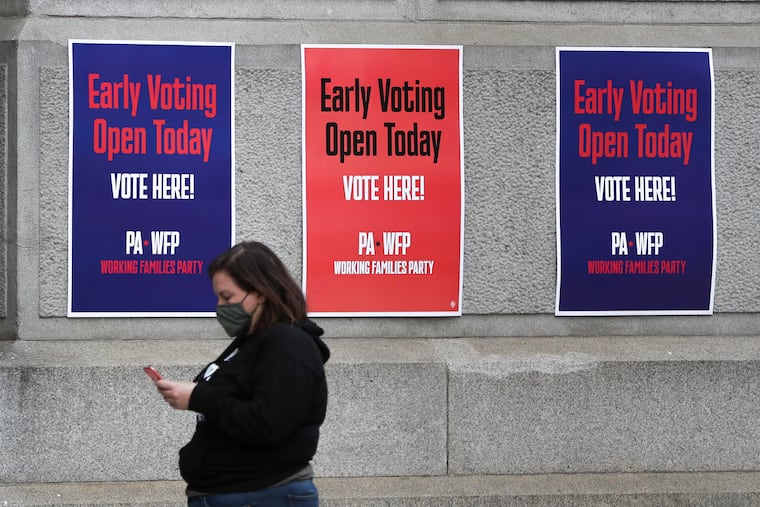

President Donald Trump’s COVID-19 diagnosis makes clear that this election cycle has the potential to impact the social determinants of health and harm individuals. With early voting well underway, it is crucial that the voters across the country understand that casting a ballot is vital for the physical health of our communities.

Research shows that voting leads to better overall health and well-being. When communities vote at higher rates, the people they elect are more likely to prioritize laws and policies that benefit them. The inverse is also true: The less accountable elected officials are to their constituents, the less responsive they become to their needs. And that can exacerbate existing health disparities.

We are at a time where health care is of the utmost importance. Voting cannot be under threat – there is too much at risk.

» READ MORE: Everything you need to know about voting by mail, or in person, in Pennsylvania

During the COVID-19 outbreak, one in five households in the United States reported it had been unable to get medical care for serious problems when needed; unsurprisingly, 57% of this group reported negative health consequences as a result. It’s a self-reinforcing — and often deadly — cycle.

That is exactly why voting has always been one of our most potent ways to effect change in public health on a massive scale.

It was pressure from voters in the 1960s and 1970s that led Congress to pass our nation’s bedrock environmental laws, improving public health and saving millions of lives by cleaning up the air we breathe and the water we drink. So many of the social determinants of health are on the ballot this year, from racial justice and economic equity to climate change and health care — as well as the fight for science itself.

And, of course, we’re headed to the polls amid a once-in-a-century pandemic. Sadly, voters no longer have to wonder what happens when our elected leaders and government officials neglect public health. We’ve all seen the catastrophic consequences throughout this crisis — from the collapse of rural hospital systems, to the lag in testing and tracing, to inconsistent guidelines around masks and reopening protocols.

Moreover, it’s the communities that are disproportionately bearing the brunt of this COVID-19 pandemic — Black and brown people in particular — who have historically faced the greatest barriers to voting. That’s not a coincidence. The historic disenfranchisement of voters of color is one of the reasons why we still stare down so many public health disparities, including those underscored by COVID-19. In taking a closer look across the United States, at least half of households in the four largest U.S. cities — 53% in New York, 56% in Los Angeles, 50% in Chicago, and 63% in Houston — faced serious financial problems during the COVID-19 outbreak. Furthermore, these problems mainly affected Black and Latino households.

This election is no different; COVID-19 could very well exacerbate voting disparities. For one thing, communities with high rates of coronavirus may have lower turnout, since the risk of going to the polls may be higher for voters in those districts. The very same neighborhoods also tend to have fewer polling places and longer lines as a result of racist voter suppression tactics. Add to that a chaotic patchwork of state rules governing vote-by-mail and absentee balloting, and we could have a voting-rights crisis of historic proportions on our hands.

» READ MORE: Black voters, the time is now to make your voting plan | Opinion

An important part of ending this crisis — and adequately preparing for the next one — requires us to finally begin to address the full range of social determinants that account for our nation’s vast health disparities. That means the public health community must recognize voting as another critical social determinant of health.

Sen. Kamala Harris, the Democratic vice presidential candidate, put it well at her party’s national convention: “When we vote, things change. When we vote, things get better. When we vote, we address disparities. When we vote, we address the needs of all people to be treated with dignity and respect.”

To that, I’d only add: When we vote, the world is a healthier place.

Michelle A. Williams is an epidemiologist and dean of faculty, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She is the Angelopoulos Professor in Public Health and International Development, a joint faculty appointment at the Harvard Chan School and Harvard Kennedy School.