Keeping score at the ballpark ‘a lost art’ but still part of the baseball experience for many

Put your phone down and pick up a pencil and paper scorecard? The analog ritual "plays into the experience of a ballgame."

Caleb Leader and his dad, Dale, recently had seats that faced the enormous left-field scoreboard at Citizens Bank Park, which carries every updated statistic imaginable during a Phillies game, including the size of the pot for the 50/50 raffle.

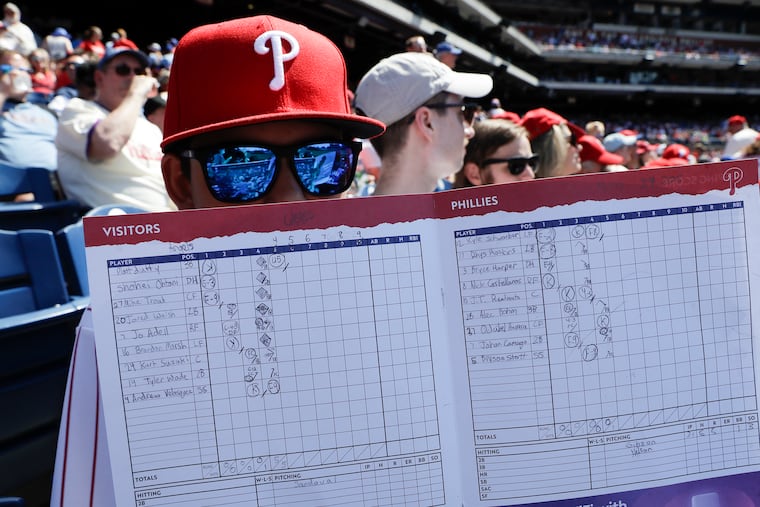

Caleb, 14, wanted to keep score anyway. Wearing a red Phillies cap and a pin-striped Bryce Harper jersey, he kept his official $3 Phillies scorecard in his lap, dutifully marking the proper boxes with a mechanical pencil, even logging details of how each pitcher did.

» READ MORE: As the Phillies play without Harper, Pat Gillick recalls 2007 trade for Chase Utley’s fill-in

“I think it’s just a fun way to keep track of a game,” said Caleb, who lives in Yardley and is a student at Calvary Christian Academy. “I just like the idea of having memories, so when I get older, I can look back.”

You don’t see too many fans who keep score at Phillies games these days. Mike Mulherrin, a 23-year-old Temple student and Mayfair resident who is in his first year selling scorecards at a stand inside the third-base gate, estimates that he sells 30 to 50 per game.

“With people’s attention spans so much shorter than they were, I still can see people getting a scorecard and keeping themselves entertained during a game,” he said.

He sells other items — $10 team yearbooks, $6 photo card sets, $5 Phanatic activity books — but the big sign across the top of the stand hawks the cleanup hitter in the lineup: GAME DAY SCORECARDS. Each comes with a red Philadelphia Phillies pencil, no eraser.

Mulherrin, wearing a Phillies cap and a gray shirt with “Publications” on it, pitches his product hard to the hundreds of fans who pass him in the main concourse. He already has a hearty chant that carries over the hustle and bustle: “Programs! Scorecards! Yearbooks!”

“You got a four-hour game and you spend money on a ticket, you don’t want to be on your phone all the time,” he said. “I also feel like it plays into the experience of a ballgame.”

» READ MORE: Inside the Phillies’ honoring of their first African American player, John Irvin Kennedy

And that pretty much explains why the Phillies sell scorecards in these days of instant information overload. They update the 12-page scorecards eight to 10 times a year. The Phillies won’t say exactly how many scorecards they sell, but that is not really the point.

“We like to keep the tradition alive,” said Phillies director of promotions Scott Brandreth. “Keeping score has been a staple of the ballpark experience for over 100 years, as has the vendor hawking scorecards and yearbooks. It’s part of the sights and sounds of game day.”

Moreover, keeping score, using much of the unique shorthand (or hieroglyphics) developed by sportswriters 150 years ago, has been the way for decades to participate in a game, even to those listening on the radio or watching on television.

