‘Please take pictures’: Philadelphia moms who lost children to gun violence don’t want us to look away | Helen Ubiñas

Kathy Shorr hopes that what began as a project to highlight the enduring grief of so many mothers will grow into a call to action and activism.

Kathy Shorr, a New York City-based photographer, spent nine months photographing 51 mothers whose children were killed by guns in the Philadelphia area. Shorr was encouraged to photograph the mothers by a Philly resident whom she had photographed for an earlier project about gun violence. But once Shorr met these women, she was committed to using her camera to tell as many of their stories as she could. What began as a photo project to highlight the agonizing pain of mothers devastated by violence, Shorr hopes will grow into a call to action — led by the women who’ve lost the most.

I spoke with Shorr about her project “SHOT: We the Mothers.” Her answers have been edited for clarity.

Tell us a little about your photography.

I consider myself a hybrid documentary, portrait, and street photographer.

And what does that look like?

In 1989, I drove a limousine for nine months in New York and photographed everybody that I had in the car. I did something on ballroom dance before that. And I’ve done work in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where part of my family had immigrated in the late 1880s. So, I did a project at the house where my great-grandparents had come, 63 Scholes Street, about the changing face of Williamsburg. That was fun to do because I was learning about my ancestry and I was also learning a lot about this neighborhood, the other Williamsburg, not the trendy part but the part where immigrants go, which is still continuing to this day.

This isn’t the the first project that you’ve worked on that touches on the raw, emotional toll of gun violence. Tell me about “SHOT: 101 Survivors of Gun Violence in America.”

In 2013, I decided I wanted to do a long-term project, and I thought about survivors of gun violence. The people who were thought of as lucky, because they had survived. I myself have been robbed at gunpoint. It’s not something I think about all the time, but I had that inside of me when I was working on the project.

» READ MORE: In their own words, 7 moms whose kids were killed by gun violence share what they’ve lost | Helen Ubiñas

So, how did you approach the project?

I thought in order for this to be successful, I have to have all kinds of people from all over America, in all kinds of circumstances. I have to have gun owners and people that hate guns. I have to have an extremely diverse project.

It sounds challenging, to try to cover that much in one project.

In the middle of the project, someone from Slate magazine had gotten in touch with me and said they heard that I was doing this project and would I be interested in putting some images up on the site and I was like, “Wow, I never thought this was going to happen before I finished, but sure.” Once the story came out, it kind of went viral and so the survivors toward the end were actually calling me and asking if they could be in the project. I finished the project in 2015. The book came out in 2017. It just kind of kept going, and people were very interested in it. It resonated on so many levels.

Tell me about the people you photographed for that project.

I was just amazed at the stories of survival. People would always ask me, “Of all the people that you photographed, which one really resonates with you?” All the stories stay with me. I can’t pick one person or one story over any other, but the one issue in the project that really disturbed me the most was domestic violence. And 20% of the women who are in the project were shot because of domestic violence.

Did you plan on continuing to pursue the topic of gun violence in your photography?

After the project, people would say to me, “Oh, you’ve got to keep doing things about gun violence. We need this.” And I was like, “No, I think I’ve really said everything I have to say in this project.’ I felt that I had made a statement, and the statement was that this affects everybody in America, no matter who you are or where you are, and we have to come together and work on this together.”

I felt that I had made a statement, and the statement was that this affects everybody in America.

Movita Johnson-Harrell, whose son Donté was killed last March, was the first mother in Philadelphia photographed for this project. How did you approach her and the other moms?

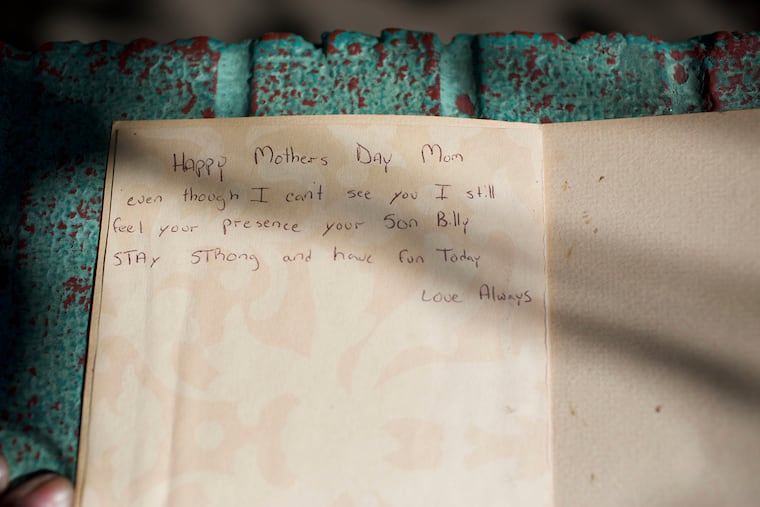

I wanted to photograph at a place that had some meaning to the child who had passed away, because I felt that the energy of that connection would make them more of a person than a photograph. I would also say, “Can you please bring something that had significance to your child?” So, she had Donté's hat with her. She brought this hat out, and she said to me, “I have to smell him. I need to smell him. I need to feel him,” and she started, you know, sniffing the hat and started to cry, like really cry, and I stopped taking pictures. I felt like it was too intimate. I felt like I shouldn’t photograph this. And she said to me, “You must photograph. This is how I’m feeling, you have to photograph. Please take pictures.”

You’ve finished photographing the mothers, but it sounds as if you’re still working out how exactly you’d like to present them. Do you have any ideas?

I think that this could be a really interesting way to connect people in Philadelphia with the moms by putting up vinyl banners or vinyl photographs from the project around the community. I think it would be a really powerful statement to see them around Philadelphia. It’s a way of having more people see, again, because to me, gun violence is always so abstract, and when we put a face on it, it makes more people realize that it’s everywhere. We’re getting numb to it. So I think it constantly has to be put out there, that, you know, that person that you shot the other day, you might not even think about them, but here’s their mother, maybe you’ll think about that. How would your mother feel to be up on one of these posters?