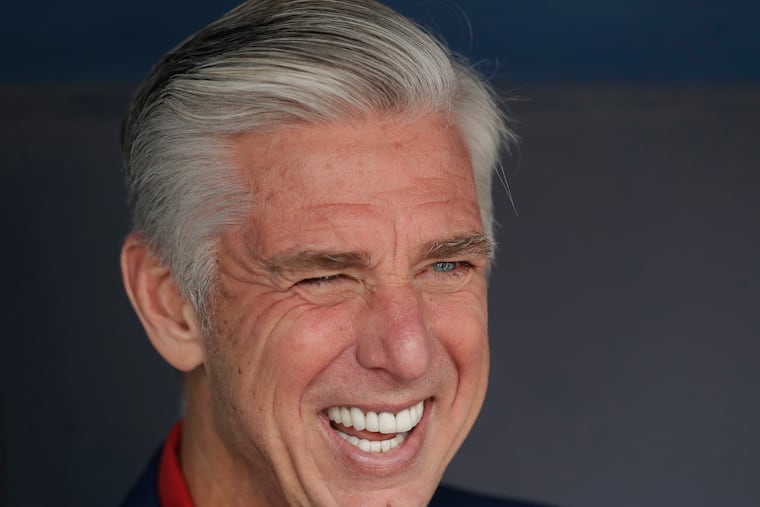

Dave Dombrowski’s creativity will be tested as he looks to make the Phillies a winner | Scott Lauber

After taking teams to the World Series in Detroit and Boston, Dombrowski left those organizations in varying states of flux and disrepair. Can he build something in Philadelphia that lasts?

Five years ago, the Boston Red Sox needed a closer.

They got Dave Dombrowski.

Hired to add elite big-league talent to a young nucleus and push the team from the 20-yard line into the end zone, Dombrowski delivered for New England like Tom Brady. He threw money at free agents, handed off prospects in blockbuster trades, and marched the Red Sox to three consecutive division titles and a World Series triumph in 2018.

But a year later, ownership decided he wasn’t the person to lead a longer-term transition and fired him in the middle of a game, 11 months after winning a championship.

Maybe that’s how Dombrowski’s reputation, formed over nearly 40 years, hardened like cement. There’s no denying that he’s a winner, having built World Series teams in three cities. But he left his last two teams, the Detroit Tigers and Red Sox, in varying states of flux and disrepair. After the abrupt ending in Boston, he was painted as a win-now cowboy who lacks vision beyond his own nose.

So, in the week since the Phillies gave Dombrowski a four-year contract to run baseball operations, reaction on social media has been mixed. Yes, Dombrowski gets results. But does his process yield sustainability beyond one roster cycle?

“It’s sustainable for a period of time, but I really think it’s all a function of what’s the mission statement of your organization,” said Frank Wren, Dombrowski’s inner-circle lieutenant in Montreal, Florida, and Boston. “Are the expectations that we’re going to compete for a World Series every year? You have to have buy-in of ownership to reach that point. If you have that, then it’s a doable process.

“But what happens with a lot of teams is the urgency kicks in that impacts your sustainability of winning year in and year out.”

Such urgency existed for Dombrowski in Detroit and Boston. It doesn’t seem to be the primary driver in Philadelphia. At least not yet.

The playoff drought

The mandate during the latter half of Dombrowski’s 14-year Tigers tenure was to win a World Series for owner Mike Ilitch, who was in his 80s. Ilitch approved annual payroll increases beginning in 2012, the second year of a four-year division-title run, and Dombrowski signed big-ticket free agents such as Prince Fielder and meted out extensions for Miguel Cabrera and Justin Verlander that totaled $428 million.

In Boston, after back-to-back last-place seasons, owner John Henry directed Dombrowski to reach the World Series quickly. Henry approved the $217 million signing of free agent David Price and didn’t object to unloading four prospects for closer Craig Kimbrel.