“No other American sport has anything that genuinely approximates the scorecard — that single sheet of paper, simple enough for a child — and that preserves the game both chronologically and in toto with almost no significant loss of detail,” Thomas Boswell, the noted baseball columnist for the Washington Post, wrote in 1979.

The average length of a big-league game back then was a tidy 2 hours, 35 minutes. Now, an average game drags on for 3 hours, 7 minutes. The Phillies are good at playing games that take a long time. Eight of their first 38 home games this season lasted more than 3½ hours. A week into the season, the Phillies and Mets completed a nine-inning game in 4 hours, 4 minutes. An 11-inning game against the Giants on May 31 lasted 4 hours, 52 minutes.

“Baseball games have a lot of down time,” said Bob Plick, a Newtown Square resident who attended a recent game with his daughters, Ashley and Jenny. “If you don’t have a purpose, you tend to lose focus.”

» READ MORE: It’s almost time for the Phillies to focus on 2023 and beyond. Almost.

So Plick bought a scorecard before his family found their seats. So did Will Shipley, a Malvern resident who was attending the game with his young son, Liam. Shipley bought the scorecard mainly as a souvenir for his son, but he called keeping score “a lost art, in a sense.”

Looking down at his son, Shipley said, “I’ll teach him how to do it. I did it growing up, but I haven’t done it in a while. He’s just getting into baseball right now.”

Will Shipley is likely to teach his son a version of the system that has been used forever, with players’ positions in the field labeled from 1 to 9 and little diamonds in the center of each square in the scorecards marking a baserunner’s progress and filled in for a run scored.

Paul Dickson, who in 2007 wrote a book called The Joy of Keeping Score, once said the cheaper the seat in a ballpark, the more likely the person sitting in it would be keeping score. Many scorers are women, because mothers are recruited to score Little League games.

“You’re taking the game on your own terms,” he said in a 2018 podcast.

» READ MORE: Phillies’ Darick Hall thought his hotel was being robbed. Instead, he was being promoted to the majors.

Any scorekeeper quickly learns to use the letter “K” to represent a swinging strikeout (and a backward “K” for a called strikeout). The “K” symbol dates to the mid-1800s, when a sportswriter named Harry Chapman was developing a system for scoring games.

“His original system used only single letters,” reads an explanation on MLB.com, “and Chadwick couldn’t use ‘S’ for ‘struck’ (the preferred term of the time period) because it had already been taken by ‘sacrifice.’ So instead, he decided to go with what he thought was the word’s most memorable sound: the letter K.”

Phillies fans don’t have to keep score because the Phillies do it for them. Besides posting statistics on each batter, and the pitcher facing him, the scoreboard recaps how the batter did in each at-bat that day. The actual score of the game takes up hardly any room.

Phillies fans at Connie Mack Stadium were lucky to get the score line, the count and outs, batting orders and out-of-town scores on the big right-field scoreboard crowned by a Longines analog clock and the majestic Ballantine Beer sign (and its three-ring logo).

» READ MORE: The making of an icon: How Chase Utley became 'The Man' for the Phillies

The scoreboards at Veterans Stadium were a little more sophisticated, with a few updated stats next to a very grainy headshot of the Phillies batter at the plate. The scoreboards at Citizens Bank Park have all that, and then some — like the speed (and type) of the last pitch. But they still use the “K” and backward “K” to mark strikeouts.

Olivia Venier, 22, a Lawrence Township, N.J., resident who came to a game with her partner, Jesse Sacchetti, bought a scorecard and planned to fill it in and keep it in a box. Her great grandfather, Frank McCormick, played in 150 games for the Phillies after World War II.

“Any time I can get a scorecard or a program, I’ll do it,” she said. “I love doing that.”

Dale Leader, who was wearing a sky-blue vintage Phillies jersey with Mike Schmidt’s name and No. 20 across the back, said his son Caleb has been scoring games since he was 5 or 6. Dale smiled when he said, “It’s part of the learning process as a player.”

It has other benefits. They go to five or six Phillies games a year and stay until the last out. As other fans climb the aisles to leave the ballpark, they stay until his son completes his scorecard. It is a chance for father and son to mark another ballpark visit, alone and together.