As nonprofits face growing pains, the city must be careful with taxpayer money | Editorial

City Hall must ensure stronger vetting and oversight of fledgling organizations that are well-intended but lack practical experience.

Amid the surge in murders and shootings that plagued Philadelphia following the pandemic, City Hall directed millions of dollars to dozens of nonprofits to try to stem the violence.

But an Inquirer investigation in 2023 found the city’s $22 million anti-violence program devolved into a politicized process that steered funding to nascent nonprofits that were unprepared to manage the funds. A city controller’s report the following year backed the reporting.

Now, along comes another Inquirer investigation, this time detailing the rapid rise and financial struggles of a nonprofit that received millions in taxpayer funds from the same program.

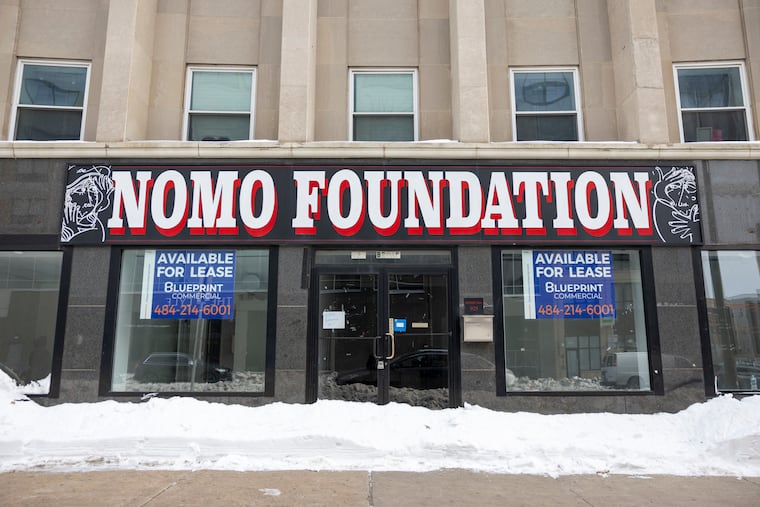

Soon after the nonprofit New Options More Opportunities, known as NOMO, received a $1 million grant to combat gun violence in 2021, city grant managers raised red flags about the lack of financial records and controls, the recent investigation by Inquirer reporters Ryan W. Briggs and Samantha Melamed found.

The story detailed a number of issues surrounding NOMO, including multiple eviction filings, an IRS tax lien, and five lawsuits regarding unpaid rent. But even as problems mounted, money from city, state, and federal sources continued to flow.

In a lengthy statement to the Editorial Board, Rickey Duncan, NOMO’s executive director, denied any wrongdoing. He said that NOMO “faced difficulties” several years ago, but they have been addressed. He stressed that all the funds received by his organization had been properly spent.

Since 2020, NOMO has received roughly $6 million in city, state, and federal funds. Duncan’s salary has increased from $48,000 to $145,000. His profile grew, as well: In November 2023, Mayor-elect Cherelle L. Parker named Duncan, a former volunteer at NOMO before he began leading the group, to her transition team.

According to The Inquirer investigation, NOMO was one of only two organizations in 2021 to get the maximum grant of $1 million, which was roughly triple its operating budget. The report found that a nonprofit the city contracted to manage the grant program raised immediate concerns that NOMO provided no balance sheet or audited financial statement.

Over the years, NOMO expanded its gun violence prevention efforts to include youth after-school programs and a short-lived affordable housing initiative.

At one point, NOMO leased an apartment complex near Drexel University’s campus at a cost of more than $500,000 a year. But it appears no one questioned how the housing plan fit with the organization’s core anti-violence mission, according to The Inquirer report.

In fact, the city tried to give NOMO more money. Last year, the city wanted to award NOMO a $700,000 contract for homelessness prevention, but the organization couldn’t meet the conditions, so the funds were not disbursed.

In January 2025, the city drew the line when Duncan tried to get reimbursed $9,000 for season tickets to the Sixers. He said the tickets were “an innovative tool for workforce development.”

But a grant program manager responded: “Season tickets to the Sixers are not an acceptable programmatic expense.”

The entire saga may underscore the need for stronger vetting and oversight of fledgling organizations that are well-intended but lack the practical experience to manage a program entrusted with hundreds of thousands of taxpayer dollars.

Adam Geer, Philadelphia’s chief public safety director, stressed in an interview with the Editorial Board that the Parker administration has implemented stronger oversight and support systems that did not exist when the initial anti-violence grants began.

He said those safeguards helped flag problems and put a stop to some of the spending that concerned city officials. Geer conceded there were “growing pains” when the anti-violence program launched, but he argued that nonprofits like NOMO played a key role in the steep drop in shootings in Philadelphia.

Duncan defended his organization’s anti-violence track record.

“There’s a reason why the city has continued to support the work NOMO is doing,” he wrote. “We are having a real, positive impact on people’s lives.”

Indeed, gun violence prevention programs can work — but the organizations charged with putting them in place must have the proper screening, support, and oversight.