The $20 million settlement against a racist mortgage lender should just be the start | Editorial

The sum is a pittance for the multibillion-dollar firm that owns Trident Mortgage. Prosecutors must seek harsher penalties as they continue their crackdown on "redlining."

The $20 million that Chester County-based Trident Mortgage has agreed to pay for its appalling redlining practices in Philadelphia and other communities is a hand slap.

Although touted as one of the largest redlining settlements in history, Trident’s $20 million penalty is a pittance for a company owned by Berkshire Hathaway, the giant conglomerate founded by Warren Buffett, one of the richest men in the world.

Berkshire is one of the most valuable companies in the world, with a market capitalization of more than $600 billion. While Buffett only paid himself $373,000 last year as CEO of Berkshire, his personal worth is around $100 billion. So $20 million is chump change for Trident’s racist actions, which read like something from the Jim Crow era.

Investigators found that between 2015 and 2019, Trident actively avoided issuing mortgages in Black and Latino neighborhoods. The 23-page federal complaint said the company maintained a nearly all-white staff that traded racist emails and racial slurs with real estate agents.

» READ MORE: DOJ reaches ‘historic’ redlining settlement with Philadelphia mortgage lender

One email depicted a photo of a wheelbarrow full of watermelons with a sign that read: “Apply for a credit card. Free watermelon.” The subject line read: “You know when you’re in the hood.” Another depicted a Trident senior vice president posing in front of a Confederate flag. A Trident loan officer discussing a customer seeking prequalification for a loan said to a colleague in an email: “This one is in the ghetto.”

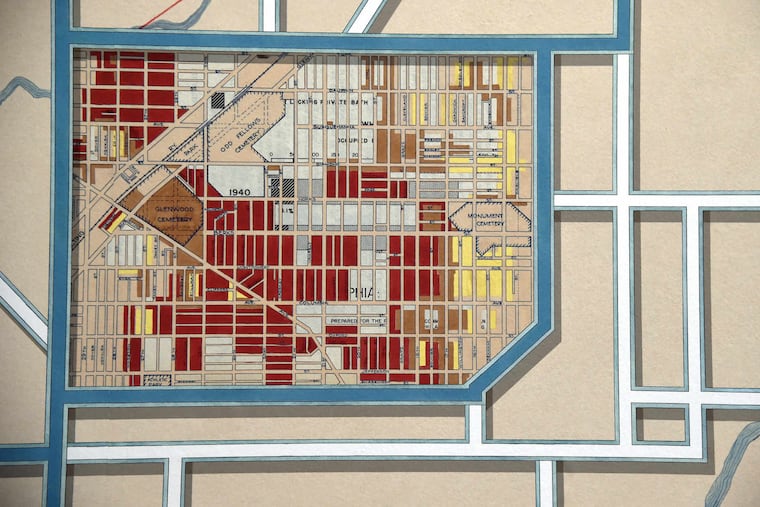

Trident denied any wrongdoing, but its appalling behavior goes beyond the racist comments of its employees. Trident’s alleged lending pattern is a sad reminder that redlining never stopped. The practice dates to the 1930s, when government maps drawn by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corp. marked neighborhoods in red if mostly Black people lived there to avoid making loans to them.

Redlining was outlawed in 1968, and the Community Reinvestment Act in 1977 required banks to invest in poor communities and lend to low-income individuals, but those moves haven’t done enough.

Trident is not an outlier, but rather part of a sick, disturbing, and illegal pattern that should have died decades ago and hurts everyone in the long run. A 2018 report by the Center for Investigative Reporting found Black and Latino mortgage applicants in Philadelphia and 47 other cities continue to be denied conventional loans at rates far higher than their white counterparts — even when the applicants’ incomes, loan amounts, and neighborhoods were similar.

“Barriers to homeownership are part of the decades-long systemic racism that has prevented people of color from building wealth.”

Barriers to homeownership are part of the decades-long systemic racism that has prevented people of color from building wealth through home equity, the biggest driver of wealth creation. That difference helps explain why the average white family in the United States is about 10 times wealthier than the average Black family.

In Philadelphia and across Pennsylvania, the homeownership gap between white Americans and Black Americans has widened since 1990. Last year, City Council announced plans to invest $400 million in programs to support affordable housing, provide for home repairs, and help first-time buyers. But more must be done to increase homeownership among people of color. Some solutions include providing help with down payments and closing costs for first-time buyers living in redlined neighborhoods.

Prosecutors must also continue to crack down on lenders that redline, seek harsher punishment if they are found guilty, and steeper prices if they agree to settle. And $20 million is not nearly enough.