It’s not clear how aggressive Phillies managing partner John Middleton wants Dombrowski to be at the outset. Given the financial impact of the coronavirus pandemic, ownership intends to scale back a payroll that almost reached the $208 million luxury-tax threshold this year. But the Phillies haven’t made the playoffs in nine years, a drought that Middleton is itching to end.

“You can be successful for periods of time and then there’s going to be a lull where you’re not going to be able to replenish your system,” said former Phillies general manager Ruben Amaro Jr., a coach for Dombrowski’s Red Sox in 2016-17. “It’s very, very difficult to work both ends of the spectrum as far as development at the minor-league level and then have great success long-term at the major-league level. And different cycles deserve different types of moves.

“Dave has had success doing exactly what it is that he’s been championed to do. He’s done rebuilds. He’s been in situations where he’s asked to have quick success. He’s had the ability to do all those things.”

The Phillies in 2020 have neither the homegrown core nor the ripe farm system of the 2015 Red Sox. And Dombrowski and Middleton seem to agree that the team is more than one player away from the World Series.

But the Phillies also aren’t the 106-loss 2002 Tigers. If there’s a comparable situation from Dombrowski’s past, it may be the 2011 Tigers, who morphed from playoff outsiders into a 95-win division champion in two offseasons with sage signings (closer Jose Valverde, shortstop Jhonny Peralta, DH Victor Martinez) and brilliant trades, including a three-way deal for Max Scherzer and center fielder Austin Jackson.

With the Phillies, Dombrowski can’t succeed by throwing money and prospects at every problem. His creativity, doubted by the Red Sox, will be tested.

“The task is not going to be easy for him,” Amaro said. “As an executive, I’m sure he would love to be in the position to make that team win ASAP, but it’s obviously been pointed out that this may take a little time. It seems that Dave was willing to do this under the circumstances.”

Prospect lovers need not fear, then, that Dombrowski is about to raid the Phillies’ farm system. It’s true that he once traded Randy Johnson for Mark Langston and more recently turned Yoan Moncada and Michael Kopech into Chris Sale. And he has won far more trades than he’s lost. You can check his record.

But he appears to realize that the Phillies need to add cost-controlled young players to the organization, not use them as trade bait.

Wren also defended Dombrowski’s record of trading prospects, noting that he has a knack for retaining the right ones. In Boston, for instance, he thinned out the farm system but also drew the line at including third baseman Rafael Devers and outfielder Andrew Benintendi in the Sale trade.

“When you’ve been a general manager as long as Dave has been a general manager, you understand what the roster makeup needs to be, what the organization needs to do overall,” Wren said. “He understands that role probably better than anyone in the game, and he’s able to have the vision to see what he needs to do to accomplish the goal.”

Winning now vs. building for the future

Dombrowski’s bigger flaw might be not knowing when to cut ties with players. If he’s excessively sentimental, he has a good reason.

After building the 1997 World Series champion Marlins, Dombrowski was directed to orchestrate a massive offseason fire sale. A year later, the Marlins lost 108 games, hardly a robust title defense.

With the Red Sox, he went the other way. Even as ownership wanted to lower the payroll under the luxury-tax bar, Dombrowski signed Sale to a $145 million extension despite health concerns after the World Series and brought back Nathan Eovaldi and Steve Pearce when it seemed more prudent to move on, moves that all but forced the Red Sox to trade star right fielder Mookie Betts.

The Tigers were similarly handcuffed by Cabrera’s eight-year, $248 million extension, which continues to limit their rebuilding project.

But that’s the tradeoff, according to Amaro, for a winning run.

“You’re asked to do ‘X’ and you get there, and at some point you’ve got to pay the piper,” Amaro said. “You do your job and try to win and not necessarily try to build organizations. That’s part of it and certainly an important part, but really the end game is to win and David knows how to do that.

“He’s shown in the past that he can do both. He can build and he can put the finishing touches on a club. The Phillies are somewhere in between right now.”

And if Dombrowski has a blind spot for not always building the most sustainable winners, the Phillies will happily deal with it later.

They have to actually win something first.