This Mother’s Day, meet a woman who raised her nine siblings after their mom died

Mother's Day should be for all who mother, whether or not they gave birth.

Late last month, U.S. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene got something really wrong.

During a conversation April 26 with Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers, at a House hearing on school closures during COVID-19, the Republican congresswoman from Georgia asked Weingarten if she was a mother.

“I am a mother by marriage,” Weingarten responded. Meaning: She is a stepmother, like I am.

Greene replied sarcastically, “By marriage,” before letting Weingarten know she doesn’t think that counts. “The problem is people like you need to admit that you’re just a political activist, not a teacher, not a mother, and not a medical doctor.”

It was a nasty moment. And it was insulting to stepparents, grandparents, and others who open their hearts and homes to help raise children.

Rep. Greene is just plain wrong.

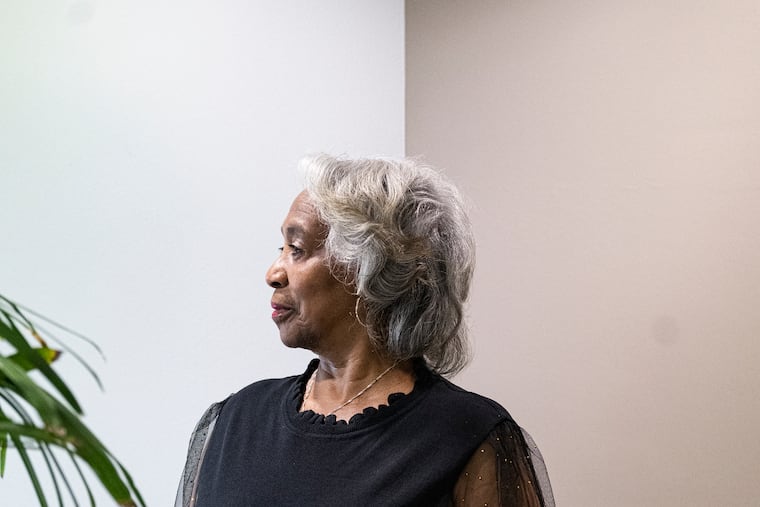

She — and anyone who agrees with her — needs to meet Barbara Sowell.

At age 19, Sowell was barely an adult herself when she became a parent to her nine siblings — yes, nine! —following the death of their mother at age 39.

Before she died, Sowell’s mother asked her to keep the family together at all costs. Sowell was a loving daughter who never considered doing anything other than following her mother’s final wishes. And that’s what she somehow did, managing to stay inside their apartment at the Richard Allen Homes in North Philly, despite her relatively young age.

“She would say, don’t separate her children. ‘Keep them all together,’” Sowell, now 80, recalled about her mother. “I tried to do what she requested.”

Despite the occasional “you’re not my mother” backtalk, raising her siblings wasn’t as difficult as it might have been, Sowell told me, in part because her mother provided her large brood with clear expectations. The late Dorothy Rose used to gather her children together on a single bed on Saturday mornings before chores to discuss the importance of becoming educated and good citizens. By the time she died, the older ones knew what they were supposed to do: church on Sunday, graduate from high school, and — above all else — stay together.

“I never found it to be difficult to raise or encourage my brothers and sisters, who had already been embedded with all of these little things that they probably never put together until they got of age,” recalled Sowell, who graduated from William Penn High School for Girls in 1961. “I think we all kind of lived that dream, like, ‘OK, Mommy would want us to do this.’”

One of the conditions of Sowell being able to stay in public housing at the time, she recalled, was that she get on welfare, which she did to supplement her mother’s government pension. After she turned 21 and was able to access what was left of her mother’s insurance policy, Sowell purchased a rowhome for the family on 79th Avenue.

“I didn’t see it as a hardship at all,” she said. “All I saw was trying to finish my mother’s dream, and trying to make sure that we all stayed together.”

Back then, older naysayers used to tell Sowell that she would never find a husband because of all the children in her care. Sowell proved them wrong. In 1966, she married Howard Sowell, a tall, handsome salesman for the Tasty Baking Co., who she’d first spotted playing basketball on Boathouse Row and later connected with at Barber’s Hall. A photo from their 1966 wedding shows her dressed as a bride on her wedding day and surrounded by her siblings.

After she became a wife, she moved her youngest siblings into her husband’s home at 22nd and Fairmount. The older ones — who by then were old enough to fend for themselves — stayed behind at the house on 79th Avenue.

The Sowell family expanded to include three of their own children. The family eventually settled in Cheltenham Township, where Sowell now lives. Howard died in 2005.

These days, Sowell has nine grandchildren including Donta Rose, an engineer who last summer opened a Grocery Outlet in Sharswood, and three great-grandchildren. It’s still a close-knit family; they often gather at her sister Donna Gardner’s house, who was only 12 when their mother died. “A holiday didn’t go by that we didn’t celebrate when my mother was alive. We still do the same thing,” Gardner told me. “It’s always a crowd.”

I decided to share Sowell’s story for Mother’s Day to celebrate those of us who become mothers through nontraditional routes. Even though I have never given birth, I’m a stepparent — and no matter what Marjorie Taylor Greene says, that counts.

We need to expand the definition of what a mother is and make the term more inclusive of everyone who loves on us — aunties, teachers, and grandparents, among others. It takes a special kind of person to raise other people’s biological children the way that Sowell and so many others did, and continue to do.

Mother’s Day is as much for us as it is for everybody else.