The latest mishandling of MOVE remains is an outrage — and an opportunity

Only unrelenting public pressure can truly transform reckonings from apologies to atonement, from plans to deeds, from trauma to the kind of truths that can lead to some healing.

It was the callous use of the word dispose to describe how the city handled the remains of Black Philadelphians murdered in the MOVE bombing in 1985 that sent chills down my spine.

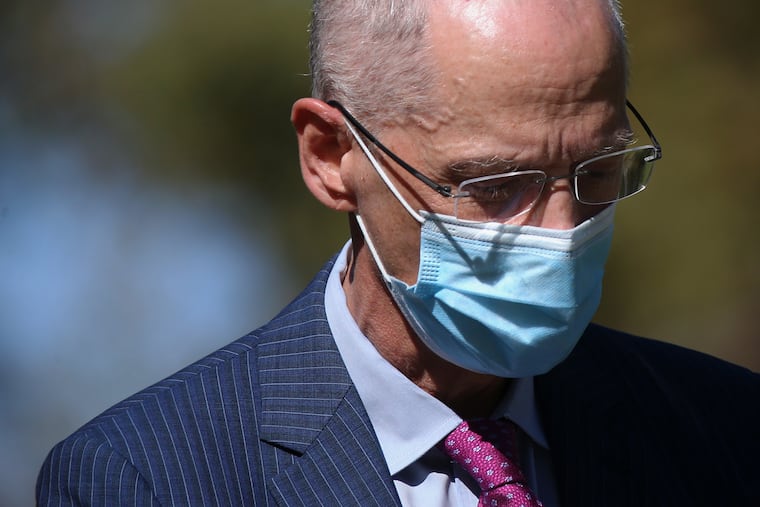

In a statement about the health commissioner’s sudden resignation, Mayor Jim Kenney this week said: “Instead of fully identifying those remains and returning them to the family,” Thomas Farley “made a decision to cremate and dispose of them.”

Farley later issued his own statement, calling his decision a “terrible error in judgment.”

“Believing that investigations related to the MOVE bombing had been completed more than 30 years earlier, and not wanting to cause more anguish for the families of the victims, I authorized [Medical Examiner] Dr. Gulino to follow this procedure and dispose of the bones and bone fragments.”

What that meant exactly was unclear, and the fact that at a hastily called news conference on Thursday neither the mayor nor Managing Director Tumar Alexander could — or would — clarify what happened signaled we should brace for even more appalling revelations.

But who would ever have imagined it was the torturous twist that came on Friday night? Turns out that the remains were not destroyed, a lawyer for the family said. A subordinate had apparently disobeyed Farley’s order in 2017, said Leon A. Williams, an attorney for the family of the MOVE victims. (Though who knows what the story will be once we know all the facts.)

A relief, of course. Cause for celebration? Only if you don’t consider the trauma on top of trauma on top of trauma heaped on the surviving members of the Africa family that formed MOVE.

(And this, just a month after Penn Museum apologized for using bone fragments from one girl killed in the bombing as a “case study” for research and testing.)

It’s an outrageous new chapter in one of Philadelphia’s worst atrocities that leveled more than 60 homes in West Philadelphia and killed 11 people, including five children.

It’s also an opportunity — maybe the best opportunity the city has to finally and fully acknowledge and atone for the atrocities of its past.

We can start with the Africa family, and getting into the same room everyone responsible for inflicting their lifelong pain — politicians, police, firefighters, researchers — and hearing them out, whether that takes two hours or 200.

It’s time to listen to them, on their terms.

Get comfortable being uncomfortable, because every part of this dark passage in our past, and now our present — including the family’s gutting decision to announce the latest revelations on the 36th anniversary of the MOVE bombings — is hard and uncomfortable and traumatizing.

In an opinion piece published in The Inquirer this month, Shannon McLaughlin Rooney, who spent years researching and writing a doctoral dissertation on media coverage and public memory of the bombing, called for a second MOVE commission.

“What does it mean to remember and reflect on a tragedy we never properly understood, aspects of which are still in dispute?” she wrote.

It means we end up here. Apologizing again, and again — sometimes even for more missteps that thankfully weren’t taken, though not because those in charge chose to do the right thing. On Friday, Kenney said that Sam Gulino, the city’s medical examiner, presented Farley with two options after the remains were discovered in cardboard boxes in a storage room: Return the remains to family members or dispose of them.

We know what Farley chose, and even if someone made the right decision to disobey him, he has no business being the top doctor in this city.

To move beyond this point is going to take action, and not from suddenly sympathetic politicians. Last year, Kenney and Council President Darrell Clarke were both silent on whether the city should apologize for the MOVE bombing.

Only unrelenting public pressure can truly transform reckonings from apologies to atonement, from plans to deeds, from trauma to the kind of truths that can lead to some healing.

We’ve had a few of those moments recently — even if the city has had to be dragged to act. (These are only the days of reckonings, after all, not miracles.)

Think of the 2020 homeless encampment on the Ben Franklin Parkway and how the organizers there got what they needed from a city notorious for saying “We’ll sure try to work on that, folks!” They wouldn’t relent to empty promises, and after months of negotiations with the city and federal housing officials, a historic deal was struck to provide permanent housing for residents.

Think back, too, on a smaller scale, to 2018 when the two Black men arrested for sitting at a Philadelphia Starbucks without ordering anything settled with the city for a symbolic $1 each and a pledge from officials to set up a $200,000 program for young entrepreneurs that has since been piloted at two Philly high schools.

In and out of Philly, there are growing examples of the kind of renegade, enough-is-enough, not-gonna-take-it-anymore movements it takes to bend institutions toward justice.

It’s been 36 years, but now can be the time.