Ubiñas: At Jewish cemetery, hoping family gravestones were spared

“We have to stop kidding ourselves,” he said as we stood among the broken stones. “Something bad is happening in our country.”

It had been a while since Judi Pogachefsky had visited the family cemetery, she conceded. Too long, she said. She had an idea of where the graves were, but she wasn't certain.

She walked slowly Monday morning toward Mount Carmel Cemetery, planted her wooden cane firmly on the top step at the front iron gate, and stepped down. She had driven down to Wissinoming from Bensalem to search for the headstones of her relatives: great-grandparents who died long before she was born, and a grandmother she lovingly called MomMom.

Pogachefsky wasn't supposed to be walking, not with her bad back. But she had to come, she said.

>>Click here for complete coverage of vandalism at the cemetery

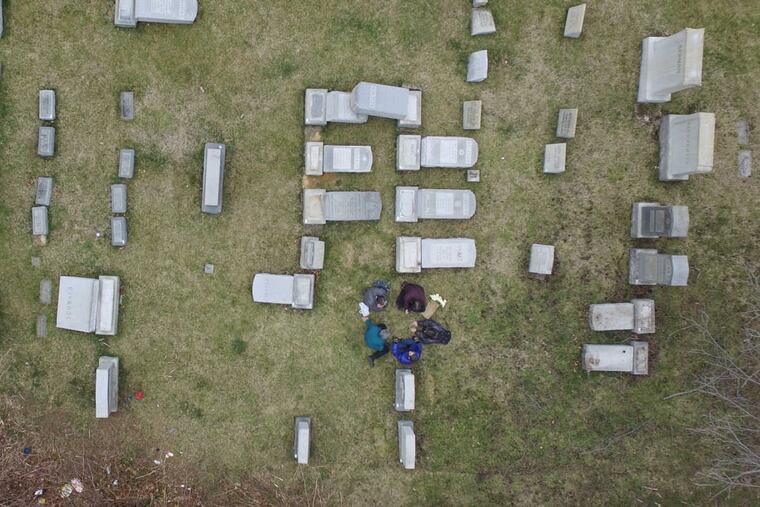

The 56-year-old woman hoped that their gravestones weren't among the 100 or so that were overturned and damaged at the Jewish cemetery in Northeast Philadelphia on Saturday night.

She approached the cemetery administrator, Richard Levy, and asked if he could help. He couldn't. He was there to survey the damage and to tell well-intentioned people that it was dangerous to lift the fallen tombstones.

Even if they stood them back up, they wouldn't stay that way if they weren't repaired properly, he told a group of Muslim men from the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community USA.

They understood, they just wanted to help any way they could.

"We need to be here for our Jewish brothers and sisters," said Salaam Bhatti.

I wanted to help, too, and just bearing witness didn't seem enough.

I'll walk with you, I told Pogachefsky. She could look for the stones closer to the paved road that ran through the middle of the cemetery. I could wander inside, where deep divots in the ground and toppled stones made it harder to maneuver.

All morning, people had been trickling in. When I arrived around 8 a.m., Steve Chesin was already there. The retired pharmacist didn't have family buried there, but like so many others, he felt compelled to come.

"We have to stop kidding ourselves," he said as we stood among the broken stones. "Something bad is happening in our country."

The vandalism comes a week after a similar incident in St. Louis. On Monday, several Jewish centers in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware were evacuated amid a series of bomb threats to Jewish institutions nationwide.

Many who came after Chesin echoed his fears. Hate and ignorance had taken hold, they said, and many put the blame and responsibility squarely on President Trump.

"The rabbis told us to vote for him," he said. "I voted for Trump and I'm waiting for him to do something about this. He needs to say something. He needs to do something. He's the president now." Trump did speak out last week after more than 170 Jewish tombstones were toppled in Missouri.

Pogachefsky didn't talk politics as we walked. She was too busy inspecting the headstones, afraid she'd miss one if she got distracted.

She found her great-grandparents' stone quickly. Samuel and Anna Adelman, it read. Samuel died at 46, from the same heart trouble that plague all the men in the family. Anna lived to 66.

Pogachefsky recalled that her grandparents and an aunt were somewhere close by, but she couldn't find them. So we walked deeper into the cemetery.

"What if I can't find them because their stones were knocked over?" she wondered, choking up. The stones were too heavy to turn over and check.

After about a half-hour, I could see that she was struggling to walk. I offered to escort her out but she said she wasn't leaving until she found her family.

I took her number so I could check back in later to see if she did.

On my way out, I took one more look, and there they were.

As I ran to her, I could see that she had stopped.

"Are they OK?" she asked, crying.

They were. She cried some more, and then she leaned on her cane and we walked toward them together.

"I'm so happy," she said. "I can go home and tell everyone that they're OK." She cried as she stood by the headstone of her grandmother.

Hilda Anne Adelman died at 94 in 2001. Her stone, which stood upright among so many ruins, read: Beloved wife, mother, grandmother and great-grandmother.

"We are so lucky," she said, hugging me. "Thank you."

I couldn't help but be happy for her, and for the family she was contacting as I walked away.

Until her words hit me.

Is that what we've come to, I wondered as I passed one toppled headstone after another? Lucky? Lucky when we aren't the ones being targeted?