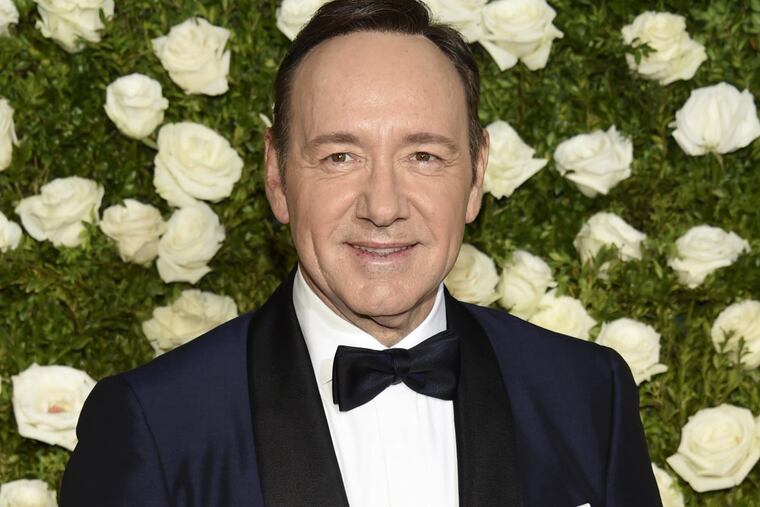

Why a noose is not just a noose, and why there's no excuse for Kevin Spacey's bad behavior | Kevin Riordan

The actor used his acknowledgement of sexual abuse allegations as a platform for coming out. But that's far from the most important part of the story.

Outrage over Kevin Spacey's response that he tried to force himself sexually on a 14-year-old boy in 1986 got me thinking about my own reaction to other sorts of controversies.

The social media uproar over a noose that was used as a prop during a Deptford restaurant's Halloween festivities struck me at first as much ado about not so much.

But I'm not black.

And my initial reaction to the tweetstorm last week about SJ Magazine's all-male women's empowerment panel was: This has got to be a joke.

But I'm not a woman.

I'm a white male. To me, a noose is merely a noose — not a bloodcurdling symbol of racist violence.

I'm a white male baby boomer who grew up never being excluded or judged based on gender or race. Guys who look like me have been in charge of pretty much everything as long I've been alive.

But because I'm a white male baby boomer who also is gay, I've had glimpses of what it's like to be told by members of the majority, either implicitly or explicitly, that what I think, feel, believe, or say is marginal, inconsequential, questionable, or even laughable.

I'm painfully aware that many still see the LGBTQ community's hard-won place at the big table as provisional, conditional, or less worthy than their own.

And while I will never know what it's like to move through the world as a woman, a person of color, an immigrant, or someone for whom English is a second language, I do know something about being addressed, assessed, or dismissed through a lens so narrow and arbitrary that it leaves viewers blind to anything other than their preconceived notions.

Which brings me back to Spacey.

To be clear: What the House of Cards actor is alleged to have done to Anthony Rapp — when the younger actor was barely out of middle school and Spacey was 26 — was wrong in every conceivable way, including morally and legally.

There is no excuse for a grown man to attempt the seduction of a child. Being so utterly intoxicated as to have no memory of what happened, as Spacey said may have been the case, is nowhere near exculpatory.

Spacey's semi-confession on Twitter followed a Buzzfeed story about Rapp's allegation, and it sparked even more anger for having been used as a coming-out platform, too.

Shades of former New Jersey Gov. Jim McGreevey's "I am a gay American" declaration of 2004, which looked to many like an intentional distraction from the corruption scandal that forced him to simultaneously announce his resignation.

I remember watching McGreevey on newsroom TV and giving him credit for acknowledging an essential fact about himself. I know a thing or two about how difficult that can be — and how liberating is the freedom that results.

I felt similarly about the portion of Spacey's statement in which he said he has now "chosen to live as a gay man."

Here yet again was more, and more politically useful, proof that the closet is a toxic and suffocating place that can twist the soul.

But I didn't "choose" to be gay.

I don't believe any of us do.

And I'm not a child sex-abuse victim.

I've never been exploited by an adult in authority, as Rapp described happened to him in Spacey's Manhattan apartment. Or as my colleague Maria Panaritis described in her masterful story Sunday about a predatory Philadelphia priest and the ruined lives he left behind.

So amid the wave of sexual harassment allegations against Harvey Weinstein and many other powerful men, most of them white and heterosexual, I must remember to listen not to myself ("Isn't some of this a bit … much?") but, rather, to the eyewitness accounts of those who were there. Like the accounts offered by Rapp and the survivors Panaritis interviewed — the testimony of those still carrying the scars.

It's especially important for me to do this, because as a gay baby boomer I remember what it's like to have my voice go unheard or ignored.

I'm old enough to recall when the few who spoke publicly about homosexuality, in the media and elsewhere, generally were straight "experts" from psychiatry, law enforcement, and the clergy, many if not most of them armed with agendas. Homos were perhaps to be pitied but preferably to be locked away.

So when black people react strongly to a racist symbol at a costume party, or women criticize a flier for a female-themed event that has only male speakers, or an actor describes being sexually harassed, I need to do the right thing. I need to listen.