The Phillies were accused of using technology to steal signs 117 years before the Astros

Seen from a secret vantage point in center field, the signs were relayed via hidden wires to a battery-powered device buried beneath the third base coaching box.

While many in baseball continue to urge harsh penalties, the Houston Astros might want to cite historical precedent as a defense for their sign-stealing.

After all, when an earlier baseball generation uncovered — literally — a sign-stealing scheme that used technology to tip off hitters, the 1900 Phillies got off scot-free.

While sign thievery was an accepted aspect of the game, the Phillies’ system was so devious that even this city’s then boosterish sportswriters denounced it.

“This may be honest baseball,” wrote one, “but the general public has nothing but contempt for people who play with marked cards.”

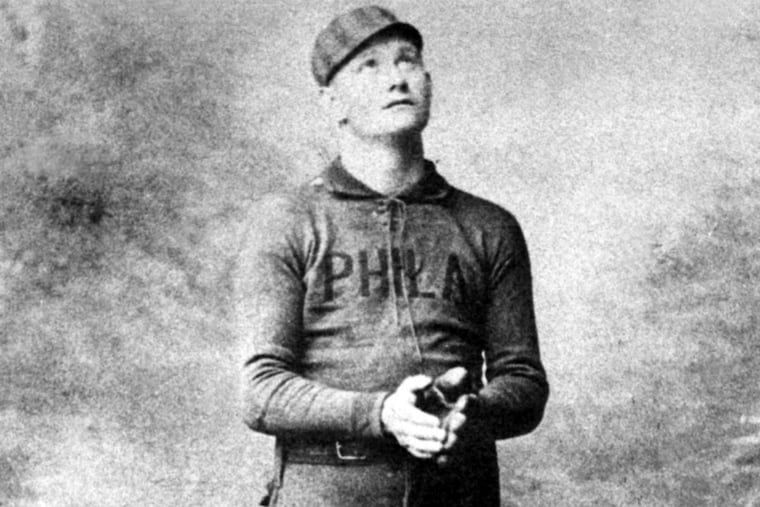

Managed by Bill Shettsline, previously their ticket manager, the 1900 Phillies were a decent ball club. Though they were short on pitching, their lineup featured three future Hall of Famers — Ed Delahanty, Nap Lajoie, and Elmer Flick. They finished third in the National League standings (75-63), second in hitting (.290), and, though they averaged just 4,313 fans a game, first in attendance.

How much their elaborate thievery contributed to that success will remain a mystery. But it’s interesting to note that those Phils, 30-40 on the road, went 45-23 at home. And their best hitter, Delahanty, batted 80 points higher at home — .371 to .291.

“No wonder opposing pitchers were hammered all over the lot in Philadelphia, while on the road the Philadelphians couldn’t hit a balloon,” Dodgers manager Ned Hanlon said after the plot’s exposure.

Then as now, everyone stole signs, even the saintly Connie Mack. Many believed that was the reason Mack’s Philadelphia A’s beat the favored New York Giants in the 1911 World Series.

But, as Giants star Christy Mathewson pointed out, the A”s “stole honestly,” with their eyes.

That wasn’t how the 1900 Phillies worked.

According to a 1991 article by Joe Dittmar in the Society for American Baseball Research’s journal, the Phillies’ plot likely was born in the devious minds of backup catcher Morgan Murphy and Pearce Chiles, a journeyman infielder who also coached third base.

Murphy played 11 seasons but compiled a composite batting average of just .225. Chiles was 33 when his brief big-league career began in 1899. Three years later he’d be in prison.

Murphy was a top-notch sign thief, and Chiles loved a good scam. At some point, maybe as early as 1899, Murphy, who seldom started, began sitting in center field, where the lockers and offices were located at the Philadelphia Baseball Park, the Broad and Lehigh stadium later renamed Baker Bowl.

Hidden wires ran from his vantage point to a battery-powered device buried beneath the third-base box. If, for example, Murphy saw a fastball coming, he buzzed once, if a breaking ball, twice. Chiles, standing atop the box, got the corresponding electronic shock and relayed the info.

By late in 1900, opponents wondered why Chiles twitched so noticeably. One Philadelphia writer, tongue probably in cheek, suggested he suffered from “St. Vitus Dance.” It wasn’t long before someone figured it out.

When he came to bat in the third inning of Game 1 of a Reds-Phils doubleheader on Sept. 1, Cincinnati captain Tommy Corcoran strode down to the coach’s box and began digging in the dirt with his cleat.

The Phillies groundskeeper, aware of the submerged signaler, ran out to stop him. Both benches emptied. Home plate umpire Tommy Hurst hustled down the line. Ballpark police moved in.

Corcoran managed to unearth the box and showed it to Hurst. But rather than declare a forfeit or eject anyone, the umpire signaled that the game continue.

“Back to the mines, men” he shouted.

Talk of the plot and calls for penalties echoed throughout baseball.

“Someone should be severely censured,” said Dodgers treasurer Fred Abell.

The Phillies never were, and they apparently felt emboldened. That Sept. 26 in Brooklyn, Hanlon accused them of stealing signs. Murphy, he said, was positioned on an upper floor of a building just beyond Ebbets Field’s center-field wall. He was equipped with “a $75 eyeglass … so powerful it can see an eyelash at 250 yards.” Phillies batters were signaled by a waving newspaper.

Shettsline mocked the charges, noting wryly that Hanlon had gotten it all wrong, including the price of the eyeglass.

“It cost $65,” said the Phillies manager.

It wasn’t until Oct. 2 that Phils owner William Rogers addressed the matter. The long delay didn’t make his story any more plausible.

“It never existed,” he said dismissively of the Baker Bowl sign-stealing plot. “It’s absolutely too silly to discuss.”

The subterranean electronic device, Rogers insisted, had been part of a lighting system installed by a visiting circus earlier that season. It was never removed and when the Phillies stumbled on it, he said, they kept it there as a joke.

“A joke,” wrote a skeptical Inquirer sportswriter. “Neither Artemus Ward nor Mark Twain in his happiest moment ever perpetrated anything so deliciously humorous as that.”

The negative publicity prodded baseball officials to crack down on technology-based cheating. But it eventually would resurface, most famously with the 1951 Giants and Bobby Thomson’s Shot Heard 'Round the World.

Murphy retired after getting into just nine games in 1901. Chiles, meanwhile, never played again.

In 1902, Chiles was arrested for his role in a flimflam scheme and imprisoned in Huntsville, Texas. He escaped, but shortly afterward, following an assault, he was back in jail. He disappeared after his release and was never heard from again.

Chiles’ big-league highlight might have come the day after the box was dug out from beneath his feet. Sometime before the Sept. 2 game, he interred something beneath the first-base coach’s box. When the Reds detected it they dug it up only to find it was just a piece of wood with nothing attached.

Chiles and his teammates laughed uproariously.

“He was run out of Kansas and Texas years ago for serious crimes,” an El Paso columnist wrote after Chiles’ 1902 arrest. “How this man ever got on the Philadelphia team is a mystery.”