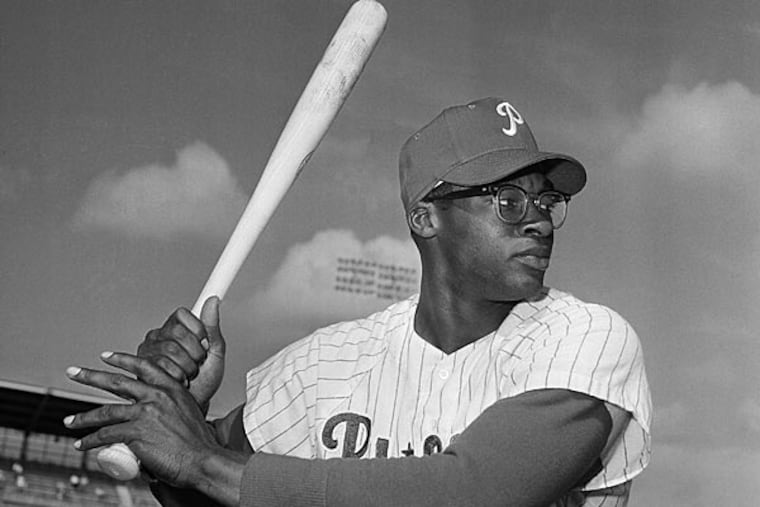

With Phillies set to retire Dick Allen’s No. 15, former teammates want the Hall of Fame to honor him this year, too

Allen, 78, would have been considered this fall for election by the Hall of Fame's Golden Days Era Committee. Now, he's going to have to wait until the fall of 2021.

It’s a week for Dick Allen stories, and Larry Christenson came armed with his best.

The scene: Sept. 5, 1976. Shea Stadium, New York. Christenson, scheduled to pitch for the Phillies against the Mets, breaks two 36-inch, 36-ounce bats in a rough round of batting practice.

“The only guy I could think of that uses a big bat like I do was Dick Allen,” Christenson recalled by phone the other day. “I walk up to him – I think he’s cupping a cigarette in one hand – and he’s got his glove over his bat handle. I remember saying, ‘Dick, can I use your bat during the game?’ He sticks the [40-ounce] bat out to me and he said, ‘Son, if you can swing it, you can use it.’

“And then the first time up I hit a home run off Mickey Lolich.”

Christenson lets out a hearty laugh. He retells the story often, and it’s a good bet it comes up again Thursday when the Phillies retire Allen’s No. 15 – 43 years after his final game and 57 years to the day of his major-league debut – in a pregame ceremony at Citizens Bank Park.

Why did it take so long to honor a player who hit 204 home runs in eight seasons with the team and has the highest slugging percentage (.530) of any right-handed hitter in franchise history? And why do it now, during a fan-less season in the midst of a pandemic?

The answer gets to the heart of why Christenson and many of Allen’s former teammates are disappointed with the recent decision by the Hall of Fame to postpone its Golden Days Committee election until next fall.

Allen, 78, wasn’t elected to the Hall of Fame by sportswriters and fell one vote shy in 2014 with the old Golden Era Committee, which was due to meet this fall as the Golden Days Era Committee. By finally retiring his number, the Phillies – managing partner John Middleton, former team chairman Bill Giles, and others who pushed to take No. 15 out of circulation – were sending an overt message that Allen’s enshrinement in Cooperstown, N.Y., is equally overdue.

But the Hall of Fame announced on Aug. 24 that the committee meeting would be pushed off because of COVID-19. Never mind that businesses across the country have conducted meetings virtually since March. The Hall’s committee process “requires an open, yet confidential conversation and an in-person dialogue involving the members of the 16-person voting committee,” according to Hall of Fame chairman Jane Forbes Clark.

“Personally I wish they would’ve done it this year, whether it be on Zoom or however,” former shortstop Larry Bowa said. “I think everybody thinks Dick’s going to get in eventually. But when you get a certain age, you don’t know what’s going to happen. At Dick’s age, you’d like to see it sooner rather than later.”

Christenson theorized that the Hall of Fame wants to limit the size of the 2021 class after the four-person 2020 induction ceremony was postponed.

“It’s just unfair because it’s something that was planned,” Christenson said. “It’s a shame. That’s the one real downfall of this whole celebration of finally getting Dick his due. Dick deserves the Hall of Fame. He deserves to have his number retired, and he needs to be celebrated in Philadelphia.”

Allen’s legacy is complicated. He was rookie of the year in 1964, American League MVP in 1972, and a seven-time all-star in 15 seasons. He hit 351 home runs. And as Phillies manager Joe Girardi noted on Wednesday, Allen had more offensive WAR (68.5) from 1964 to 1974 than Hank Aaron, Joe Morgan, and Carl Yastrzemski.

“We all know how good those guys are, and they’re all Hall of Famers, and rightfully so,” Girardi said. “But for 10 years, Dick Allen was a pretty dominant player. He’s a Hall of Famer for me.”

Allen also faced racism and discrimination in the 1960s en route to becoming the Phillies’ first Black star. He clashed with the media. Most fans didn’t take his side after a fight with teammate Frank Thomas in 1965. And his relationship with management and the fans soured so that he demanded a trade.

Christenson and Bowa, who played with Allen after the Phillies reacquired him in 1975, came to know him as a supportive teammate and a quiet leader. Christenson recalled Allen inviting him to lunch on the road and sharing walks to the ballpark; Bowa remembered Allen giving hitting tips in the dugout.

“He just had a great baseball mind. I don’t think people got to realize that,” Bowa said. “I don’t know what transpired with the media here. But you read stuff and get a chance to meet the guy, he was a good teammate and very knowledgeable about the game.”

Said Christenson: “I did know that there was controversy, and there was a lot of ways he was mistreated that didn’t sit well with me. You knew that was still hurting him inside. He was a great player, and should’ve been so much more appreciated. He was one of my favorite teammates of all-time. He was good to me.”

Christenson’s story from that Sunday in New York gets better. He hit a second home run with Allen’s bat (Allen finished 0-for-4) and went 8⅓ innings in a 3-1 victory.

Years later, Christenson asked Allen to sign a bat – not the bat – as a memento.

“It says, ‘To L.C., two homers with my bat. How about that? Dick Allen,’” Christenson said. “That was probably one of my highlights of my career.”

Maybe someday it can be told during an induction ceremony at the Hall of Fame.